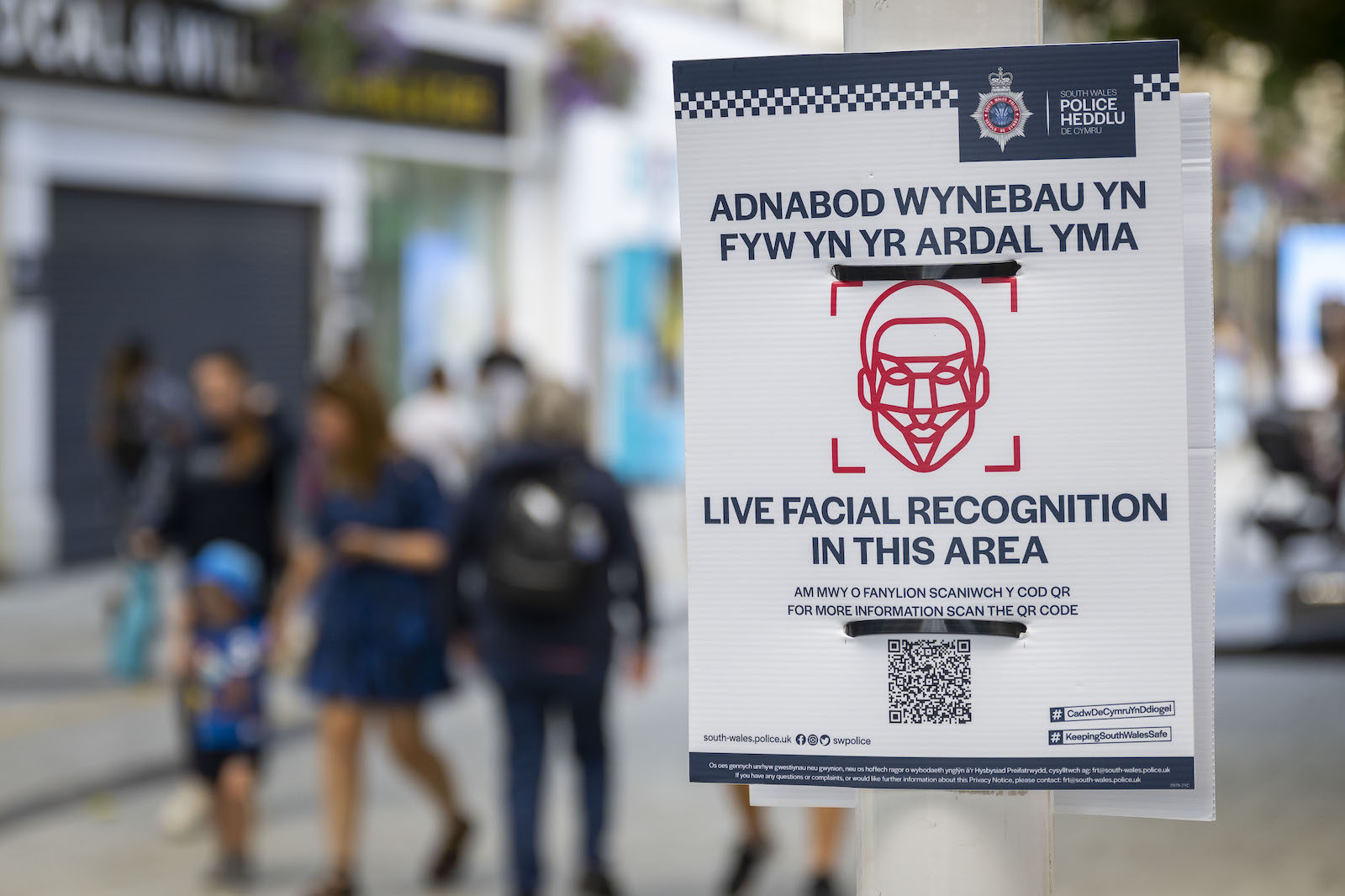

A sign on Queen Street in Cardiff city centre warning that facial recognition is being used by South Wales Police on August 25, 2022 in Cardiff, United Kingdom.

Photo: Matthew Horwood/Getty Images

A growing community of AI ethicists is helping companies to develop codes of conduct on the use of AI in their business operations. Charles Radclyffe is the CEO of EthicsGrade Limited, an AI governance-focused ESG ratings agency. As part of our ongoing series looking at different aspects of using AI in the workplace, we spoke to him about why AI should be treated as an ESG issue.

RADCLYFFE: Framing this issue in terms of ESG is useful because ESG is all about non-balance sheet risks and liabilities that organizations face and thus investors are exposed to. And just like any balance sheet where there are assets and liabilities, an AI system is potentially an asset for an organization — but equally can be a liability.

So AI governance very much falls into the ESG area. There are other people who are focused on climate risks or decarbonization or biodiversity. I just happen to focus on a very different niche of ESG, which not many other people cover.

The business community doesn’t like using the word “ethics.” We’d rather use a synonym such as sustainability, but really, what we are talking about is ethics, as I’m trying to bring light to the question of how well-aligned organizations are to their stakeholders’ values — and how well they are executing on what they are saying is important.

