Implications of China’s Shrinking Current Account Surplus

A general view of the Beijing skyline. China’s current account surplus is expected to fall close to zero in 2018.

Photo: Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

This is the first story in a weeklong series on China.

China’s current account surplus is expected to fall close to zero in 2018, and it is only expected to rise marginally in the coming years. While it does not imply a watershed moment in terms of foreign exchange market mechanics and the balance of payments, the virtual disappearance of the current account surplus this year will affect views regarding financial stability, sentiment on the CNY, and the policy stance with regard to capital account opening.

Strong Domestic Demand in China

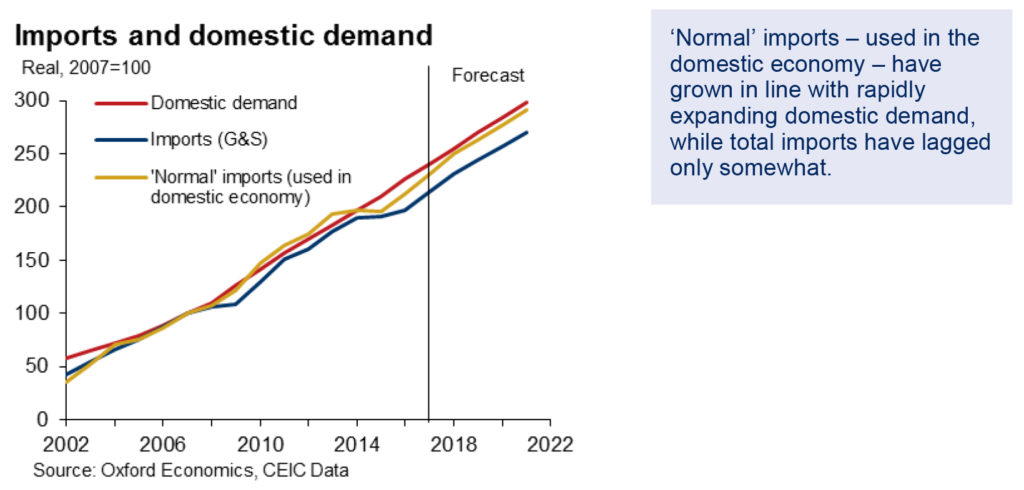

China is a relatively rapidly growing economy, and thus, its current account balance is subject to downward pressures. With domestic demand growing significantly faster than demand from its trading partners, imports tend to outpace exports, other things being equal. China’s real annual domestic demand growth averaged 9.2 percent in 2008-17, compared to a paltry 2.9 percent globally. China’s demand growth drove an average annual expansion of 8.9 percent of real “normal” imports. Overall, average annual real import growth was somewhat slower, at 8.1 percent, as the processing sector—where components are mostly imported, processed and re-exported—lagged behind “normal” external trade in the 2008-17 period.

China’s Export and Global Demand

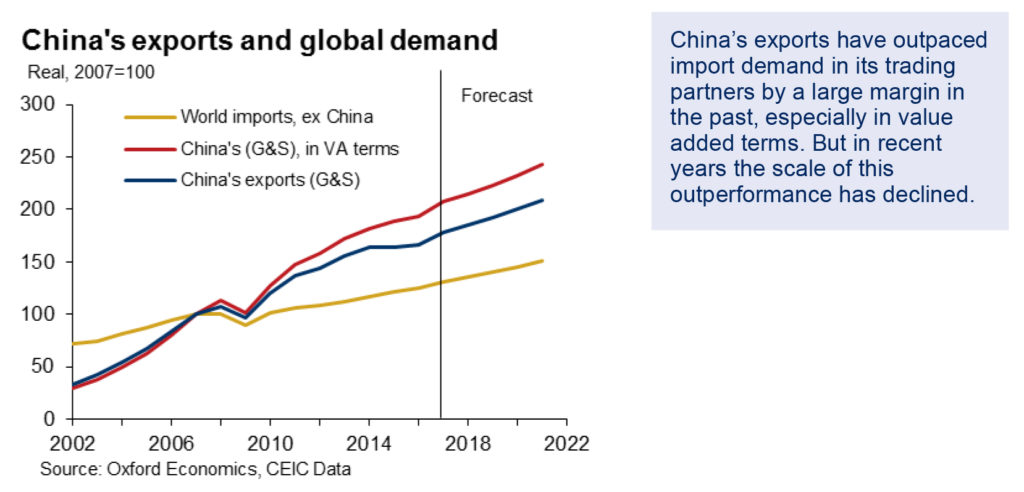

China has been able to offset much of this pressure, as its exporters registered massive gains in global market share—but these gains have diminished in recent years. In the five years prior to 2017, China’s exports outgrew global import demand (excluding China) by 0.8 percentage points on average in real terms, compared to 6.1 percentage points average outperformance in the five years through 2012. This was followed by a whopping 17.9 percentage points in the five years through 2007.

