The Chinese Retail Revolution Is Headed West

Founder and executive chairman of Alibaba Group Jack Ma celebrates as the Alibaba stock goes live during the company's initial public offering at the New York Stock Exchange. Shanghai has been developing as a global center of retail innovation.

Photo: Andrew Burton/Getty Images

China’s two biggest online retail groups, Alibaba Group and JD.com, are building retail empires unlike anything yet seen in the U.S. or Europe. After buying stakes or forming alliances with traditional retailers, ranging from convenience stores to big-box hypermarkets over the past few years, these two giants now dominate China’s mobile payments. And they are rapidly bringing to scale new forms of retail, where customers can walk around a store using their smartphones both to pull up information and to pay.

Are the Chinese Writing the New Rules for Shopping?

Though Amazon is widely seen as having set the pace in digital shopping over the past two decades, a second center of retail innovation has simultaneously been developing in Shanghai. The clearest sign that Chinese retailers are also writing the rules for 21st century shopping is in the area of food purchases. Just 3 percent of Americans buy groceries online, compared with nearly 10 percent of Chinese people—and half of those Chinese buy groceries exclusively online.

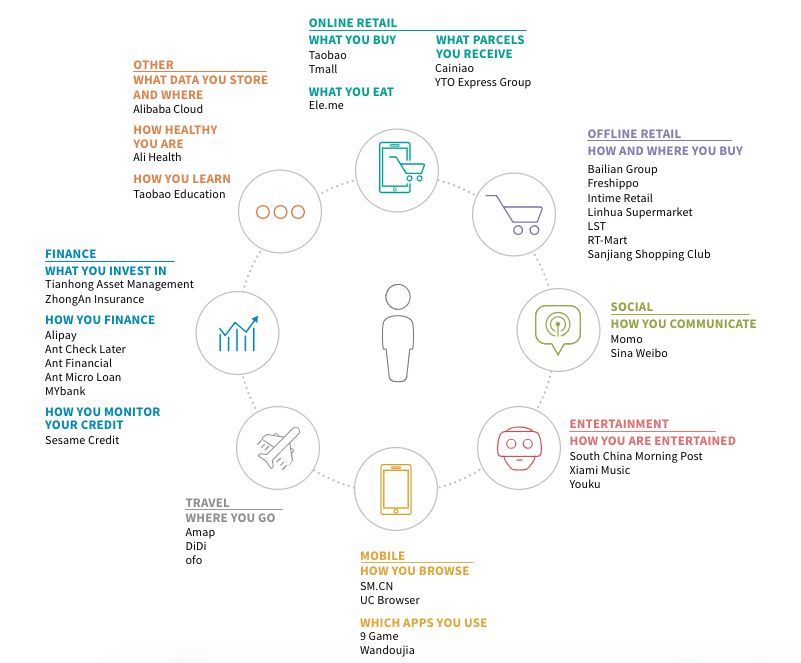

With a share of around one-tenth of China’s grocery retail sales, JD.com and Alibaba are transforming at unprecedented speed into information-fueled networks that gather data from purchases made online or in supermarkets, enabling them to forecast product demand and efficiently coordinate supply and delivery. They also know which websites customers like to visit, the apps they use, and who they follow on social media.

Taking the Fight to the West

The extraordinary growth has its origins in China’s relatively underdeveloped traditional supermarkets, which were falling behind the demands of the country’s burgeoning middle class. China’s explosion in online access—from just 11 percent of the population in 2006 to over half in 2017—made e-commerce a natural alternative. Home delivery is also relatively low-cost, thanks to the density of the cities where wealthier Chinese tend to live.

Now the groups intend to use their new financial and technological might to take the fight to the U.S. and Europe. Alibaba plans to invest $15 billion in global research hubs over the next three years and has been looking at potential sites for European dispatch hubs. JD.com, which has a strategic alliance with its shareholder, Walmart, wants half its profits to come from outside of China in 10 years’ time.

O2O Shopping

Alibaba and JD.com are pioneering new shopping modes known as O2O, or “online-to-offline,” that go beyond the parallel physical and online services offered by most major supermarkets worldwide. While Amazon’s new Amazon Go concept store is a U.S. version of O2O, Chinese retailers are scaling up faster.

At Alibaba’s Hema stores, which numbered 47 by April this year, QR matrix barcodes pull up product information on smartphones—which are also used to select and pay for goods. If shoppers do not want to carry their purchases home, they can request delivery, which is guaranteed within half an hour. But customers can also see and taste fresh food—and a chef will even fry up seafood on the spot.

Exhibit 2: The Ecosystem of Alibaba Covers Every Part of Customers’ Daily Lives

Some of the stores feature futuristic information devices. 7Fresh, launched by rival JD.com, offers automatic payment using facial recognition technology as an alternative to smartphone purchases. It can then convert the data into a chocolate-powder print of the shopper’s face and transpose it onto the frothy milk of a cappuccino. The futuristic experience includes “magic mirrors” that sense when a customer has picked up a vegetable and then display information such as nutritional content and where it was grown. Soon, robot shopping carts will accompany shoppers through a store, avoiding obstacles and relieving shoppers of having to push a cart.

And they are moving beyond food. For China’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival in November, Alibaba set up makeup boutiques that let shoppers try out lipstick virtually and O2O furniture stores that act as showrooms and have QR codes for online ordering.

Paying by Phone

A growing proportion of the transactions in these stores are carried out by mobile phone—and the two empires dominate here, too. Together, they process 92 percent of China’s mobile payments: Alibaba’s system is called Alipay, while rival JD.com is in an alliance with Tencent, which owns WeChat Pay—part of WeChat, China’s largest social app. Mobile phone payments are already used for 35 percent of supermarket purchases in China.

Even when people buy from an independent shop—for a takeout meal, say—the transactions are a valuable source of information on what consumers are buying, where and when. The e-commerce giants can use this knowledge to develop increasingly attractive products and formats. This expertise will then persuade more retailers to sign up with them.

The Financial Firepower

It is notoriously tricky for retailers to expand outside their domestic markets, and the Chinese shopping empires are rooted in their country’s specific retail evolution. But Alibaba and JD.com may have an easier time, since they have already developed significant technology and scale in China—including the means to make online groceries work.

Moreover, Alibaba and JD.com have the financial firepower to buy a company to fill gaps in their operations. Alibaba has a market capitalization of close to $500 billion, while JD.com itself is worth around $60 billion. They have already assembled an impressive number of alliances in China through a wave of acquisitions and partnerships over the past four years; Alibaba has made strategic investments totaling $21 billion in retail alone in just the past two years. The next phase of their big acquisition spree might be outside China.

A longer version of this article first appeared on the World Economic Agenda blog.