ASEAN’s Impending Demographic Troubles

Workers enjoy their lunch break in Singapore's financial business district. Most ASEAN countries face declines in labor supply growth.

Photo: Roslan Rahman/AFP/Getty Images

Most Asian economies have yet to confront the impact of demographic headwinds on growth of the labor force and the economy—and none more so than Singapore, where the problem is expected to be particularly pronounced.

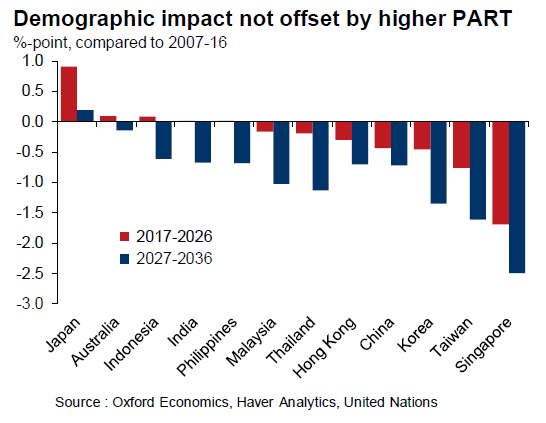

Our analysis finds that policy measures to boost labor participation rates limit the impact of the region’s larger demographic trend on labor supply growth, but they typically cannot fully offset it. As a result, we think almost all of the region’s economies will experience declines in labor supply growth in the next two decades, and this can have significant implications on the region’s economic prospects.

While Japan still continues to be talked of as the country caught in a demographic tangle, the reality is that, going forward, the adverse impacts of an aging demographic are going to be felt more strongly in economies like Korea, Taiwan and the ASEAN economies such as Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia.

Demographic Headwinds

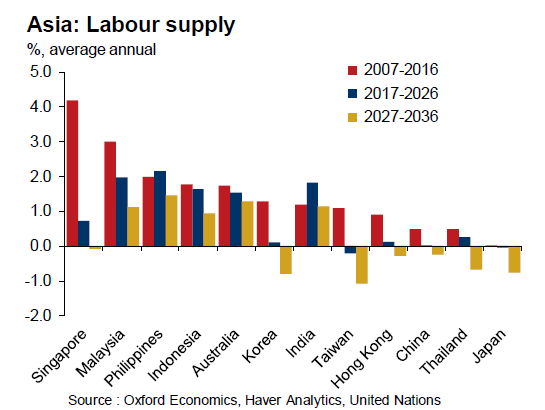

Many ASEAN economies are experiencing demographic changes that imply downward pressure on labor supply and economic growth. Our forecasts on demographics and labor participation help gauge how much economic growth will come under pressure. We are particularly interested in assessing the extent to which things will worsen. To do so, we look at how the demographic evolution and changes in labor participation will affect labor supply growth in the next 20 years, compared to the recent past (2007-2016). We find that, while there is wide variation, most economies will experience declines in labor supply growth, in spite of rising labor participation rates.

For some Asian economies, the demographic transition is nothing new. Between 2007-2016, Japan’s working-age population (15-64) declined by an average 0.9 percent per year. It only grew by 0.4-0.6 percent in China, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong after much faster growth in earlier decades. These economies have already felt the impact of demographic changes and adjusted and responded to them to varying degrees.

We think almost all of ASEAN’s economies will experience declines in labor supply growth in the next two decades.

However, most ASEAN countries are only now beginning to feel the effects of the demographic transition.

Will it Worsen in the Coming Decades?

While the general trend in working-age population is toward slower or even negative growth, the extent varies strongly across Asia. In Japan, we now expect no significant further reduction in working-age population growth; and in Australia, we see it continuing to expand by around 1.5 percent in the coming two decades.

But on the other hand, we expect a massive decline in Singapore’s working-age population growth, in part because of less immigration after a recent policy shift.

Malaysia will also face a large deceleration, while South Korea, Taiwan, China, Thailand and Hong Kong will see growth turn negative.

Many governments have taken measures to boost the labor participation rate (PART)—the proportion of the labor force (people who would like to work) to working-age population—to mitigate the demographic pressures. The labor supply forecasts on our Global Economic Model incorporate our estimates of the impact of government policy and other factors on labor participation through 2036.

Exhibit 1

Lessons from the Japanese Experience

In Japan, labor market reforms have already raised participation substantially, especially by drawing more women into the labor force, and we expect this to continue in the coming years. As a result, we forecast the labor force to remain unchanged in 2017-2026, even as the working-age population shrinks by 0.7 percent per year. However, as there are limits to how much various groups’ participation rates can rise, we project the overall Japanese labor force to fall by an average of 0.8 percent per year in 2027-2036.

One caveat is that new groups drawn into the labor force, such as women and senior citizens, tend to work fewer hours compared with other groups. This is one reason why the total number of hours worked often does not rise proportionally with increases in the labor force. In Japan, the total number of hours worked has actually fallen since 2012, despite a substantial increase in employment.

Nonetheless, just as rising participation is a rational first response to the demographic transition, it is possible that increases in the number of hours worked for certain groups will be another response later on.

We also expect participation rates to rise significantly in ASEAN economies such as Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines, largely because of policy changes.

Labor Force Growth

While Japan’s economic growth has already been hit by demographic headwinds in recent decades, we expect the impact on (the change in) labor force growth to ease somewhat in the coming decades. Because of rising labor participation, we expect the net impact on labor force growth to be positive compared with the starting position of already large declines in the working-age population in 2007-2016. But in 2027-2036, when there will be limited room for further increases in Japan’s labor participation, the labor force will decline by an average of 0.8 percent per year.

In Australia, relatively high birth rates and immigration minimize the impact of demographics on the growth in labor supply; we forecast it to average 1.3 percent per year in 2027-2036. In Indonesia, India and the Philippines, we expect the impact of rising participation to also offset the deceleration of the working-age population in 2017-2026. However, we expect the latter to dominate in 2027-2036, resulting in a significantly negative impact on labor supply growth, compared with the starting position in 2007-2016.

In the other major Asian economies—Malaysia, Thailand, Hong Kong, China, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore—the net impact on labor force growth is negative from 2017-2026 onwards. In Malaysia, Hong Kong and China it remains contained to less than 0.4 percentage points in 2017-2026 and less 1 percentage point per year in 2027-2036. But we expect the net impact in Thailand to reach 1.1 percentage points per year in 2027-2036, leading to an expected average decline in the labor force of 0.7 percent.

Exhibit 2

The worst affected economies are South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, with a negative net impact on labor supply growth of between 1.4 percentage points annually in South Korea and 2.5 percentage points in Singapore in 2027-2036, compared with 2007-2016. As shown in Exhibit 1, we expect Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand to all see significant declines in labor supply in 2027-2036. But, unlike for Japan, this constitutes a large negative shift for South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore (Exhibit 2).

Impact on Economic Growth

Our projections can be used to provide an indication of how much economic growth will come under pressure in Asia in the coming decades. Our model’s production functions suggest that 1 percentage point less labor force growth means a fall in GDP growth of 0.5-0.67 percentage points.

Given its impact on economic growth and prosperity, the demographic challenge looming on the horizon can have serious consequences for the region. Asian economies better start preparing.