Are Electric Vehicles Really Green?

A worker assembles the interior of an electric car on the assembly line at a production facility on June 08, 2021, in Germany. The process of manufacturing a vehicle, excluding the battery, generates around six tons of carbon emissions on average.

Photo: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

When it comes to transport’s carbon footprint, increasing attention is being paid to the carbon impact not only of the fuel type but of the parts used in the assembly of a vehicle, whether electric or petrol-powered.

A new report on the materials used in the vehicle manufacture by the Brussels-based Transport & Environment think tank (T&E) shows that EVs should have far fewer carbon emissions in their manufacturing process, though much depends on how the battery is made.

Lucien Mathieu is road vehicles and mobility analysis manager at T&E. BRINK spoke to him about how the process of manufacturing a vehicle determines that vehicle’s carbon footprint.

MATHIEU: The process of manufacturing a vehicle, excluding the battery, generates around six tons of carbon emissions, on average. Of course, it depends on the size of the vehicle, but that includes acquiring the primary materials and all the manufacturing processes.

The main difference in the carbon footprint of the materials used in an electric car versus a petrol car comes down to the battery. An electric engine is much smaller and much lighter than a petrol or a diesel engine, which is much more complex and, therefore, requires significantly more materials and manufacturing.

Sourcing the Energy

Even more important in terms of reducing the carbon impact of the production of a vehicle — whether electric or not — is the source of the energy used by the car producer on its site. It matters whether the car producers use renewable electricity and whether their manufacturing processes are energy efficient. This is essential when seeking to reduce manufacturing emissions and is especially true in the production of the EV battery.

We have a tool online that allows you to look at the entire lifecycle of a vehicle and compare the carbon emissions of any car, petrol or electric, to see where the battery is made, what type of electricity is used to recharge the electric car, etc.

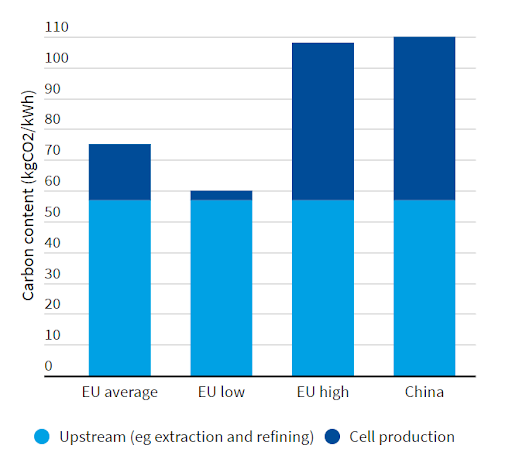

For an EV, the second most critical element after the source of electricity is how the battery is actually made. Manufacturing an average battery will add between four to five tons of carbon dioxide emissions. We divide these impacts into two phases. The first phase, the upstream parts, is the extraction of the raw material for the battery and the refining of those materials.

The second stage is manufacturing in huge battery factories that are setting up shop around the globe. If you produce a battery with electricity generated by coal, then the battery cell production stage will have a relatively high impact, whereas, on the other hand, if you use renewal electricity, the impact of battery production is only between a third and a quarter of the impact of the upstream matter extraction. This offers a huge potential to reduce emissions from battery cell production.

Recycling Will Be Critical

BRINK: Right. How much is the carbon footprint dependent on recycling materials?

MATHIEU: We don’t have a lot of data on battery recycling because only a very small number of EV batteries have already reached their end of life. Batteries will stay on the road for 10, 15 years, so we have very few batteries that are coming to the recycling stage.

And the few that are coming to the recycling station are closely kept by the battery producers because, for them, it’s a very valuable opportunity to learn and develop their in-house recycling processes.

BRINK: How much impact will the EU’s new battery law have?

MATHIEU: The law is now being discussed at the EU level between the parliament and in the member states. And it’s a major breakthrough in terms of how we address batteries. This will oblige all batteries placed in the market to be collected and recycled. And it will have specific material recovery targets, such as 95%, when it comes to cobalt, nickel, manganese or copper. Ninety-five percent of those materials will have to be recycled and recovered to be used in new applications, like for a new EV battery.

There is still a bit of a gap in terms of the knowledge that we have, but we expect recycling to play a significant part in reducing the emissions from the battery footprint, in particular for reducing the amount of primary raw materials that we have to extract from the ground.

Responsible Mining

However, we’re still going to need so much more raw material in the future to meet expanding demand for decarbonizing the road transport sector, so extraction will still have to increase as well. There is a whole section in this new EU law about responsible mining, which obliges the battery-makers to do a full due diligence and risk assessment and mitigation of their supply chain in the identification of the risks linked to extracting the materials.

This can be an environmental impact, for example, on the water toxicity, but also the ethical and social impacts, for example, child labor in Congo. These are things that will be addressed as well in this new battery law.

The last pillar of the law is on the type of carbon footprint calculation.

The European Commission will be developing a methodology to calculate the precise carbon footprint of the batteries, taking into account all the different variations that you can have, for example, if the nickel is from Indonesia or it’s from South America, if the battery is produced with clean electricity or not. So all these questions will be taken into account.

The European Commission will then put in place strict requirements on the maximum carbon footprint of batteries placed in the market in Europe.