3-D Printing Won’t Kill Global Trade … Yet

Companies like Adidas and Nike hope that additive manufacturing can turbocharge their supply chains. The goal is to be short and fast.

Photo: John Biers/AFP/Getty Images

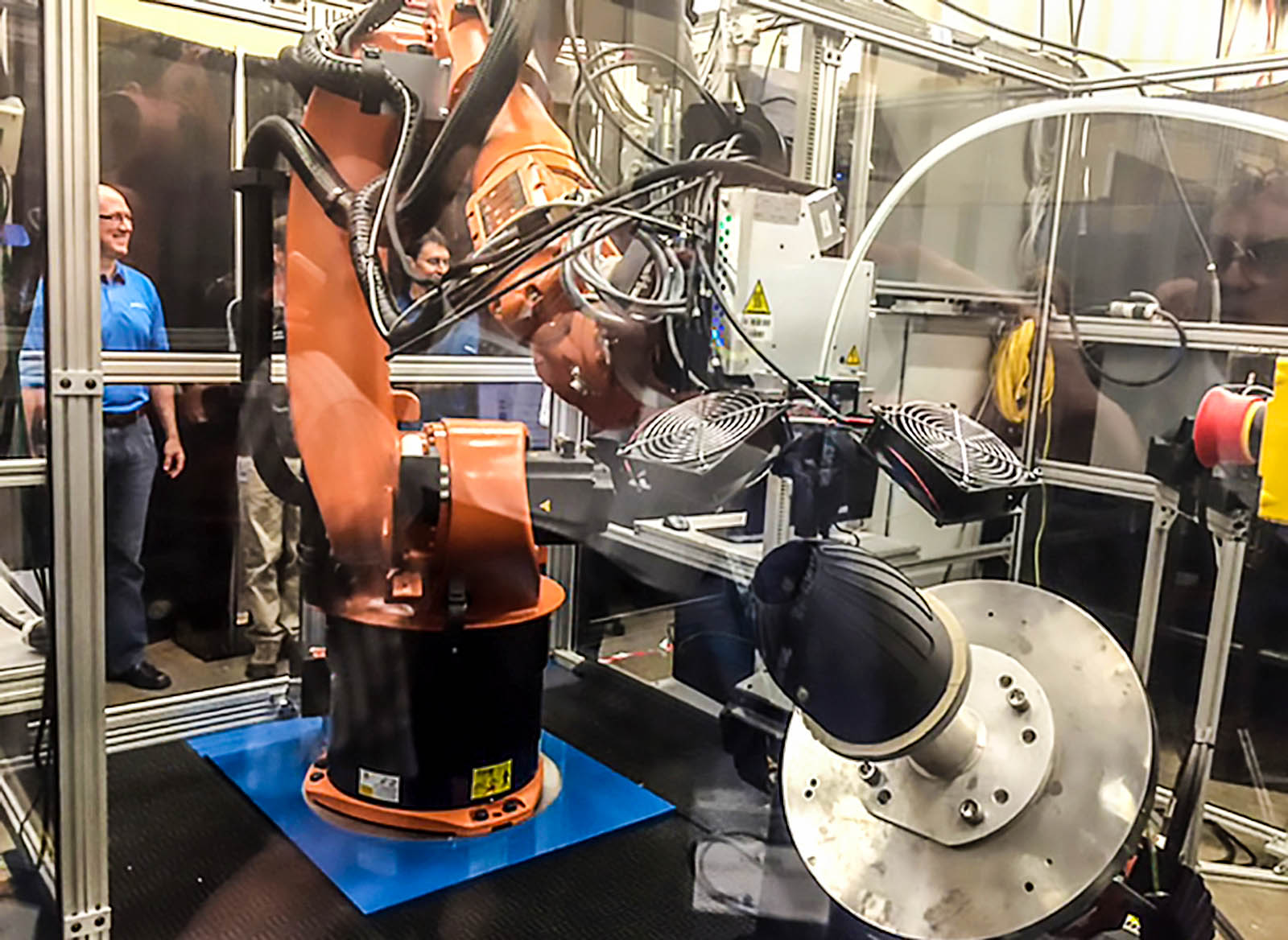

Last year Adidas opened its first 3-D printing plant for sports shoes—its highly automated, so-called “speedfactory”—in Ansbach, a small town in Bavaria in the southeastern part of Germany.

The German sports-goods company announced similar plans for Atlanta in the U.S., as well as for other Western European markets. In the mid-run, these factories will each manufacture half a million pairs of shoes per year.

Traditional production can require a one-year process for design, sampling and large-scale manufacturing. 3-D printing-based production—also known as additive manufacturing—helps to bring factories closer to customers and products to the markets faster.

The new way requires, at its best, only days—reducing lead times on average by 66 percent. The shorter the cycle, the more retailers can place orders based on actual sales instead of estimates. Suppliers deliver what is really needed. Finally, consumers get what they want.

Eventually, consumers will be able to have goods produced by a printer near to them, ready for pick up, or have goods delivered or printed at home if a printer is available there.

Distributed manufacturing is the name of this concept, and it reduces inventories and carbon footprints. In addition, 3-D printing makes very different and new product designs possible.

