Are Virtual Meetings for Shareholders and Board Members the New Normal?

While a strong case can be made to adopt regulations that allow virtual meetings, it must be done with caution. It is essential for shareholder democracy that the challenges associated with virtually held meetings be resolved to fully use their potential.

Photo: Unsplash

The global economic crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating effect on businesses worldwide. Yet, not being able to operate stores, factories or provide in-person services to clients would have been worse if companies hadn’t been able to continue holding their corporate functions.

Most key decisions — such as replacing a director or chief executive, approving finances, extending benefits to all employees during closures or filing for bankruptcy — require a formal meeting of either board members or shareholders. These meetings can produce valid decisions that bind the company only if they follow strict procedural rules mandated by law. In recent years some economies, such as Costa Rica, Vietnam and Pakistan, had started to create the legal framework for virtual meetings and voting, but it wasn’t seen as a high-priority policy. The COVID-19 pandemic changed this perception. After the pandemic subsides, virtual meetings are likely to continue and may become the new norm.

The pandemic has exposed the shortcomings of legal frameworks that do not provide for virtual board and shareholder meetings. Virtual meetings are an opportunity to enhance corporate governance and transparency by fostering more shareholder participation in a manner that proxies cannot, and by increasing communication among shareholders, management and directors. Benefits of online participation in shareholder meetings also include lowered operating costs and a reduced carbon footprint of companies.

