World Oil Trade Hinges on These 8 Vulnerable Chokepoints

A 54,000-tonne tanker flying a Liberian flag is seen stuck at the Suez canal on March 28, 2010. Traffic in Egypt's Suez Canal was disrupted after the oil tanker ran aground in the strategic waterway.

Photo: STR/AFP/Getty Images

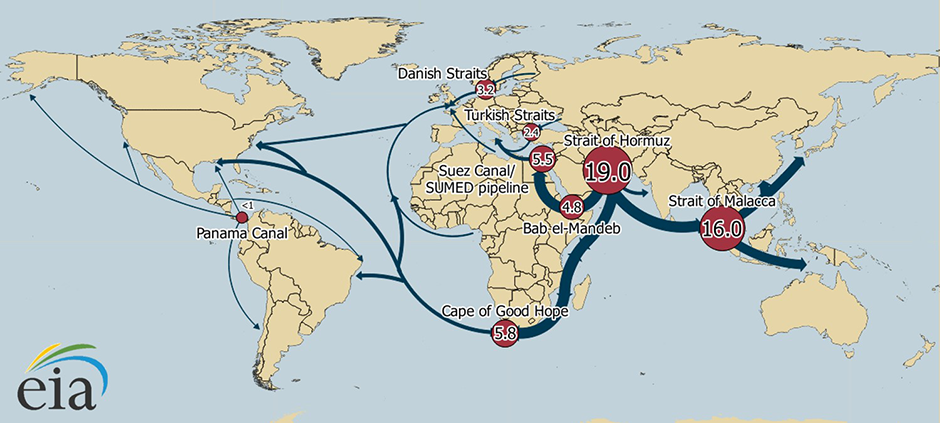

About 61 percent of the world’s oil supply moves through a handful of vulnerable maritime chokepoints, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Some of these eight chokepoints are so narrow that restrictions are placed on the size of the vessel allowed to navigate through them. Most chokepoints can be circumvented by using other routes, but in some cases no practical alternatives are available, the EIA said. Rerouting to avoid chokepoints can result in substantial disruption, often requiring ships to detour by thousands of miles and adding significantly to transit time.

The world’s energy markets rise and fall on reliable transport routes. “Blocking a chokepoint, even temporarily, can lead to substantial increases in total energy costs and world energy prices,” the EIA said. “Chokepoints also leave oil tankers vulnerable to theft from pirates, terrorist attacks, political unrest in the form of wars or hostilities, and shipping accidents that can lead to disastrous oil spills.”

Here’s a brief look at the eight chokepoints:

The Strait of Hormuz

This is the world’s most important chokepoint. In 2015 about 30 percent—17 million barrels a day (b/d)—of all seaborne-traded crude oil and other petroleum liquids flow through this strait. In 2016 that figure jumped to a record high of 18.5 million b/d.

About 80 percent of the crude oil moved through this chokepoint went to Asia markets, the EIA estimates. The strait can handle the largest oil tankers in the world, but it could be subject to geopolitical uncertainty at any time. Iran has previously made noise about disrupting traffic in the strait; at one point Tehran threatened to mine the waterway. And in 2015 it blew up a full-size model of a U.S. aircraft carrier in the strait.

There are bypass options, but most aren’t operational. Only Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have pipelines that can ship crude outside of the Persian Gulf and have the additional capacity needed to bypass the strait, the EIA said.

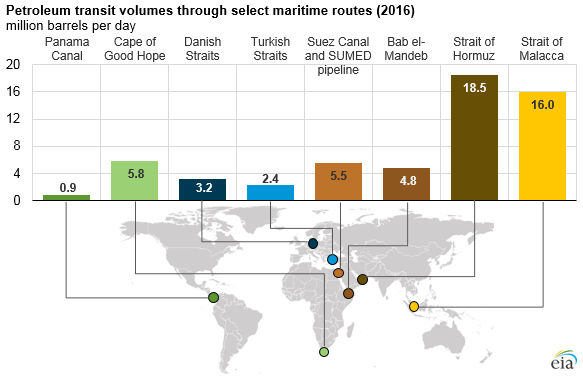

All estimates in million barrels per day. Includes crude oil and petroleum liquids. Based on 2016 data. Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Strait of Malacca

This is the shortest passageway, connecting the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean. This route supplies oil to China and Indonesia, two of the fastest growing economies in the world, and is the primary chokepoint in Asia. Some 16 million b/d flowed through here in 2016, making it the second most important energy passageway.

The Strait of Malacca is among the most narrow chokepoints in the world, measuring only 1.7 miles at its widest point. “If the Strait of Malacca were blocked, nearly half of the world’s fleet would be required to reroute around the Indonesian archipelago,” the EIA said. “Rerouting would tie up global shipping capacity, add to shipping costs, and potentially affect energy prices.”

Complicating matters, the region is now a hotspot for piracy and maritime kidnappings.

The Suez Canal

This passageway accounted for about 9 percent of the world’s maritime oil trade in 2015 or 5.5 million b/d.

The canal was expanded in 2010 to allow 60 percent of all tankers in the world to pass through, the EIA said. Although the region is subject to political unrest, the fall of Hosni Mubarak in 2011 hardly deterred shipping. Still, security remains an issue. A planned rocket attack on cargo ships passing through region was thwarted in 2013.

Bab el-Mandeb Strait

If the Bab el-Mandeb Strait were closed, it could keep tankers in the Persian Gulf from reaching the Suez Canal, diverting them around the Cape of Good Hope, another of the world’s chokepoints. An estimated 4.8 million b/d flow through this strait en route to Europe, the United States and Asia, the EIA said.

The strait is another restricted passageway, only 18 miles wide at its narrowest point, which limits tanker traffic to two, 2-mile-wide channels, the EIA said.

Turkish Straits

The Turkish Straits are important for shipping oil from the Caspian Sea region; however, the straits have seen declining volumes since 2011, falling to 2.4 million b/d in 2016. Oil moving through these straits supplies Western and Southern Europe.

The straits are only a half mile wide at the narrowest point, making them among the most difficult waterways to navigate larger vessels.

The Panama Canal

Ironically, the canal isn’t a significant route for U.S. oil, and its recent expansion is unlikely to significantly change crude oil and petroleum product flows, the EIA said. Only about .9 million b/d flow through the canal.

The narrowest point of the canal is only 110 feet wide, which means larger super-tankers have to avoid it entirely.

The Danish Straits

This passageway is a crucial one for Russian-based oil exports to Europe, connecting the Baltic Sea to the North Sea. An estimated 3.2 million b/d of crude flowed through here in 2016.

Cape of Good Hope

The cape isn’t technically a chokepoint, but its status as a major global trade route qualifies it as chokepoint as it’s responsible for about 9 percent, or 5.8 million b/d, of all the maritime oil trade.

The cape is also a standard alternate route for ships traveling westward wanting to bypass the Bab el-Mandeb Straits or the Suez Canal. However, diverting around the cape increases cost and shipping time—as much as 15 added days in transit to Europe and 10 days to the U.S.