Automation Isn’t the End of the World. Here’s Why

The humanoid diving robot “OceanOne” is shown during a presentation in Marseille. The robot was tested during an archeological dive at 90 meters deep.

Photo: Narinder Nanu/AFP/Getty Images

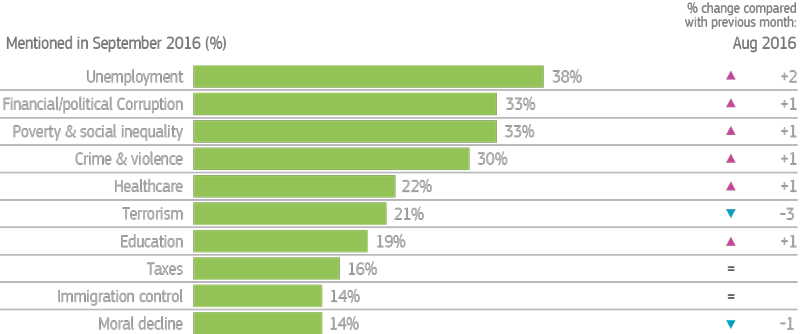

What keeps you up at night? For many people worldwide, the answer is unemployment. Work is not just what allows us to sustain ourselves and our families; it expands our possibilities to be and do what we aspire to, and it gives meaning and rhythm to our endeavors as part of a broader social contract. This is why, in times of “polycrisis” and broader economic transformations, we dread losing what we hold so dear to a presumed automation apocalypse.

Representative sample of adults aged 16-64. September 2016: 18,014; August 2016: 18,042. Source: Global Advisor

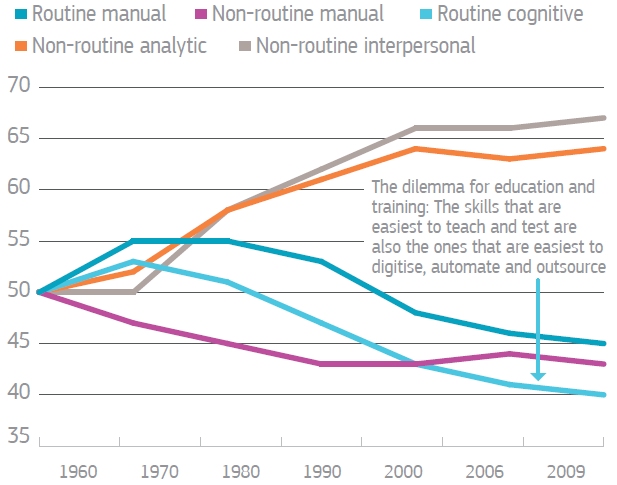

It is true: If a routine task can be performed cheaper, faster and better by a robot, there is a chance it will be. What is also true—and even more certain—is that machines push us to specialize in our competitive advantages: More “human” work, creative and social intelligence, interpersonal and non-routine tasks are what make us resilient and adaptive to change.

The future of work is about much more than automation. It is about equitable access to opportunities and accessibility. It is as much about finding employment as being entrepreneurial.

The future of work is about new ways to better preserve, share, spread and generate economic and social value. Advances in knowledge and technology have already empowered us with novel skills and solutions. They come down to three “Cs”: circular, collaborative and connective.

A Look into the Future of Work

In the 21st century, progress is about circling the economic and social square. As we reach planetary boundaries and unemployment tops our hierarchy of concerns, we can no longer afford to waste our capital, whether natural or human. A circular economy can help put an end to that.

Investing to make buildings more sustainable, for example, means more energy-efficient houses that curb pollution and help families save more on their energy bills. At the same time, making apartments smarter brings construction workers—who were hard hit by the 2008 financial crisis—back into the labor market and equips them with new technical skills.

In the same way, projects such as The Last Mile turn inmates—who are generally considered economically passive members of society—into digital entrepreneurs, making them economically active while they are incarcerated and preparing them for reintegration when they are out.

Preserving and uncovering value is not enough; it must be shared and accessible. This is ever more possible in an increasingly collaborative economy. Communities in Brooklyn, New York, are creating a shared economy for peer-to-peer energy exchange to be more resilient and take neighbors out of energy poverty. So if a house’s solar panels produce excess electricity that would generally go to waste, that surplus can be transferred to another, immediately and at a locally determined price. Similarly, as cars are, on average, parked 92 percent of the time, why not share them with those who face obstacles to mobility and maximize everyone’s benefits?

Finally, circular and collaborative innovations would not run as efficiently—if at all—had we not entered the connective economy. Thanks to connectivity, drones can be activated with one click to deliver medicines to rural areas, saving lives that an ambulance would have never reached. The most expensive part of that drone—which can be built in 15 minutes—was probably the result of a worldwide hackathon that made it openly accessible and brought its cost down to $8. Connectivity has extended our imagination, allowing us to engineer solutions to seemingly unsolvable problems and invent new professions that, not long ago, only belonged to science fiction.

Connectivity also means that we can invite more talent—all talent—into the future workplace. Initiatives such as Stevens use virtual exchanges to build cross-cultural skills and facilitate the integration of today’s immigrant children into tomorrow’s ever more diverse workforce. The elderly and people with disabilities can overcome physical limits and enter digital workplaces. Women can tear down the last barriers of gender discrimination.

When we look at the future of work with circular, collaborative and connective lenses, it stops looking like the automation apocalypse. These “three Cs” are not just attributes of an economy that may well yield minimum waste and maximum benefits for a larger number of people; they are qualities of a networked society in which we become individually stronger when we act collectively. They are critical skills that allow us to turn specific problems into systemic possibilities and shape the future of work we want. They demonstrate that, in the 21st century, solidarity is not just an ethical quality, but it makes social and economic sense. A robot cannot see and seize that.

This piece first appeared on the World Economic Forum’s Agenda blog.