BRINK: In your experience, how reflective are most companies about the ethical side of AI governance or are they just looking at the business opportunity that AI represents?

RADCLYFFE: I would say we are getting close to a tipping-point, where this is moving from a sideline activity to becoming something which is very much forefront; but we’re not quite there yet. Ten years ago, no one cared at all about the risks. It was all about how we can use this capability to do the things that people do today, but a lot faster, and how we can put data sets together in order to extract value that they wouldn’t have had by themselves.

A single code of conduct is not particularly helpful. And that’s usually where organizations start to get themselves into that, what I would call, ethics-washing territory.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal was the “hole in the ozone layer” moment when ordinary people suddenly became aware of the darker side of these technologies but didn’t really start to change their behaviors. That is still an event yet to happen, but what we are starting to see now, certainly within the EU, is a lot more regulation being proposed around the tech industry.

You Don’t Need to Understand AI to Achieve Good Behavior

BRINK: In order to be able to implement an ethical code of conduct, do you need to understand the technology itself? Might that become increasingly difficult to do?

RADCLYFFE: No, I don’t think it’s necessary at all. One of the interesting things about the draft EU regulations on AI is that they make an attempt to define AI, but in very, very broad terms. That was deeply unsatisfactory to most members of the technical community because it was so broad and so vague.

The European Commissioners are insisting that AI systems in the EU are developed with two things in place: firstly, a risk management process; so an organization needs to understand whether the use of AI in its own domain is high risk or otherwise. And if it is high risk, then it needs to be a minimum standard of conformity to what the EU defines in its call for quality management.

And a company has to put those quality management controls in place not only around its own technologies, but also build that into its supplier relationships and procurements. And that’s something which we haven’t really seen around the use of technology up until now.

At the end of the day, having good risk management controls and good quality management processes should be something that responsible organizations should strive for whether they are using AI, quantum computing, other tech magic, or just simply using Excel or paper tools. I don’t think the definitional issue of what AI is or AI is not is particularly relevant here.

BRINK: But to build an effective risk management tool, you need to understand the risks that AI could generate. Since we don’t know why a computer does something, it is difficult to predict how it’ll behave.

RADCLYFFE: That’s very true. The Commission does make this easier by defining certain categories of activity which will always be high risk. So for example, if you’re involved in the credit decision-making process around an individual, or the use of AI in HR systems, such as what will be regulated in New York City from January 2023 — but what the regulators are looking at is: have you thought through what is particularly high risk, medium risk, low risk for your organization and for the areas that you deem to be high risk — does that trigger the requirements of the act?

The trap that a lot of organizations fall into is that they end up trying to create a set of rules or principles that apply to the whole organization and particularly to engineers building this stuff. And then lo and behold, the engineers don’t quite get it right. And when it hits their headlines, it’s deeply embarrassing for the firm.

We can borrow a lot of best practices from the ESG community. One of the key things in relation to ESG discipline is around how an organization engages with stakeholders — how well it identifies who its stakeholders are — secondly, how well it understands what those stakeholders care most about. And then thirdly, how it manages the tension points and conflicts between those needs.

BRINK: Is there enough commonality across different industries and ways of using AI to have a common code of conduct?

RADCLYFFE: I think a single code of conduct is not particularly helpful. And that’s usually where organizations start to get themselves into that, what I would call, ethics-washing territory.

What they need to do instead is identify who its stakeholders are. And then find a way of identifying what each of those stakeholder groups cares most about. And then looking for the tension points between those things and designing strategies to address those tensions.

Let me give you an example.

You want to introduce facial recognition, as a hypothetical example, in order to help people enter the office premises in a zero-contact way. So rather than having a swipe card to get into the office in the morning, you just have a camera and the camera keeps the barrier open, and it recognizes your face.

In a place like China, for example, no one would flinch at such a system, but in Germany, you can imagine you’d have a lot of controversy around that. What you need to do in that situation is to be able to talk about the use of AI, identify which stakeholders would be affected by it, hear their concerns, and articulate your response. And it may be that an international organization might say, we’re just not going to do this for these reasons (and very much should articulate the why alongside its decision).

Then another situation comes along where they might want to use facial recognition systems in order to secure the perimeter of their factories. And because it’s a different use-case, it might be deemed that actually those security concerns are more important than stakeholder privacy concerns, and therefore, for the use case of security, it’s acceptable. But for the use case of allowing employees into the building from a convenience perspective, it’s not. Again, the decision and the rationale should be articulated.

Now you’ve got two examples, which is very, very helpful for engineers to triangulate a third, fourth, fifth example as to which side of alignment falls. Humans are really good at filling in the blanks – we’re just not so good at explaining whether we’ve achieved fairness or justice and are much more likely to twist and turn definitions if you apply the principles-based approach.

And you don’t need many of these use cases. Five or 10 well thought-out examples are perfectly fine for an engineering team to use that case law, as it were, in order to take any other use case and to deem how best to govern it.