The Rising Importance of the ‘Secondary City’

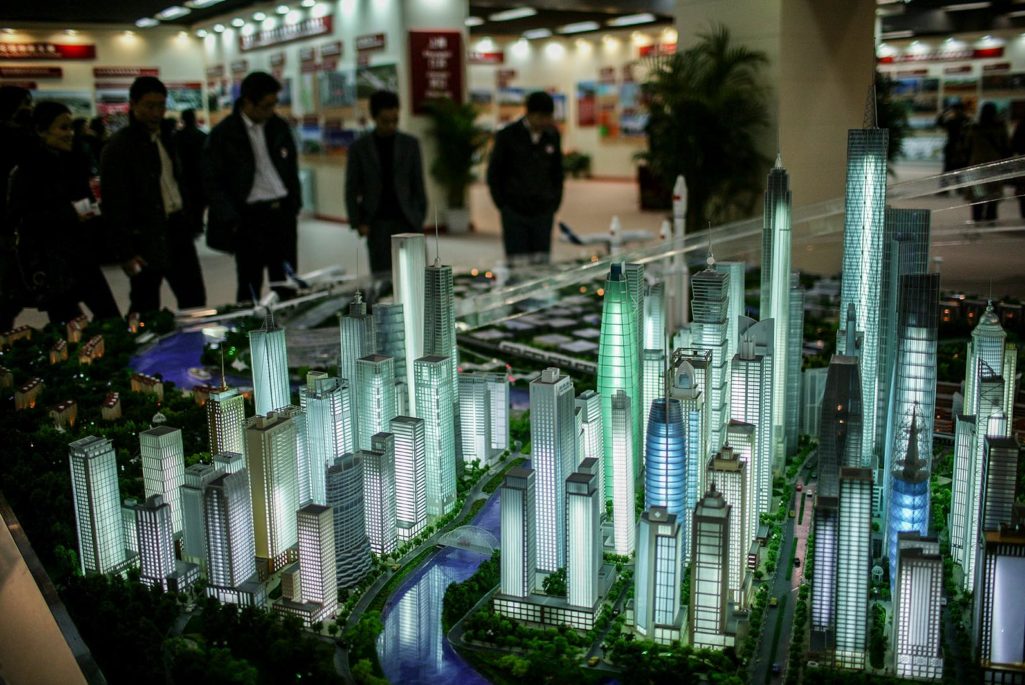

People view models of the Tianjin Development Zone during an exhibition to mark the 30th anniversary of China's reform initiative in Beijing, China.

Photo by China Photos/Getty Images

[Perspectives on Innovation is a regular monthly series featuring content from Perspectives on GE Reports.]

There’s a popular saying in Chinese urban geography and architecture: “If you want to understand 5,000 years of Chinese civilization look at Xi’an, 1,000 years look at Beijing, modern China look at Tianjin.”

This adage might surprise many readers outside of China as Tianjin, like many cities that don’t bear the name Beijing or Shanghai, continues to live in the cognitive shadow of its larger and well-known counterparts. But this port city to Beijing has played a pivotal economic role since the first concessions were granted to European powers following the partial end of the Second Opium War, effectively opening China to foreign trade.

Today, Tianjin is among the country’s five largest urban areas, and it is an industrial powerhouse with a GDP per capita that is outpacing the national average. In 2016 alone, more than 400 Beijing-based companies opened offices in Tianjin and are expected to invest $23 billion in the city. Travel between Tianjin and Beijing is so high that a second high-speed rail link is currently under construction.

Urbanists take note: Secondary cities like Tianjin will have an outsized role in the coming decades. Intermediate cities are among the fastest growing and most creative places in the world, and they’re often the economic engines of their larger counterparts.

There are about 2,400 second-tiered cities worldwide, and nearly two-thirds are in Africa and Asia. Additionally, about half of all urban dwellers live in cities smaller than 500,000 people. Some are gateways to global trade, while others specialize in valuable sectors such as government administration, resource extraction, heavy manufacturing, and technology. Pittsburgh, Bengaluru, and Barcelona are all must-watch secondary cities, as are Abuja, Medellin and Stuttgart.