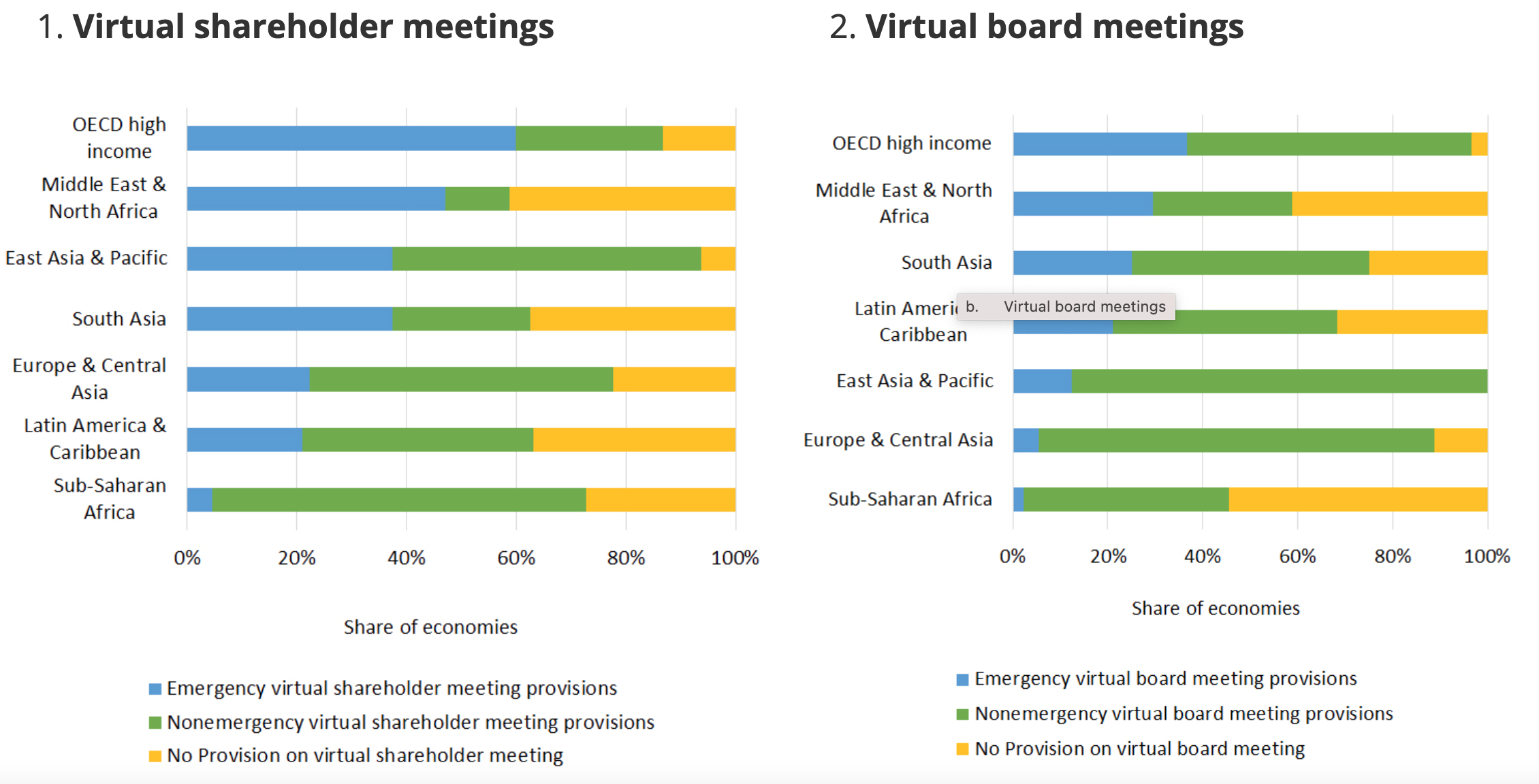

Legal Frameworks of All Economies in East Asia and the Pacific Allow for Virtual Meetings

Source: Doing Business database. Note: Sample includes 153 economies.; A cross-regional analysis highlights that there is universal adoption of virtual meetings in the legal frameworks of economies in East Asia and the Pacific region.

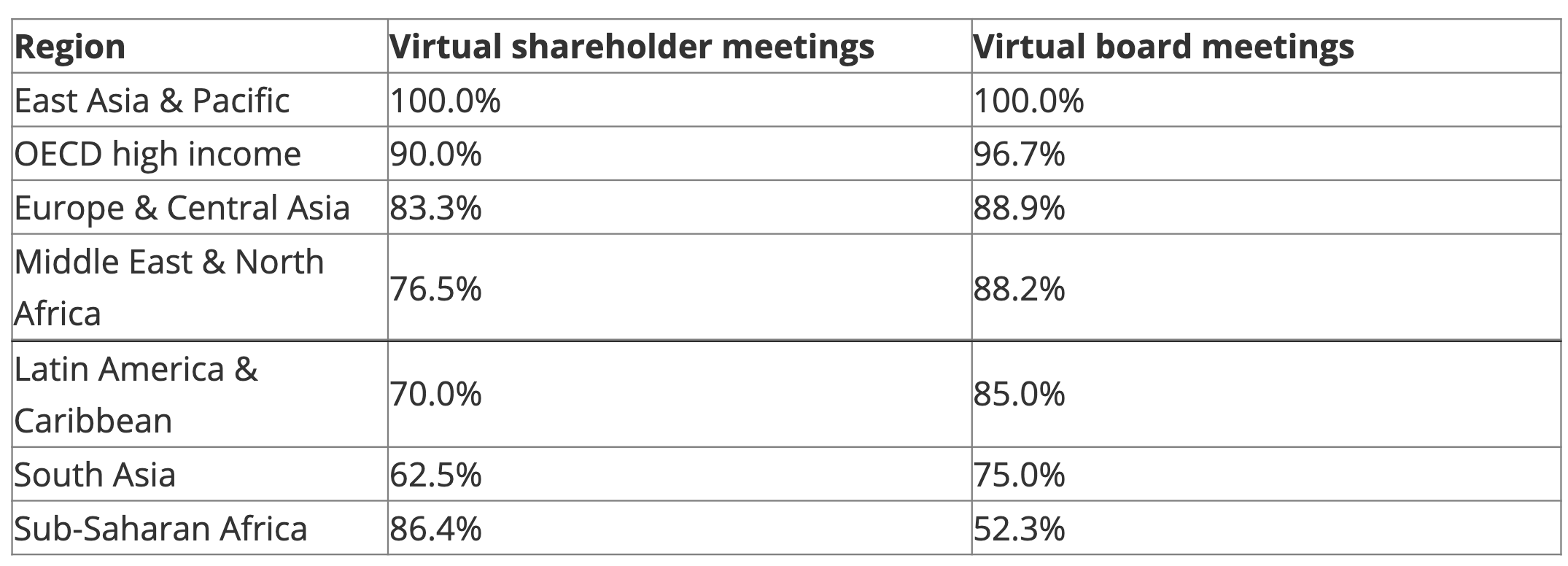

Eighty-four percent of the economies now allow virtual shareholder meetings, while 80% allow virtual board meetings, according to World Bank data collected across 153 economies in 2020. Some of these economies had existing legal frameworks well before the pandemic, while many adopted legal frameworks that allow virtual meetings as emergency measures. Most OECD high-income economies and economies in Europe and Central Asia allow for virtual meetings. The level of adoption of virtual meetings in legal frameworks in Latin America and the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia is much lower. In low-income economies, the adoption in legal frameworks is as low as 64% for shareholder meetings and 40% for board meetings.

