Multi-Pronged Approach Required To Address Climate Risk in Australia

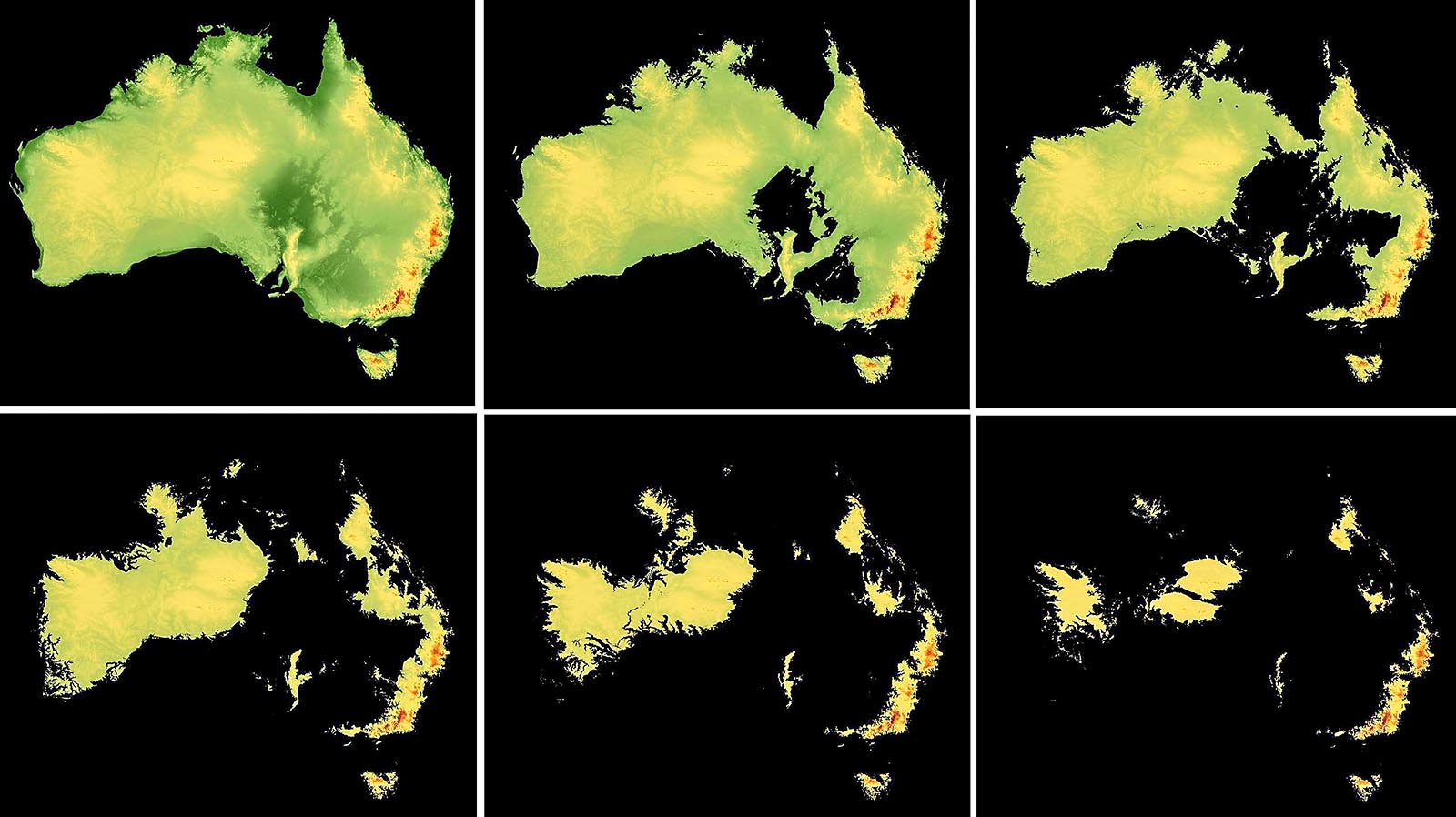

This combination image created from undated handout images by Stephen Young from Salem State College shows the Australian coastline were the sea level to rise by 500 meters.

Photo: Stephen Young/Salem State College via Getty Images

There is often a desire to find a single optimal solution to a climate risk. Usually, the solution proposed is a solid, tangible engineering one—be it a seawall to stop coastal inundation or a desalination plant to tackle water scarcity. Based on my work on several adaptation projects, there is rarely one option capable of managing the risks and consequences that climate change may pose.

