Human Mobility and Climate (In)Action

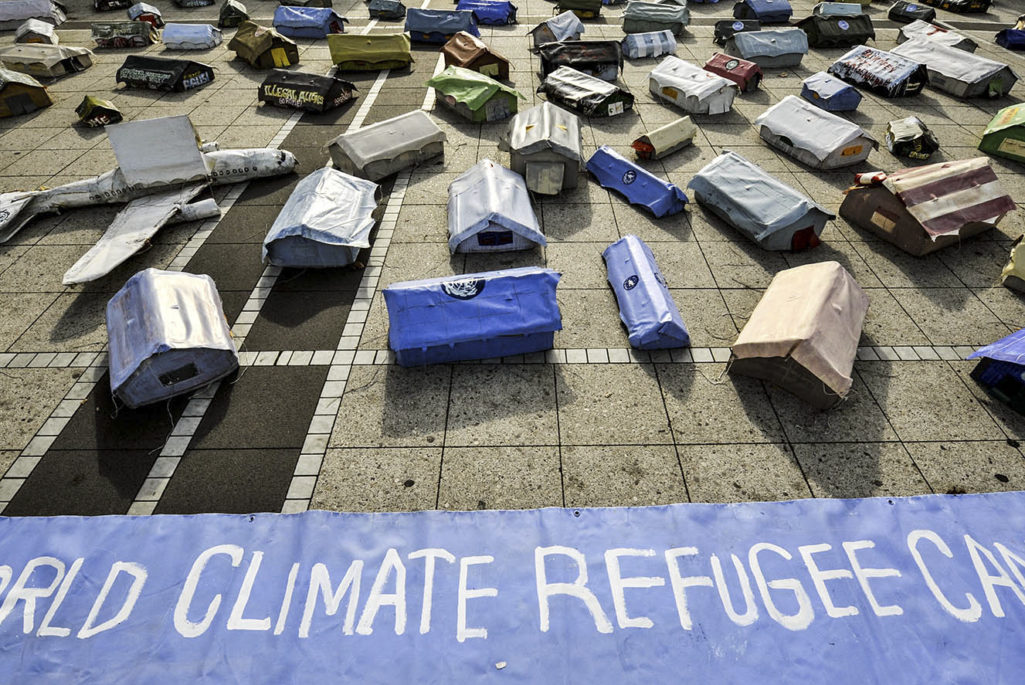

View of miniature tents placed outside the headquarters of the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. German artist Hermann Josef Hack created a "Climate Refugee Camp" made up of three hundred miniature tents to call attention on the plight of thousands of climate refugees whose livelihoods are threatened by climate changes.

Photo: John MacDougall/AFP/Getty Images

Questions related to human mobility are very much in the spotlight due to the current European migration and refugee crisis and the numerous tragedies we witness each day. In parallel, the COP21 climate conference in December pushed the issue of climate change high on the political agenda of many countries, with 2015 being recorded as the hottest year on record.

The intersection of these two contemporary issues raises many complex questions around the nature of climate-related migration, international governance frameworks and the challenges and solutions to address this phenomenon.

Who Are Climate Migrants?

It is important to remember that migration linked to climate and environmental factors is not a new phenomenon; people have always decided or been compelled to move away from degraded ecosystems or sudden environmental disasters. “Migrant Mother,” Dorothea Lange’s iconic photos of the American Great Depression, show a family of internal migrants from Oklahoma searching for job opportunities in California, following a prolonged period of drought that left them unable to continue farming their land in their home region.

Eight decades later, similar dynamics are at play: People choose or are obliged to move because climatic and environmental factors makes it too difficult to maintain themselves in their homes. These persons may move within their own country or abroad, temporarily or permanently.

And How Many Are They?

It is impossible to accurately estimate the number of people migrating or being displaced by slow or sudden climate events. Available data relates only to the number of people displaced following natural disasters (often made worse by climate change, but not all climate-related) and within their own country: on average, 26.4 million people yearly. However, these figures exclude those who migrate outside the borders of their country and those who move because of slow environmental degradation, such as desertification and sea level rise. Consequently, it is likely that millions more people currently choose or are forced to migrate because of environmental and climatic reasons, but are not reflected within existing statistics.

Furthermore, in the future, climate experts are expecting an increase of displaced people due to changes in climate conditions that directly threaten lives and livelihoods.

