Gas and Power Politics in the Eastern Mediterranean

A crane vessel laying the platform for the Leviathan natural gas field in the Mediterranean Sea. Eastern Mediterranean fields are commercially unattractive even though they would allow Europe to diversify further away from imports of Russian pipeline gas.

Photo: Marc Israel Sellem/AFP via Getty Images

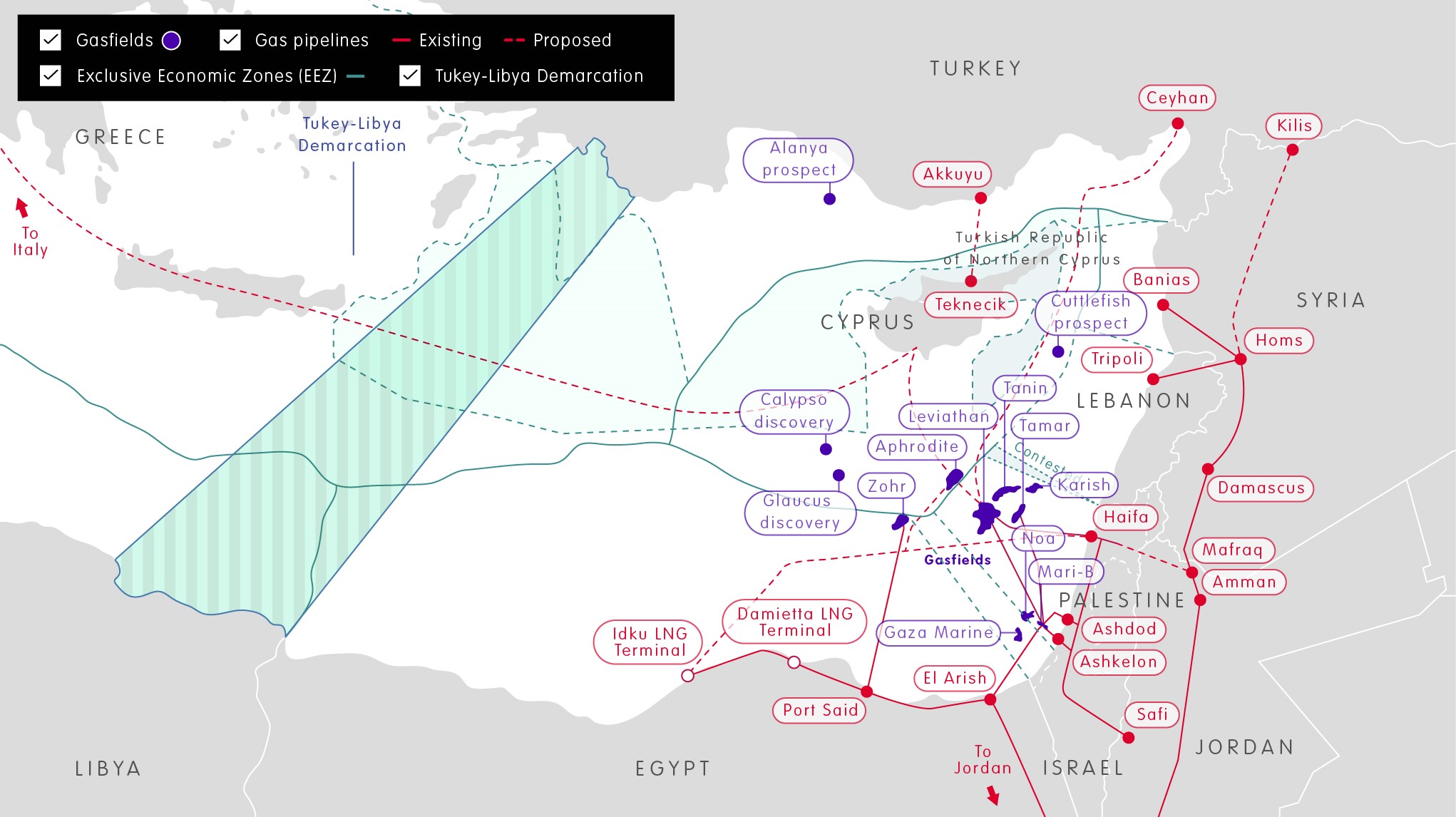

In recent months, tensions between Turkey and Greece have been increasing over disputed gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean. Although huge gas deposits have been discovered in the area, the decline in demand for natural gas due to the economic recession has led to questions over the fields’ viability.

BRINK spoke to John Bowlus, editor-in-chief of Energy Reporters and a researcher at the Center for Energy and Sustainable Development at Kadir Has University in Istanbul, about what lies behind this.

BOWLUS: Of course, there are many interconnected layers to this tension. The gas element is important to Greece, Turkey and Cyprus. But internationally, the gas fields there are not as important as they once were, so the international community has been largely ignoring the problem. More broadly, the United States has stepped back from the region over the last decade. Since Turkey and Greece are part of NATO, the U.S. needs to be actively involved in trying to sort out their differences.

