The Complex Interdependence of China’s BRI in the Philippines

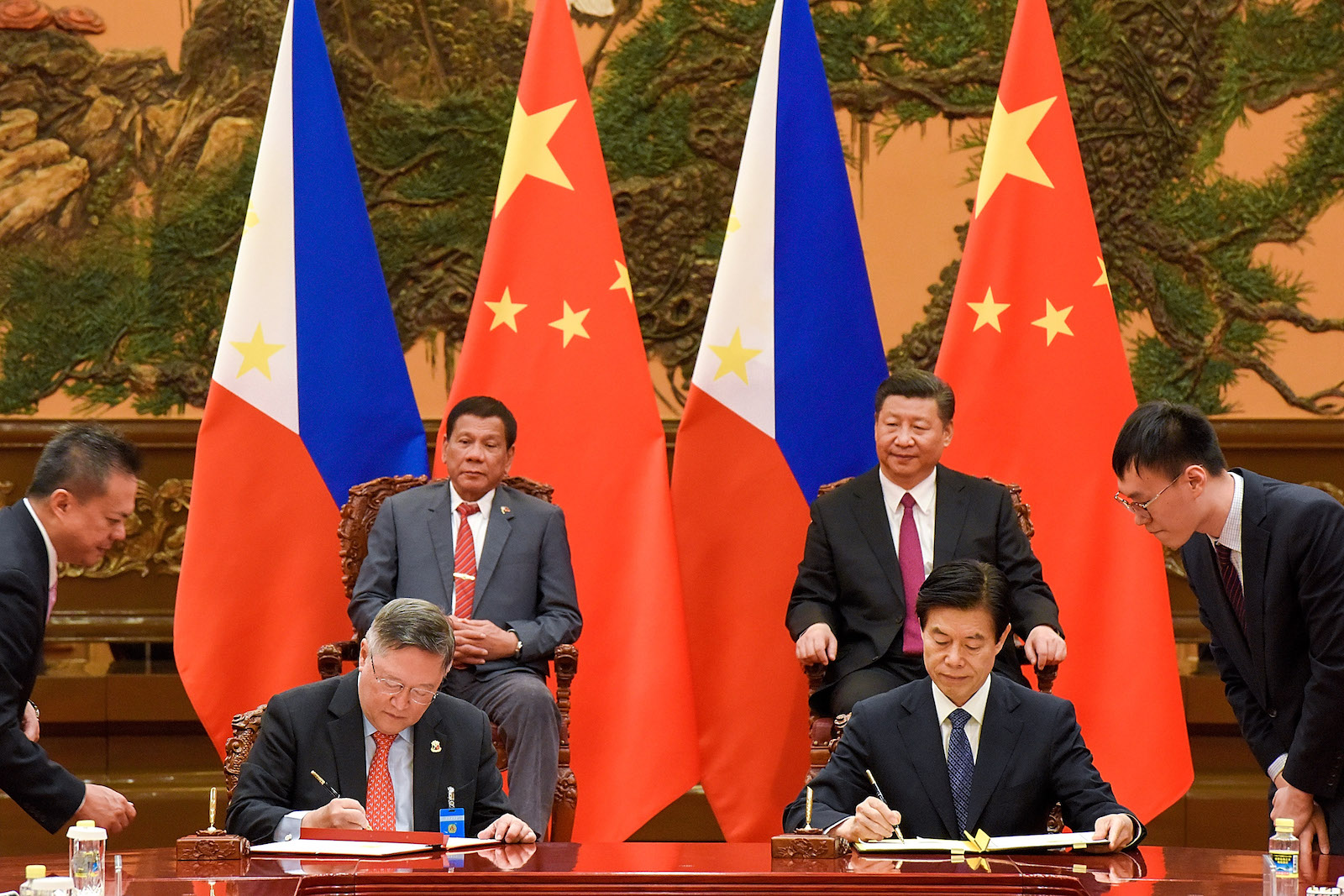

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte attend a signing ceremony after their bilateral meeting during the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation at the Great Hall of the People in 2017 in Beijing, China.

Photo: Etienne Oliveau/Pool/Getty Images

In international relations, “complex interdependence” refers to the multiple channels of interaction and agendas in interstate relations, which involve domestic stakeholders—public and private—on nonmilitary issues. Since the Belt and Road Initiative came into being, most analyses have largely focused on infrastructure development. The BRI not only has the potential to impact a host government’s socioeconomic agenda, but also its overall bilateral relationship with China.

The case of the Philippines demonstrates that to examine the progress of the BRI, it is imperative that it not only be measured through hard infrastructure, but also against the four other major areas of cooperation—policy coordination, trade and investment facilitation, financial coordination and integration, and people‐to‐people ties and connectivity.

Beyond Infrastructure

The 2017 Belt and Road Big Data Report clearly emphasizes on the non-hard infrastructure achievements of the BRI in terms of the following: signed cooperation agreements, established direct air routes, number of trains put into service, investments of Chinese enterprises in BRI countries (and vice‐versa), economic and trade zones setup, signed bilateral currency swap deals, availability of the China Unionpay, sister‐cities forged, increase in tourist exchanges, number of enrolled foreign students in China and implemented visa‐free policies toward China.

