Are Robots the Answer to China’s Burgeoning Health Care Needs?

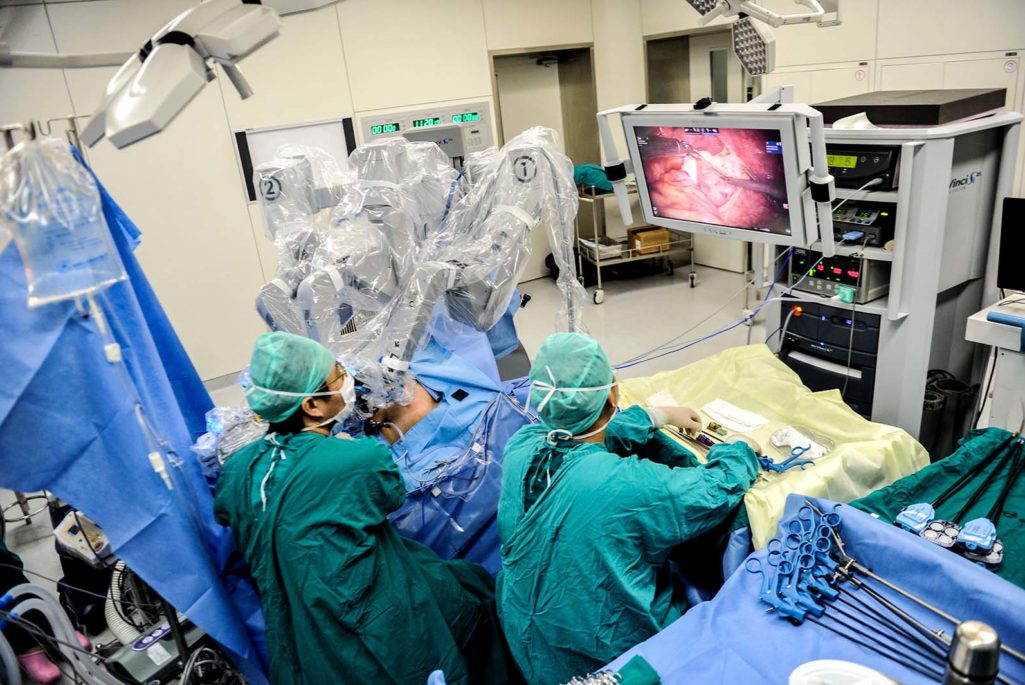

Surgeons operate a da Vinci Surgical robot to remove a tumor at the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University on April 15, 2015 in Guangzhou, Guangdong province of China.

Photo: VCG/VCG via Getty Images

A few years ago, the Western media was quite puzzled by China building many new towns—apparently far from anywhere. Now the same media is concerned to learn that China wishes to build 400 new hospitals.

But let me offer an explanation of sorts. China, the U.S. and Europe have almost the same surface area, while China has a population of 1.4 billion, Europe 750 million and the U.S. only 320 million.

China’s government has to look after its people like all other governments. However, China is a special case as its rural-to-urban migration is now in full swing, years after the rural depopulation of Europe and the U.S. Hence the need for new townships and accompanying services.

A Plan for the Future

In March 2015, China’s National Council unveiled its five-year plan for a national health care system that noted, despite a recent rapid growth in such care, it needed more health support of all types. By the end of 2013, China had 974,400 medical institutions and 24,700 hospitals with 6.2 million beds. There were 7.3 billion clinic visits, growing at 7 percent annually, and 191 million hospitalizations, growing at over 12 percent annually.

The 2015-2020 plans called for a great increase in provisions, partly because of the need to service approximately 240 million elderly people (above the age of 60) by 2020. This number equates to 17 percent of the population projection in 2020. They responded by calling for a further five million beds.

Consider all the institutions needed in China’s new towns. In addition to hospitals and their staff, there is an accompanying need for schools, transportation stations, airports and suppliers of services like telecommunications, broadcasting, electricity, water and so on. All of these services need skilled people in order to operate correctly. The skills needed for these services demand time; China could also benefit from more young people entering the workforce at earlier ages.

A doctor, perhaps the most extreme case, takes 18 years from birth to university entrance, another four or five years before graduation, and one or two more years under an apprenticeship scheme before being allowed to treat patients unsupervised. About 25 years pass before a newborn might become a doctor. And during that time span we have to assume that the government, regional and city planners were developing sufficient teaching capacity.

Is this reasonable? Thirty years ago, did China’s National People’s Congress declare it was increasing doctor training capacity in planned phases? Very doubtful, as that would be forecasting beyond any imaginable future, not only by the Chinese government, which does think long term, but by any other government.

Enter the Robot

Winding back the clock, the decreasing price and increasing power of computers opened up the study of “Expert Systems” in the 1970s that blossomed in the 1980s. However, academics soon found that unlike the human brain, a computer brain could not make intuitive leaps, and the expert systems had to be confined to quite small domains of knowledge, although their ability to analyze tirelessly and accurately was soon lauded.

The Chinese government can advance health care and provide a useful model for others by tapping into robotics.

Academics also found that it took a long time to elicit knowledge from a human expert and then code the knowledge into the computer. Now, with much larger and faster computer systems and different computing modes, they learn faster. A Google Research blog concludes that computers seem to be self-developing linguistic semantics. However, not all of this is magic. There is still much human input needed, but the upshot is that while it may take a long time to train one robot, we can replicate and deploy it rapidly, whereas human education cannot be hurried.

China is the largest purchaser of industrial robots globally—think of the assembly lines of cars, phones or footwear. Increasingly, these quite simple machines have been pressed into services demanding fine precision, such as operating inside the human body while being controlled remotely by a surgeon.

Of course, local staff is needed to care for the patient, but the rare skills of the surgeon can be presented digitally from anywhere, reducing overall specialist training needs.

Researchers are also finding that robots can be used in elderly care homes, not only to deliver medication to patients in a timely manner, but also to be the equivalent of a pet providing love to a lonely patient. The result is that palliative care is increased without a great need to employ more nurses.

Education in remote rural areas is also enhanced with the help of computers, so that self-learning can take place without the need for teachers working face to face.

Robots, therefore, offer great potential. They reduce the number of workers needed to do dirty, dangerous tasks and conduct repetitive, boring assembly. And they can augment human skills when either strength or delicacy is needed.

Coupled with the computer’s ability to analyze vast data quickly, robots can ostensibly make complex decisions, allowing us an easier lifestyle.

Deploying the Robot

Given China’s almost unique global situation—a very large and aging population with a large national sovereign fund—it is possible for the government to advance health care rapidly and provide a globally useful model for others to follow by tapping into the vast resources at its disposal.

Leading in any sector is costly and time consuming, but China has the will to do this in health care. We already see in Hainan island large specialized villages with nearby hospitals being built to care for older people, who wish to retire away from the winter chills of the northern parts of the country.

But the overarching solution is the deployment of robots across all sectors. At present there is some resistance as staff do not wish to lose their jobs, but the same people will wish later to live a fulfilling life in retirement and will hope the robots work well.

To achieve this future, research and practice need to begin as soon as possible within China’s long-term plans. By embarking on this journey now, China may well show the rest of the world a new era in health care.

A version of this piece first appeared in The Straits Times.