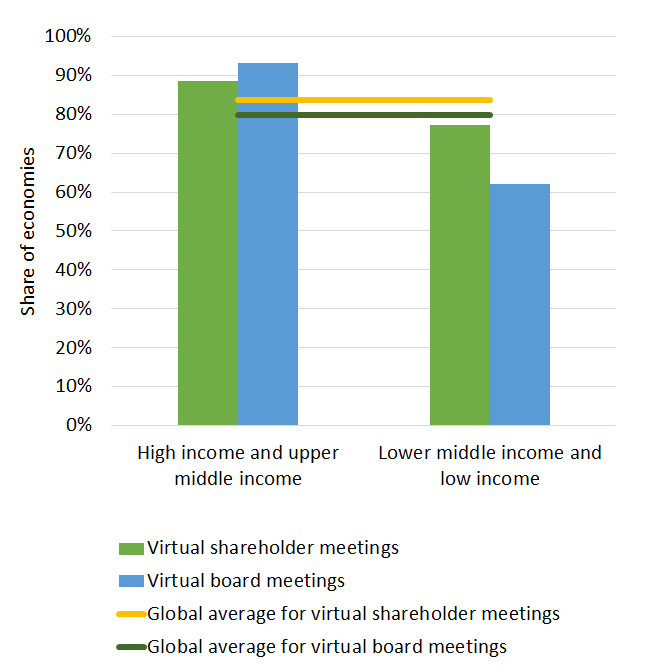

Low-Income Economies Have Lower Virtual Meeting Adoption in Their Legal Frameworks

Many more high-income and upper-middle-income economies allow for virtual meetings compared to lower-middle-income and low-income economies. However, since the onset of the pandemic, 45 economies introduced provisions through emergency legislations to expand the possibility of using electronic means and legal tools to allow companies to hold virtual shareholder meetings. Over twenty introduced such provision for board meetings. Most of these emergency measures were instituted by OECD high-income economies.

Among these, some adopted provisions on virtual meetings solely as a temporary measure in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, virtual meetings of shareholders were temporarily allowed in Australia and the United Kingdom until March 31, 2021 and are allowed in Austria, Germany and Switzerland until the end of 2021. Whether these temporary measures will be translated into mandatory regulations to encourage virtual meetings as a matter of best practice going forward remains to be seen.

OECD High-Income Economies Imposed the Most Emergency Measures

While many economies scrambled to adopt legal frameworks allowing virtual meetings to mitigate the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, 69 and 84 economies respectively had already incorporated the practice for shareholder meetings and for director meetings well before the pandemic. In Colombia, for example, Law No. 222 of 1995 allows corporate body meetings to be held virtually. Similarly, virtual shareholder meetings have been permitted in other economies, such as in South Africa since 2011, in Turkey since 2012, in Costa Rica since 2018, and in Pakistan through the Companies Act of 2017, which allows members to participate in a meeting through a video link. In Taiwan, China, attendance via tele- or videoconference is deemed as attendance in person for board and shareholder meetings. In Vietnam, a shareholder is considered to have attended and voted, when the shareholder attends and casts votes through an online meeting, electronic voting or by using another electronic medium.

In many economies, the possibility of holding virtual meetings is left to the discretion of each company. Even when permitted by law, companies must specifically include this option in their constitutional documents. However, with the recent restrictions on travel and large gatherings, companies that had not already explicitly allowed virtual meetings in their constitutional documents, could not hold a meeting and vote to amend their constitutional documents. The pandemic exposed the shortsightedness and ill-preparedness of such legislative frameworks and their inadequacy in ensuring business continuity during difficult times. To address this inadequacy, emergency legislation in Armenia, Denmark, Italy and other countries allowed companies to hold virtual meetings even without an explicit provision in their constitutional documents, making virtual meetings temporarily possible during the pandemic.

While a strong case can be made to adopt regulations that allow virtual meetings, it must be done with caution. It is essential for shareholder democracy that the challenges associated with virtually-held meetings — including proxy mechanics, voting procedures and processes for engaging with shareholders — be resolved to fully utilize the potential of virtual meetings. Companies must devise electronic solutions that replicate the face-to-face accountability of management and ensure that shareholders are not disenfranchised. For example, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange partnered with the Meeting Specialist, a service provider, to enable clients to engage with shareholders through virtual meetings. A similar platform, the e-GMS system, exists in Indonesia. A transition towards virtual meetings must make sure that the needs of all constituents are met in a fair and well-balanced manner.

This piece was originally published in World Bank Blogs.