Lessons from a Small Asian Nation

A few years ago, I helped develop an adaptation project for the United Nations Development Programme to tackle the risks posed by glacial lake outburst flooding in Nepal. Essentially, climate change is melting glaciers, some of which form large but fragile lakes that may burst and devastate communities, infrastructure, and agriculture in the valleys below them.

The big-ticket item to manage this risk and the one that gets all the attention is to partially drain these lakes through excavation, usually without modern machinery due to the lakes’ locations and access issues. This is difficult, dangerous and labor-intensive work that only reduces the risk for a short time and does not eliminate it completely. This is also a typical hazard-based approach to managing risk that focuses on addressing the source of the risk itself. However, the likelihood of physical hazards occurring cannot always be reduced effectively or efficiently. When this is the case, it is important to understand the consequences of a hazard and how those consequences can be reduced through other nonphysical mitigation options.

A closer look at the final project now being implemented in Nepal highlights the number of adaptation options being used. Apart from structural measures, they include:

- Community-based early warning systems

- Evacuation centers

- First aid and search and rescue training

- Mock drill events

- An information center

- Awareness material including an app and radio broadcasts

Risks from Climate Change for Coastal Australia

Lessons from the Nepal project can also be extended to coastal adaptation in Australia. While the risks and consequences are different, a similar approach to focusing on multiple options that mitigate against both physical hazard and a reduction in consequence is still sound.

A key risk of climate change along Australian coasts is sea-level rise, erosion and storm inundation that can affect the significant population and assets located close to the shoreline.

Figure 1: Coastal Inundation and Coastal Erosion Arise From Intricate Interactions Between Several Drivers

A national assessment of climate change risk to Australia’s coast, undertaken in 2009, indicates that the residential population is exposed to the increasing hazards of climate change:

- Of the 711,000 existing residential buildings close to the water, between 157,000 and 247,600 properties are identified as potentially exposed to inundation with a sea-level rise scenario of 1.1 meters.

- Nearly 39,000 buildings are located within 110 meters of “soft” shorelines and at risk from accelerated erosion due to sea-level rise and changing climate conditions.

- Coastal industries will also face increasing challenges with climate change, particularly the tourism industry, and will need to plan to manage projected risk.

Figure 2: Plan View of the Effect of Coastal Structures on the Shoreline

Although significant and costly damage to property is already occurring in some locations, in most areas this type of risk is real but not yet frequent. In the interim, however, coastal erosion is affecting another key value associated with Australian beaches: tourism and amenity. While seawalls provide excellent protection for highly valuable coastal assets, they do not make for attractive beaches. In fact, they often accelerate the erosion of beaches by reflecting wave energy.

Multiple Adaptation Options

The timing of adaptation options is therefore just as important as the options chosen. In this case, it makes sense to stop building a seawall and to wait on building one for as long as possible, without significantly risking valuable assets. Options to manage the consequences of climate change on tourism and amenity need to be considered. These options can include “beach nourishment” (essentially adding sand to an eroded beach) and increasing vegetation and offshore artificial reefs, which can provide protection and, in some cases, recreational benefits through the creation of surf breaks.

Adaptation strategies in Australia (like Nepal) are also focusing on investments into measures that reduce the consequence on communities, rather than reduce the hazard itself. Where coastal inundation is a significant risk, early warning systems provide residents with time to protect their homes, move valuable items to higher ground and leave before roads are closed. Similarly, information and awareness-raising campaigns help communities understand the risks they face and the actions they can undertake, including purchasing insurance or developing their own personal evacuation plan.

Businesses, too, are an important target of information and awareness campaigns and specific tools. In the short term, business continuity planning is vital to ensuring that businesses are prepared for disruptions and can recover quickly and efficiently. Such disruptions may be physical damage from inundation, or storms or simply a temporary drop in tourist numbers through poor weather or beach condition. In the longer term, businesses and communities may also need to consider the diversification of their economy if it currently relies predominantly on beach tourism. Some areas are already promoting events in their local areas that rely less on beach amenity, such as music festivals and marathons.

In most cases, the approach taken will be to apply a selection of these options concurrently and at a time when they provide the greatest benefit. It is often attractive and straightforward to focus on a single option to manage climate risk. However, a more sophisticated approach that employs a range of options over time will be more effective to mitigate the consequences of the many hazards we face now and will face in the future.