It’s impossible to accurately estimate how many people are migrating or being displaced by climate events.

What are the Characteristics of Climate Migration?

The populations affected by climate and environmental change use different mobility strategies according to the type of climate-related phenomenon they face. In the case of natural disasters, people may leave in prevention to or in response to an emergency in order to save their lives. This type of movement is often internal and temporary, as people tend to return as quickly as possible to their homes. However, large-scale disasters, such as the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, often trigger displacement that may last for years or even become permanent.

Slow environmental degradation leads to different mobility trends. In Sub-Saharan Africa, desertification threatens millions of hectares of fertile land, making it difficult to maintain agricultural livelihoods in these territories; meanwhile, small island states in the Pacific are threatened by complete disappearance due to sea level rise. In response to these phenomena, people adopt various mobility patterns, from temporary circular migration for a few months each year to permanent emigration.

In many instances of climate-related mobility, the decision to migrate stems not only from climate, but also a combination of economic and security factors, and it is difficult to determine whether these movements are forced or voluntary. How do you neatly categorize the decision of a Kenyan farmer to migrate temporarily to the city during the increasingly tough dry season to supplement his farming income, or the permanent migration of the Mongolian shepherd and his family to the capital because their herds have been destroyed by colder winters?

The International Governance of Climate Migration

Many expressions are used to refer to those moving in connection to climate and environmental change: “Environmental migrants,” “climate refugees,” “persons displaced by climate change,” etc. From a legal perspective, it is not appropriate to talk about “climate refugees,” because the legal definition of a refugee excludes reasons of climate and environmental threats. In the current political context, despite many calls from civil society actors, it is unlikely that the refugee definition will be widened to include those displaced by climate threats, as this would infer increased obligations for states.

The debate around the necessity of reinforced legal status for climate migrants is part of the broader debate of how to protect all the people migrating due to climate and environmental change, beyond the dichotomy between free-will decision or forced displacement. Here, we must remember that all migrants are protected under the human rights regime. Universal legal instruments for human rights, if properly applied, are very relevant tools to guarantee the protection of climate migrants, and the absence of a climate refugee regime should not distract from means of protection already at our disposal.

Furthermore, the Paris Agreement, universally adopted during the COP21 meetings, makes a reference to the need for states party to the agreement to “respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights … and the rights of migrants” when “taking action to address climate change.”

This reference is noteworthy considering that migration was a completely marginalized question within the climate debate a few years ago; it is a clear reflection of the heightened consciousness around climate migrants’ questions. Considering that the Paris Agreement was welcomed by all 195 states represented at COP21, this reference serves as another reminder to all states worldwide to consider the rights of migrants and human rights at large within national policies and activities to combat climate change.

For the inhabitants of Kiribati, an archipelago of islands threatened by rising sea levels, these few words might have very concrete impacts on their ability to “migrate with dignity.” For instance, an increased recognition of their rights to education might provide them with access to educational and vocational training opportunities, should they be forced to uproot to other countries.

What Next? Threats and Opportunities

Now that the issue of climate migrants has gained visibility, concrete action is needed. We must remember that the millions of individuals impacted by climate change will not necessarily want or be able to move out of affected areas; yet, it is important to emphasize that managing the migration of even a fraction of affected persons poses political challenges that we are not yet equipped to address.

First, we need to improve our understanding on the links between climate change and the movement of people in order to develop meaningful policies and programs on the ground: Who is most at risk? Where are the “hotspots”? We have some elements of the answer, but not enough is known at this stage.

Without minimizing risks or exaggerating opportunities, there is also a need to better understand how migration can support adaptation to climate change—both from a climate policy perspective and from a migration policy perspective. Concretely, this means looking at different possibilities, such as developing adaptation activities in areas with high emigration rates to enable people to migrate safely by offering new livelihood means.

In places where there is increased population pressure on the environment and shrinking natural resources, it might also be helpful to develop policies facilitating temporary and circular migration to other regions or countries to allow for households’ income diversification.

Another possibility is promoting diasporas’ engagement in adaptation projects in their countries of origin to help reduce climate-related threats for local communities.

Concrete solutions and opportunities can be developed before we face the worst-case scenario: the unmanaged movement of millions of people and its irreversible consequences.

Dina Ionesco, head of the Migration, Environment and Climate Change Division, IOM Geneva, and Eva Mach, project officer, IOM Geneva, also contributed to this piece.