Against this backdrop, the BRI should not be interpreted as an initiative that only involves the Chinese government or its state‐owned enterprises, but also private Chinese companies. In the Belt and Road Big Data Report, of the top 50 most involved and influential Chinese enterprises, 42 percent are private, 56 percent are SOEs, and 2 percent are joint ventures. Apart from manufacturing and construction, these companies also operate in the areas of financing and IT, for example, Alibaba, Huawei, Lenovo, Tencent and JD. The report also mentions that the “participation [of private enterprises] into the initiative enhances the reputation and influence of the Chinese brands and products.”

Five Key Areas of Cooperation

Policy coordination: Beijing and Manila signed a Six‐Year Development Program for Trade and Economic Cooperation in March 2017, which aims to gradually harmonize mutual development goals and interests within the BRI framework. This move is also indicative that China will increase its meager investments in the Philippines, which lags behind the U.S. and Japan. Complementing the program is the agreement of the Board of Investments and the Bank of China on the 2017-2019 Investment Priorities Plan for Chinese Companies, which is meant to facilitate business‐matching activities and industrial linkages.

Infrastructure development and connectivity: In this second area of cooperation, China has pledged $7.34 billion in soft loans or official development assistance and grants for large‐scale Philippine infrastructure projects and flagship programs. This amount forms part of $24 billion worth of agreements Beijing committed to President Rodrigo Duterte on his first visit to China in 2016. Interestingly, from 2016, when President Duterte took office, to 2017, loans and grants from China registered an astronomical 5,862 percent increase, according to Bloomberg. The basket of loans through official development assistance programs in two tranches ($7.19 billion) includes dam and irrigation, railways, expressways and bridge projects, among others.

Trade and investment: China became the Philippines’ largest trading partner in early 2017, marking an increase of $15.04 billion (16 percent) from 2016. Furthermore, investments approved by the Philippine Economic Zone Authority and the Board of Investments more than tripled for the first three quarters of 2017 to around $40 million (from $10.9 million in 2016). Remarkably, private Chinese firms are also making headways in penetrating the Philippine consumer market through mobile firms such as Huawei, Xiaomi, Oppo, and Vivo—enterprises that last year ranked among the top 10 selling brands in the world, according to the World Intellectual Property Organization.

The BRI in the Philippines is indicative that the China-led regime is not only a government venture, but is a “whole-of-country” approach.

Even Alibaba Group is making its presence felt in promoting financial inclusion and digital payment services through strategic partnerships with local firms, such as Globe Fintech Innovations Inc. or Mint. Moreover, Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Pay have also signed licensing agreements with Asia United Bank, which favorably enables Chinese tourists to drive the growth of cashless payment systems in the Philippines. In the area of telecommunications, President Duterte even endorsed the participation of a Chinese state-run company to be the third telecom carrier in the country in order to break the long‐standing duopoly and improve the quality of Internet service in the Philippines.

Financial integration and connectivity: The Philippine Central Bank last year officially added the renminbi as part of its international reserves, joining more than half of BRI countries that have already done so. Early this year, the Central Bank additionally approved the Peso-Yuan spot market, which will lower the transaction costs for Philippine and Chinese banks and businesses by reducing reliance on the dollar as the intermediate peg. Around the same time, the issuance of “panda bonds” or renminbi‐denominated bonds worth $200 million began, which could pave the way for more access to Chinese assistance in Philippine financial requirements. Furthermore, the Philippine government has announced plans of partnering with the Alibaba Group to create a more inclusive financial system to help rural communities and SMEs. Their plans would also cut transaction costs for overseas Filipino workers when remitting money to the Philippines through online banking services.

People–to–people exchanges and connectivity: China has become the Philippines’ second-largest tourism market. As of November 2017, 14 new flights connect China and the Philippines, and the Philippine Bureau of Immigration initiated a Visa Upon Arrival scheme for Chinese tourists. Separately, in the area of media and communications, China Central Television and the Presidential Communications Operations Office have signed an MOU for the rebroadcasting of China Global Television Network programs, which are part of the Belt and Road News Alliance of China Central Television.

Win-Win for Both

The significant progress in the BRI’s five key areas of cooperation in the Philippines underscores the rising stakes in and deepening complex interdependence of Sino-Philippine relations.

The BRI in the Philippines is also indicative that the China-led regime is not only a government venture, but is a “whole‐of‐country” approach, which includes the active participation of China’s private sector.

While it is true that the success of China’s BRI would depend on the political environment in each country, China may err on the side of caution by ensuring that proposed projects are transparent, commercially viable, and that participating companies are of good standing. Should Chinese projects flounder, there is a risk of legal action and nationalist backlash, and China, the BRI, and President Duterte would all accrue reputational costs.

Going forward, deepened Sino-Philippine economic cooperation will shift the bilateral dynamics from confrontation to cooperation and create an environment conducive to advancing the overall ties. But sustaining the BRI momentum, apart from risk mitigation strategies, policy guidance or institutionalization—just as what China has done with other countries—may be done through an MOU on Belt and Road cooperation. A joint BRI working committee or BRI action plan may also be formed so that planned projects can outlive brief six-year stints of Philippine presidencies.

This article is based on a paper that the author wrote, which can be accessed here.