But instead, we’ve seen this turn into a France-led EU standoff against Turkey largely driven by rivalry over Libya this summer, where Turkey has taken a strong position in the west, while France is a big backer of the Haftar-backed east in Libya.

Power Vacuums

The result is a more isolated Turkey that is responding with greater assertiveness. So, while the gas is important to Turkey and Greece, more broadly the tensions derive from competition to fill power vacuums in Libya, Syria and elsewhere.

In recent weeks, tensions have subsided. NATO has nurtured dialogue between Turkey and Greece and set up what’s called a bilateral military deconfliction mechanism, which includes a 24-hour hotline to mitigate the risk of a hot clash that could happen through some mishap at sea. We saw this in August.

In the end, no one wants any sort of armed conflict, and there seems to be genuine willingness on the part of all actors on this point.

BRINK: How did the latest gas dispute come about?

BOWLUS: The issue stems from differing claims of national sovereignty and revolves around the Greek islands and whether they are entitled to so-called exclusive economic zones (EEZs). Turkey and Greece disagree on the delimitation of maritime borders and thus EEZs. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) says that all countries, including islands, have 200-mile EEZs from their shorelines in which they can explore sub-sea resources or pursue other economic activities.

Greece is one of 167 signatories to UNCLOS, but Turkey is not (the U.S. and Israel also have not signed UNCLOS) and pushes back against the 200-mile EEZ contention. It has a point: Any objective observer who takes a casual look at the map would see that Greece’s 200-mile EEZs leaves Turkey with very little space, as the Greek Islands are so close to its shores.

The Gas Issue is Centered on Cyprus

The gas issue has now centered around Cyprus, about which the two countries have had problems before. Tensions regarding islands in the Aegean Sea helped lead to the 1974 conflict over Cyprus and the Turkish invasion in July. Today, they still don’t legally agree, but they agree to disagree and just get along in the Aegean.

But not in the eastern Mediterranean. Since Cyprus started finding gas in 2011, tensions have simmered. Turkey began engaging in brinkmanship in 2018 by sending naval vessels to harass the oil exploration ships of Western companies and then this summer raised the temperature even further.

Turkey wants to participate in the gas development, and based on national sovereignty claims, believes it has a claim to some kind of EEZ or in a partnership or condominium with Greece to develop Cypriot gas. Bringing Turkey into the development of these resources would solve the problem and would be similar to the agree-to-disagree stance on maritime borders in the Aegean.

BRINK: Where are the main gas deposits? It sounds like Greece and Cyprus hold most of them?

BOWLUS: Yes, that’s correct. There are several discoveries in Cypriot waters, but only the most recent Cuttlefish discovery lies in areas that Turkey disputes. The 2011 Aphrodite discovery is very close to Cyprus’s maritime border with Israel and had an American company, Noble Energy, developing it (Chevron just completed the purchase of Noble). Neither Aphrodite nor the others have gone into production.

Source: European Council on Foreign Relations, May 2020

Egypt has a lot of fields, including the supergiant Zohr field discovered in 2015. Israel has the Leviathan and Tamar fields that are already producing. So there is a distinct Israeli-Egyptian gas nexus — the two countries trade gas and collaborate on re-exporting it — while the rest of the eastern Mediterranean is on hold.

Commercially Unattractive at this Point

BRINK: The price of natural gas has obviously been dropping. So are these fields still sustainable?

BOWLUS: The international companies have all suspended further exploration and development of Cypriot fields until 2021 — which could extend longer. The global gas market is vastly oversupplied and, as you said, prices are low. There’s so much liquefied natural gas (LNG) coming onto the market from the U.S., Russia, Australia and elsewhere. Qatar, very importantly, is planning a big expansion that’s set to come online in 2025.

At the same time, there’s a decreasing amount of market share available for new gas. So in this regard, eastern Mediterranean fields are commercially unattractive even though they would allow Europe to diversify further away from imports of Russian pipeline gas. But there is just so much LNG from the U.S. and elsewhere to diversify that it’s no longer important.

The U.S. and Russia are both competing to supply Europe, and neither of them has any interest in seeing more eastern Mediterranean gas come onto the market to compete.

BRINK: Are we seeing any move away from LNG gas to renewables in the region?

BOWLUS: There are steps being taken towards increasing renewables throughout the region. Turkey touts that now 44% of its power generation capacity is renewable and 34% of its generation in 2019 was renewable. But Turkey and Greece still depend essentially 100% on imports for gas. Turkey paid $42 billion last year for energy imports — $12 billion of which was gas. So, for Turkey and Greece, the gas fields are important just to limit their import bills.

It’s very difficult to predict energy markets but I think it’s safe to say that gas has a decent future in the sense that, yes, there’s climate change, and gas is still a dirty fuel, but gas in Europe and in North America has played a large role in decreasing coal, which is a big reason why emissions have either flattened or are starting to decline in those areas. So, gas still remains attractive from an emissions standpoint.