The close long-term correlation between imports and domestic demand hides the fact that various influences affecting imports have shown a tendency to offset each other. As China’s manufacturing sector moves up the value chain and increases its competitiveness, Chinese households and firms have sometimes switched from foreign brands to domestic ones. Examples are smartphones, household items and construction equipment.

In a similar vein, domestic manufacturers and foreign companies operating in China have increased their sourcing of components from within China rather than importing them. In the case of export-oriented manufacturing, this has meant that exports have risen faster in value-added terms than in headline, gross terms. However, these factors have been offset by increased interest in imported products and foreign brands as Chinese household incomes rise and tastes evolve. In addition, spending abroad by Chinese tourists has risen rapidly.

China’s terms of trade (the price of exports relative to that of imports) have fluctuated quite a bit since the early 2000s. But they have not trended up or down in a major way over long periods of time and do not alter the long-term trend of the current account balance significantly, though the rising oil price since mid-2017 has undermined the surplus.

In all, the current account surplus has fallen, as a share of GDP and in absolute terms, since it peaked at 9.9 percent of GDP in 2007. In 2017, it was only 1.3 percent of GDP. Looking ahead, the secular trend of China’s domestic demand growth outstripping that of its trading partners will remain a drag on the current account, even though we expect China’s domestic demand growth to cool down over time. Other factors will also weigh on the current account in the short term. The trade conflict with the U.S. will depress export growth, while China has this year lowered import tariffs on a range of goods, including cars, consumer goods and some capital goods, which will further support imports.

Forecast on Current Account

We forecast that the current account surplus virtually disappears this year and next. The baseline forecast includes a modest increase of the current account surplus in 2020 and 2021, because of the gradual slowdown in domestic demand growth and some import substitution due to China’s industry moving up the value chain. However, the balance of forces may play out differently, and it is also possible that China will run a modest current account deficit in the coming years. What are the consequences of this development in the current account?

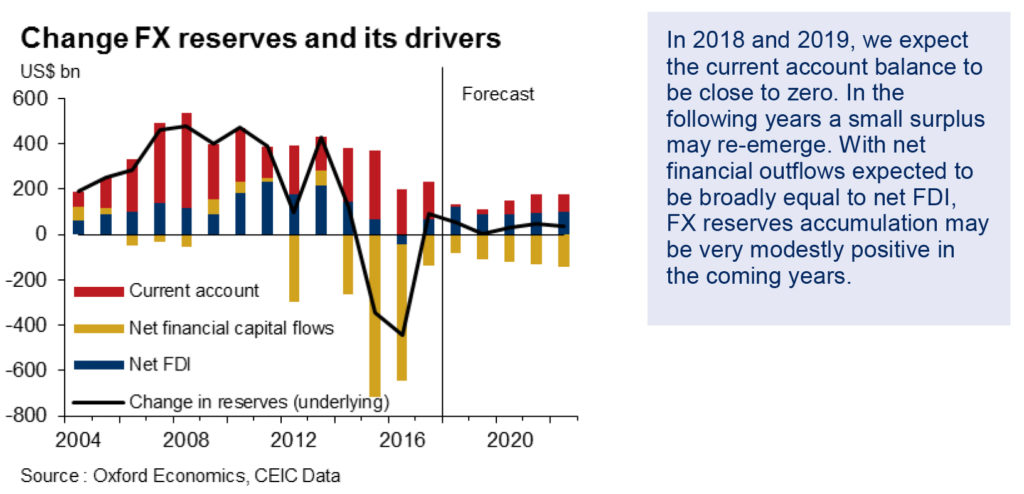

In terms of the mechanics of the FX market and the balance of payments, a decline in the current account position to around balance in 2018-19 does not constitute a watershed moment. It is expected that net financial capital outflows will broadly equal net FDI in the coming years, leading, overall, to low but still positive FX reserves accumulation if the current account stays in marginal surplus. The fact that this slight increase in FX reserves is forecast is not a coincidence but a function of what we think policymakers will likely aim at, with the policy stance on net financial outflows remaining as tight as it needs to be to keep reserves accumulation just about positive.

Reduction in the current account surplus will have a significant impact nonetheless. In recent years, as investors considered China’s financial stability risks, amid high and rising leverage, the traditionally large current account surplus has always been a source of comfort, as it implies that China does not need to attract capital from abroad to finance its growth. However, we expect minimal actual pressure on the FX market and the sentiment on China’s financial stability and the exchange rate to be affected negatively. With China’s productivity continuing to rise substantially faster than in its trading partners, its real effective exchange rate should strengthen further. However, trend REER appreciation will probably be more moderate than in the past, given the much smaller current account surplus.

Impact of Weaker Balance of Payments

A less strong balance of payments outlook will influence China’s policy toward capital account opening. We expect the policy stance on financial outflows to remain a function of the balance of payments situation. Thus, the shrinkage of the current account surplus will be a constraint on the policy stance with regard to capital opening in general and financial outflows in particular.

In all, the virtual disappearance of the current account surplus is not expected to lead to a major upheaval—it will have an impact on views regarding financial stability, CNY sentiment and the policy approach to capital account opening.