How Supermarkets Can Take on Grocery’s Brave New World

Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods Market is an example of the kind of threat presented by high-quality players able to provide consumers an integrated online and in-store experience.

Photo: Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images

The traditional supermarket is under assault. After a half-century as the go-to destination for shoppers throughout the industrialized world, new business models are making the traditional supermarket less relevant. That’s a danger because supermarkets’ high overheads require correspondingly high sales volumes to maintain profitability.

To be relevant going forward, supermarkets need to find new ways to appeal to increasingly diversified consumer demands while simultaneously reducing costs.

Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods Market is an example of the kind of threat presented by high-quality players able to provide consumers an integrated online and in-store experience. This threat is taking place throughout the world, with Hema stores in China similarly leveraging owner Alibaba’s digital roots. Customers get product information by scanning the products with their smartphones, paying with Alipay, and receiving personalized recommendations based on their overall purchase histories. This approach is proving effective in fostering loyalty with digitally oriented consumers, and it generates information for Hema to create interesting new products.

From another direction, hard discounters are moving beyond their traditional role of providing consumers low prices and are adding a richer customer experience that includes a robust fresh-food offering. Longtime experience with producing private brands—one reason for their low prices—has honed their skills at running well-integrated supply chains where they can design, test and ship trendy items in every category. This lets them keep pace with fast-shifting consumer preferences, such as gluten-free and nongenetically modified foods.

Hard discounters, which operate in more than 20 countries, can also cross-pollinate the best of their internationally sourced products—Italian olive oil and pasta, German chocolate and sausage, and French wines—packing their stores with a tightly curated and interesting array of products.

The discounters have also engineered an easy-to-shop store model with low operating costs, positioning them to thrive in an era in which consumers split their spending across several different stores.

Hard discounters are expanding their presence around the world. Lidl this year joined fellow German discounter Aldi in the United States, both having announced aggressive five-year expansion plans.

Finding Ways to Fight Back

To fight back, supermarkets first need to find ways to lower costs so they can invest in remaining price-competitive and have the funds needed to finance new ways to connect to changing consumer demands.

One such approach is to take a serious look at their private-label strategies. In the past, private brands were seen—especially in the U.S.—as cheap alternatives to superior national brands. But European supermarkets and hard discounters have demonstrated that private brands can be a powerful tool for differentiating a store and providing a unique connection with their customers. They can thus become a significant contributor to the bottom line through the sales and customer loyalty they generate—and they can also give a store negotiating leverage with national brand manufacturers.

Chasing the Private Label

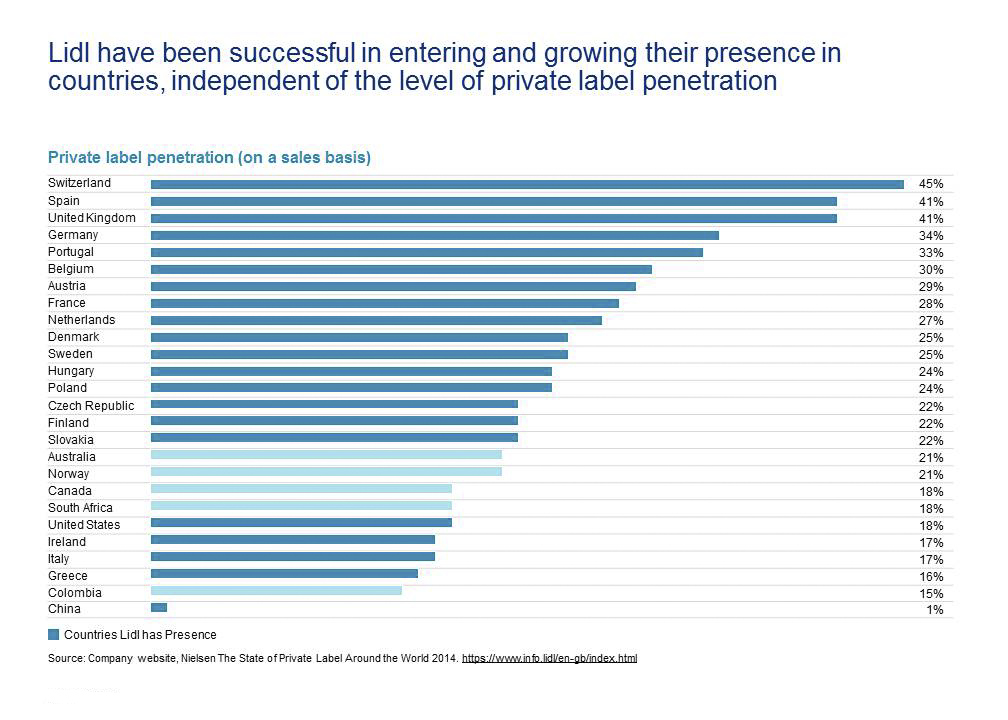

Private label market penetration varies by a factor of three across the countries shown (see chart below), with the U.S. placing near the bottom, indicating a consumer preference for well-advertised and recognized national and regional brands. Low private label sales could support the position “Americans don’t like private label products” or it could be flipped to suggest a massive upside for innovative private label products that connect with the emotional needs of American consumers, such as food origin, authenticity, story, wholesomeness, and earth friendliness.

Retailers are betting on the upside, as we are witnessing a private label modern day renaissance in North America. Various private label offerings are now in play in North America: stores dedicated to private labels (Aldi, Lidl and Trader Joe’s); major chains offering a premium and/or on-trend private label line (Loblaws, Costco, and Kroger); and in-store and online private brand presence, such as Whole Foods 365, available in-store and on Amazon. This improved availability of higher quality private labels will stimulate American buyer interest for trial and repeat purchase.

It would be convenient to look at the chart and interpret the U.S. as difficult soil for a company such as Lidl to take root. Yet in Ireland, Italy and Greece, all of which have low private brand penetration, Lidl’s sales per square foot are higher than in Lidl’s home country of Germany. High store efficiencies are not the only soil test that will certify success for private labels in the U.S., but it is a healthy indicator that retailers should continue to plow more private label crops.

Supermarkets need to recognize that now is a time of momentous change. The first step to dealing with it is to ask: Who do we want to be? And, How will we meet the needs of the fast-changing consumer?