Despite their more limited fiscal capacity, these cities’ ambition to climb the ranks of world cities has unleashed a wave of experimentation with a host of new urban policies, financing tools, initiatives and partnership strategies.

There needs to be more study of the secondary city. Information and data is often lacking, making strategic planning and research difficult. Much of the talk at October’s UN Habitat III conference in Quito, Ecuador, emphasized the headwinds for secondary cities. This is a shame because such cities, armed with the right insights, could avoid the earlier mistakes of larger metros and often act more quickly to implement projects.

Urbanists take note: Secondary cities like Tianjin will have an outsized role in the coming decades.

One of the highest priority projects underway, as Tianjin has shown, is to build more connectivity as a means to enhance competitiveness and attract talent and investment. The method and degree of connectivity will vary: some cities will need to focus first on digital infrastructure, while others must invest in physical transport links—potentially a leapfrog technology such as the hyperloop.

Defining the Secondary City

University of North Carolina professor Dennis Rondinelli is credited with coining the term “secondary city” in the 1980s in his research on rural economies surrounding these cities. The characteristics of secondary cities vary across national contexts, and there is a lack of consensus on its definition. Typically, the population size falls between 10 to 50 percent of the country’s largest city, and the residents often assume administrative, economic, or logistical roles outside of the country’s leading metropolitan area.

Cities Alliance, a joint World Bank and UN-Habitat initiative, has produced a body of literature on secondary cities and divides them into three spatial categories:

Subnational cities: Centers of local government, industry, agriculture, tourism, and mining. These cities are the most common and hold important economic and functional roles. Think Vancouver, Philadelphia, Basel, and Milan.

City clusters: Satellite and new town-cities that surround larger metropolitan regions. These settlements usually develop alongside decentralization and firm relocation to areas less than 50 km from historic city centers. The satellite town Navi Mumbai is an example of this type.

Corridors: Urban growth centers planned or developing along major transport corridors. These cities are among the fastest growing and are associated with improvements in transport infrastructure. New cities rising along the Silk Road between Asia and Europe fall under this category.

City Linking as a Strategy for Growth

Decision-makers all over the world are realizing the importance of connecting dominant cities with their secondary counterparts to create highly productive and competitive urban clusters.

“The functional federation of cities across political borders, united by infrastructure and technology systems, is likely to become a major feature of global cities by the mid-twenty-first century,” says Greg Clark of the Brookings Institution.

In New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s Upstate Revitalization Initiative aims to support intra-regional connectivity through expanded Bus Rapid Transit lines. China implemented an aerotropolis-based development strategy in Zhengzhou, the likely birthplace of your iPhone, in just one piece of its colossal New Silk Road project. An EU report on secondary cities found that connectivity is highly correlated with per capita GDP.

The argument for city-to-city linking comes down to increasing opportunities for economic exchange. Connectivity allows secondary cities to integrate into regional labor and investment pools and access new supply chains and consumer markets.

City-to-city links could also lead to rebalancing growth and mitigate the capacity burdens on larger cities in housing and transport infrastructure. Lastly, linked municipalities could result in more coordinated economic and infrastructure strategies for regional development. With the advent of the hyperloop, the potential impacts are even greater, allowing for wider spatial opportunities for employment and living, and the creation of “mega-regions.”

Several of the Hyperloop One Global Challenge semifinalists have offered routes that connect key secondary cities to primary cities. In South Korea, a team has proposed to link Busan, an important port city, to the capital, Seoul, which contains almost a fifth of the entire country’s population. In the United States, a regional planning commission wants to link Chicago to Columbus and Pittsburgh, creating a Midwest megaregion. An architecture firm proposes to connect Guadalajara to Mexico City, and a student-led team in the United Kingdom wants to link Edinburgh to London.

These proposals demonstrate that we should take seriously the considerations and future development of second-tiered metro areas and promote policies and ideas that target inter-city connections.

This piece first appeared in Hyperloop One’s blog.