Unsurprisingly, companies like Adidas and Nike want to turbocharge their supply chains. The goal is to be short and fast.

But it’s not all about speed. Adidas says that, in parallel to its speedfactory-based, short-and-fast supply chain, it will also expand its traditional, longer-and-slower supply chain. Here are four points illustrating the limitations of 3-D printing:

1. The economics for 3-D printing-based mass manufacturing don’t yet work out.

Many experts doubt that they will in the foreseeable future, either. The unit costs for thousands of mass-produced, identical parts, such as industrial components, are still simply much lower than those manufactured by any other means.

3-D printing also falls short where natural fabrics such as leather, cotton, wood and stone, or marble, granite, and minerals, such as rare earths, are needed—either to ensure the functionality of a product, or simply because they are demanded by the customer.

Therefore, it might well be a myth that 3-D printing will replace mass manufacturing by mass customization, even in the midterm.

Adidas plans to grow its global athletic wear sales from $290 billion in 2017 to $355 billion in 2021. These additional sales will hardly be reached through the application of just one technology. Reaching the target will require a mix of technologies and supply chains. Furthermore, moving the manufacture of all 301 million pairs of shoes Adidas produces each year to new sites—not even counting its double-digit annual growth—would imply tremendous effort, cost and risk. The investment would be very high—just imagine the number of new speedfactories needed.

2. The technology works best for personalized goods.

3-D printing generates significant value in the field of highly personalized goods and meeting demand for smaller quantities at affordable prices. Parts can be printed on demand, obviating the need for storage.

Boeing deploys 3-D printed parts in jet engines. The technology has the potential to save the manufacturer $3 million in construction costs on each B787 jet it builds. Deutsche Bahn has started to print spare parts to accelerate maintenance processes. And Daimler uses 3-D printing to personalize parts and vehicles and manufacture smaller batches for automotive customers.

In health care, 3-D printing applications range from brain and organ models to personalized plaster casts and low-cost prosthetic parts. But an example for a global scale supply chain is lacking.

The opening of the speedfactory can be considered a Kitty Hawk moment in the history of additive manufacturing. It is an example of highly automated production in high labor cost countries.

But the most popular technologies currently used in 3-D printing were developed in the early eighties. We still might need to wait some time before we see the first mass-manufactured, 3-D-printed jet plane taking off.

3. Personalization changes the game—but not entirely.

Mark Zuckerberg still buys only one piece of cloth—a grey T-shirt he wears every day—and so do millions of consumers.

One-color sports shirts do not need to be manufactured at the place of consumption, as high-speed delivery is not a prerequisite for success. And this is valid for most long-lasting consumer goods, which represent the major part of today’s consumer demand.

Only designer goods and fashion require a high level of convenience, flexibility, speed and regularly changing models. However, smart design enables personalization by using mass-produced parts to produce a broad variety of different models. Different luxury bags of the same brand can be made of the same parts—just stitched together in different ways.

We’ll need to wait some time before we see the first mass-manufactured, 3-D-printed jet plane take off.

Postponement is another way to enable personalization in mass production: by dividing the manufacturing process into the two phases of manufacturing base products and then customizing base products. The base products are mass-manufactured, while finalization happens in or close to the market.

Postponement pushes the finalization of a product down to the end of the chain—for example, the color and certain parts come last. This is a process commonly used in the automotive industry.

3-D printing will complement this practice by enabling unique parts to be added at the end, while the base product will continue to be mass-manufactured in traditional ways.

4. Manufacturing technology and customer wants are not the only factors at play.

Supply chains are shaped by many factors.

First, different supply chains—fast and slow, short and long—respond to different needs: from bringing resources to the factories near consumer markets, to moving parts through global value chains, to connecting the different players within industrial clusters.

Second, many external factors shape supply and value networks. Among these are geopolitical risks, the availability of skilled workers, the quality of infrastructure, tax considerations, the cost of land and energy, and the time and effort to obtain licenses.

Different locations have different capabilities, possibilities and brandings: “Made in Germany,” for example, is a unique feature, which can hardly be globalized. These factors not only determine the design of global supply chains, but also the speed and magnitude at which technology-driven nearshoring can advance.

Third, the capacity to manage change and complexity is limited. Changes can have huge implications—the workforce needs to be taken into account and assets might not have been written off or amortized yet. Management needs time and energy to keep its focus on customers and markets and to ensure the stability and smooth continuation of the business.

Fragmentation has its limits. How many sites can a management team successfully manage in light of an increasingly complex and competitive business and operating environment?

Focus has major benefits; therefore, management will always seek a certain level of aggregation and concentration of activities and efforts at certain locations to ease the management burden.

Companies will continue to test new technologies and apply them where it makes sense. 3-D printing is one useful enabler to respond to customer needs and wants; an important tool for designers, operations and supply chain managers. The technology will surely further improve and so will other manufacturing technologies.

Long supply chains will still have their role to play. And so will international trade, which helps to keep diverse global production networks going.

In summary, 3-D printing holds high potential in those areas where it is a good fit. But, for now, its revolution has clearly not yet come.

This piece first appeared on the Agenda blog of the World Economic Forum.