Road to Economic Growth Paved with Efficient Infrastructure Investment

Construction cranes tower over the Hudson Yards large-scale redevelopment program in New York.

Photo: Don Emmert/AFP/Getty Images

Investment in infrastructure is vital: Without its upkeep and development, the costs to trade and economic competitiveness will only mount.

Working together to help channel efficient investment to infrastructure, governments and private investors alike will need to ensure that the risks are identified, managed and, where appropriate, mitigated.

Infrastructure’s Economic Benefits

Infrastructure investment is closely linked to economic output. In the short term it stimulates demand, creating employment in construction and related industries, such as manufacturing and materials. In the long term, it boosts supply, enhancing an economy’s productive capacity. For example, a new road may facilitate more trade, and it would likely support even more jobs long after the project’s completion.

This is known as the “multiplier effect,” whereby each dollar spent on infrastructure translates into greater gains for GDP. In the U.S., according to S&P Global, an additional 1 percent of real GDP spent on infrastructure could boost the economy by a factor of about 1.2. This multiplier is based on an economic analysis conducted by S&P Global economists and accounts for both the direct impact of infrastructure investment in wages paid to employees hired to build and maintain assets, as well as the indirect increase in aggregate demand spurred by the increase in disposable income. This does not include potential productivity gains in the medium to long term from well-thought-through projects. It’s been done before: Eisenhower’s great interstate highway buildout in the 1950s boosted U.S. GDP by a factor of six.

Consequences of Inaction

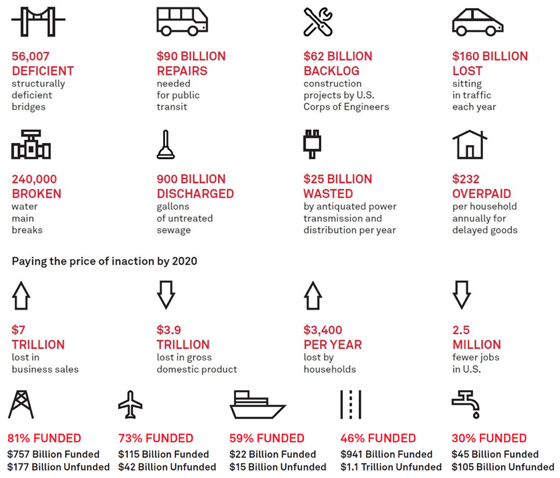

Without adequate investment in infrastructure, productivity could be limited and economic growth constrained. Modernizing the U.S. energy grid will require an extra $177 billion worth of investment—until the funds are found, antiquated power transmission and distribution infrastructure could waste around $25 billion each year. Another $160 billion is lost from vehicles sitting in traffic; the potential unpaid bill for maintenance of road networks is currently estimated at $1.1 trillion.

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), if measures aren’t taken to fund and repair the country’s aging infrastructure, business could miss out on $7 trillion in sales by 2020, with around $3.9 trillion lost to GDP. This translates into a yearly loss of $3,400 to households and 2.5 million fewer U.S. jobs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The U.S. infrastructure need in figures

Source: S&P Global Ratings, Developing U.S. Infrastructure In An Era Of Emerging Challenges: Observations From Key Sectors, June 2017

With Europe´s economic outlook looking more balanced geographically and across sectors, and with more countries posting stronger growth numbers, the spread between the fast- and slow-growing economies in the eurozone is set to narrow in the coming months. Governments’ ability to fund infrastructure projects using their own balance sheets without compromising long-term fiscal sustainability is set to increase. To help, in late 2014 the European Union launched the European Fund for Strategic Investment. This is the main execution vehicle of the Investment Plan for Europe. The European Parliament is in final negotiations to increase its capacity from an initial 21 billion euros to 33.5 billion euros.

Traditional Tapping of Private Capital

One might also look to the capital markets to foot the mounting infrastructure bill: Globally, institutional investors such as pension funds and insurers command about $90 trillion, yet they have less than 1 percent of their resources invested in infrastructure. If incentivized, investors could bring much-needed capital to the sector through debt-financing projects—without increasing governments’ debt-to-GDP ratios.

Partial privatization has traditionally brought this private capital to bear: A state-owned enterprise—perhaps an electricity transmission and distribution network—is sold under a long-term lease, overseen by an independent regulator. In May 2017, the New South Wales government in Australia sold a 50.4 percent stake of electricity distributor Endeavour Energy to a consortium of institutional, superannuation and sovereign wealth funds—freeing up AU$7.624 billion ($5.61 billion) for schools, hospitals, roads and rail networks. The state government retains a 49.6 percent interest in Endeavour Energy and will have ongoing influence over operations as a joint investor, lessor, licensor, and safety and reliability regulator. Endeavour Energy will continue to be regulated by the Australian Energy Regulator, which determines network prices.

