Can Trade Take Cambodia to Prosperity?

A ferry transport Cambodian people across the Mekong river in Phnom Penh on August 27, 2014. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has set 2015 as the target to create a single economic market across the 10-nation bloc that is home to some 600 million people.

Photo: Tang Chhin Sothy/AFP/Getty Images

This past summer, the World Bank officially upgraded Cambodia to a “lower middle income country,” a move that confirms the country’s upwards economic trajectory over the past 20 years.

But despite this new status, which Cambodia shares with 51 other economies including India, Vietnam and the Philippines, the country is still associated with darker images: landmines, civil war and the Khmer Rouge regime. At best, perhaps, it’s seen as a new frontier destination for investment and tourism.

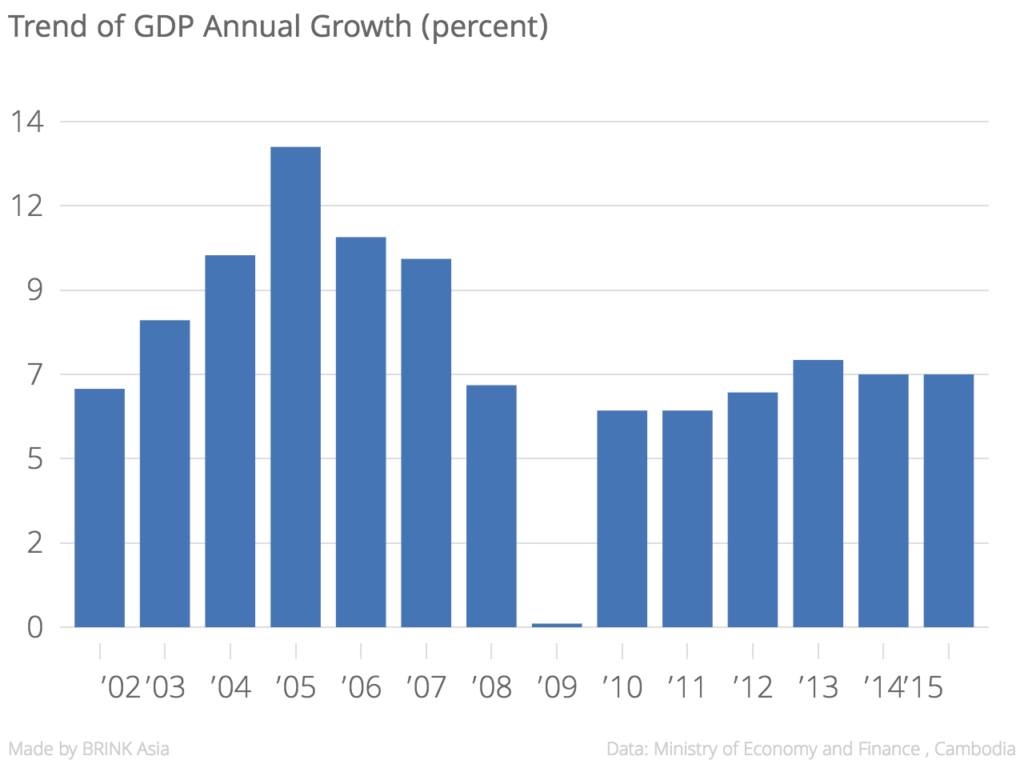

For development economists, though, this reclassification comes as no surprise: Cambodia’s economic development has earned it the title “olympian of growth” in some quarters, thanks to sustained double-digit growth between the years 1998 and 2015 (with the exception of 2009 and 2010, following the international financial crisis).

A Rapid, Sustained Rise

This rise is impressive not only for its rate, but also for its resilience. The country has been growing at a stable rate over time, making it the world’s sixth-fastest‑growing economy. While some would argue that its growth is “normal,” considering it started at lower level, the uniqueness of Cambodia’s growth lies in its continuity over 20 years.

Since 1950, only 13 economies in the world have grown at a rate above 7 percent per year for a quarter of a century or longer, and Cambodia is not an oil‑producing country. Its growth has been mostly driven by trade and by a buoyant demand for labor‑intensive manufacturing (textiles and clothing), a booming tourism industry, growth in construction and, to a lesser extent, an increase in agricultural exports. New opportunities within the Southeast Asian region have also emerged, fueled by deeper integration in the ASEAN economic bloc.

GDP per capita has increased, inflation has been kept under 5 percent and the poverty rate has declined from 53 percent in 2004 to 16 percent in 2013. Yet there’s a long way to go before Cambodia achieves its vision of becoming an upper‑middle‑income nation, meeting all the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 and turning into a developed country by 2050.

For this to happen, Cambodia will need to accelerate growth, diversify its relatively narrow economic base and enter regional and global supply chains. Only then will it satisfy the UN’s triple criteria for graduation from the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), which accounts for income, human assets and economic vulnerability, and join the only four countries that have managed to graduate so far: Botswana, Cabo Verde, Maldives and Samoa.

Cambodia has benefited from the strong support of development partners—both bilateral and multilateral—in jump‑starting its weak economy in the mid‑1990s, with the result that it is now widely perceived to be aid‑dependent. Total aid, including disbursements to non-governmental organizations (NGOs), amounted to around $12,108 billion between 1992 and 2011 in supporting sectors such as governance, agriculture, environment, education, healthcare, energy and transport.

While the development community has been generous with Cambodia, it has also closely monitored the use of aid resources. This has encouraged the Royal Government of Cambodia to adapt, initially unguided, to multiple rules, expectations and governance aspirations, always ensuring that resources flow to the most important and promising sectors.

A New Trade Route

Trade has been a big recipient of development support for the role it plays in achieving sustained growth and economic development. Cambodia has benefited from preferential market access offered by its main trading partners such as China, the EU, Japan, the U.S. and the ASEAN partners, but also from a steady and strong partnership with the Enhanced Integrated Framework (EIF), the only Aid for Trade program exclusively dedicated to the Least Developed Countries.

Since 2001, the EIF has supported Cambodia’s journey toward economic growth and poverty reduction through trade. It has contributed to building the national capacity to design and manage Aid for Trade programs, notably through the establishment of the sector-wide Approach on Trade, a key mechanism for coordination among the Cambodian government and development partners and for channelling Aid for Trade resources. It has also sponsored several far‑reaching trade diagnostics and helped Cambodia to diversify its economy and to move up the value chains in high export potential sectors, such as high‑value silk, milled rice, marine fish products and cassava products, as well as in the hospitality industry.

Development Growth a Risk in Itself?

Graduation from LDC status can be a double-edged sword for a country, because it entails the loss of preferential market access and a possible reduction of development aid. Like for the other recently graduated countries, the EIF will help Cambodia to ensure a smooth graduation, supporting the preparation and continuing its assistance for five years afterward.

In the long run, the success of the Cambodian economy will be driven by the nation’s entrepreneurs and the private sector and not by more international assistance, as reliance on aid is neither sustainable nor desirable in the long term. The recent reforms aimed at reducing the cost of trade, increasing competitiveness and implementing an industrial development policy are steps in the right direction.

For its vision to be realized, the Cambodian government is conscious that far‑reaching reforms are needed to make economic growth work for all. Only then can the perception of Cambodia change for good.

This piece first appeared on the World Economic Forum Agenda blog.