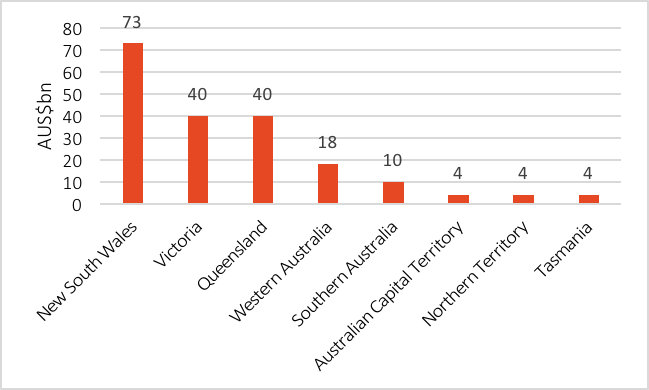

An alternative approach being increasingly considered globally is “asset recycling,” in which a greenfield project—such as a new highway—is divided into stages of development. The higher credit risk of earlier stages—in this case, the highway’s construction and ramp-up risk—is transferred to the private sector. The New South Wales government also announced in May the sale of a majority stake in the M4-M5 Link, a critical road connecting two of Sydney’s busiest highways. Along with an initial investment from the state and commonwealth governments, private-sector debt supported by toll revenue has financed the road’s development. Effectively, the state has been able to “recycle” its equity investment to help fund the final stage. As Figure 2 shows, New South Wales is the leading investor in infrastructure among Australian states and territories.

Figure 2: Gross capital investment in Australian infrastructure, 2017-2021 (AUS$bn)

Source: New South Wales government, State of the State Address, Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA), 27 July 2017

Further Tools to Finance Infrastructure

Another means of facilitating collaboration between government and private capital is the public-private partnership (P3), a procurement model where a private sector partner—normally under a long-term fixed-price contract—takes responsibility for some combination of designing, building, financing, maintaining, or operating a public infrastructure asset. Through a P3, the government entity retains ownership of the assets.

We’ve observed that P3s can put private capital to work developing, building, repairing, and maintaining the public’s significant infrastructure needs. They also allow for risks to be allocated to various parties based on their capacity and willingness to manage them. A set of bonuses and penalties are put in place under contract to incentivize the private sector to deliver a well-built and well-maintained asset on time and on budget.

The private sector provides the financing in P3s, which acts as a key incentive for optimal performance over the long term.

P3s are widely used, for projects ranging from ports, airports and high-speed railways to schools, hospitals and civic buildings (see Figure 3). They also have an established track record. In Canada alone, the model has been used for about 250 projects that together are worth over $122 billion; those that have reached financial close have saved the government an estimated $27 billion.

Figure 3: Selected public-private partnership projects rated by S&P Global Ratings

Source: S&P Global Ratings, Developing U.S. Infrastructure In An Era Of Emerging Challenges: Observations From Key Sectors, June 2017

Investors, of course, need economies of scale for cost-efficient financing of construction and operations. To attract capital to smaller assets. We’ve seen separate ventures “bundled” into one larger infrastructure entity—whether through acquisitions of smaller utility systems by larger companies, the securitization of municipal assets, or the bundling of loans in state revolving funds. In North America, courthouse, highway, school and bridge assets have been bundled in this way. In Spain last year, we saw the Vela Energy project company issue 404.4 million euros worth of bonds to refinance the construction debt for a bundle of 42 solar parks nationwide.

A sector that could especially benefit from bundling is North America’s water system. The American Water Works Association estimates the cost of modernizing the continent’s pipe and sewer facilities at $1 trillion over the next 20 years. Of the 52,000 community water systems in the U.S., more than half are characterized as “small” by the Environmental Protection Agency and may struggle to find the funds on their own.

Risks and Challenges

Infrastructure development is not without its risks. First, infrastructure investment cannot risk being fiscally unsustainable. Governments must develop assets at the lowest possible costs of capital (not just in the short term, but also across the long term, throughout the useful life of the asset), with funds allocated to those projects with the highest ratio of benefits to costs. Otherwise, higher levels of spending may simply lead to larger budget deficits. This is a particular concern for developing economies where, if the tax base is limited or tax enforcement is weak, even those public investments that could significantly boost economic growth may not reduce budgetary pressures. Yet the most advanced economies may still have little fiscal room for maneuver if—like the UK, for instance—they are already constrained by high debt-to-GDP ratios.

We have observed that a way that governments generally transfer the payment obligation is to follow the principle that users pay for infrastructure services whenever feasible. Colombia, for example—where inadequate transportation infrastructure has impeded economic performance—is currently relying on concessionaires to develop and operate 7,000 km of new toll roads. Regional and international institutional investors have provided financing based on their view that projected traffic volumes will underpin revenues.

A second risk to factor in is poor project preparation. We have observed that, ideally, it is best practice for potential projects to be carefully evaluated, planned and designed. Before committing capital, investors rely on favorable conditions and transparent insights into creditworthiness. Continued growth of the offshore wind sector, for example, relies on projects being able to overcome engineering, technological, geographical, and regulatory limitations.

Projects can face a multitude of risks: unproven technology or design, operational underperformance, exposure to adverse demand or commodity price movements in the markets, financially insecure counterparties or unfavorable regulatory environments. In the absence of appropriate mitigants, all these risks could invite the chance of default. At S&P Global Ratings, we’ve noted that in over two decades of rating project finance debt about 6.5 percent of projects default, with market risk having been the most common reason, followed by technical risk. At the same time the median recovery rate has been around 89 percent.

On a broader scale, meanwhile, efficient infrastructure markets generally depend on governments outlining both clear infrastructure needs and a long-term pipeline of projects. Just look at Spain, where the fragmentation of responsibilities for infrastructure planning across different levels of government has, in some cases, resulted in resources being invested in unfinished or unused projects, such as the construction or upgrade of barely used airports at Castellón, Ciudad Real, Huesca and Lleida before the financial crisis.

Developing the world’s infrastructure presents as many challenges as opportunities. With the risks identified, managed and appropriately mitigated, the public and private sectors could collaborate to reap the benefits of efficient investment.