Can Kyoto Be the Copenhagen of Asia?

Cycling trends in Kyoto provide cause for optimism. It now has close to 45 kilometers of official cycleways.

Photo: Author provided

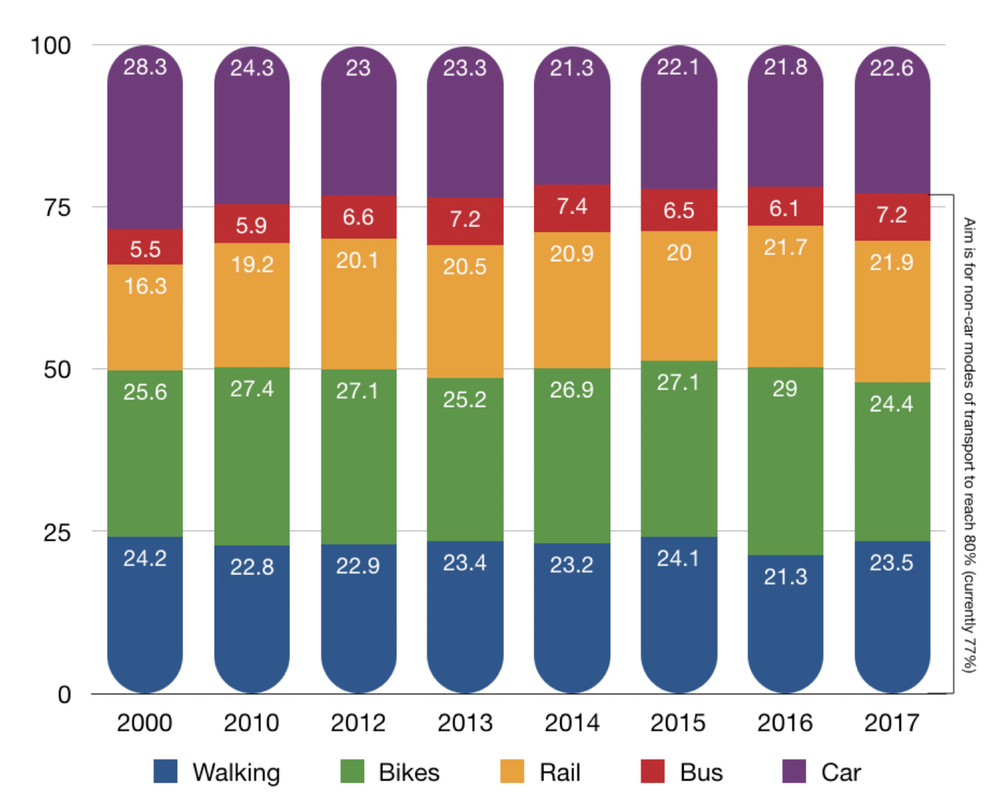

Against the backdrop of climate scientists warning that we have 12 years to cut carbon emissions to avoid disastrous climate change, Kyoto is searching for an alternative sustainable future. The Japanese city is moving away from heavy reliance on cars and toward getting around by public transport, cycling and walking. Already, more than three-quarters of personal trips in the city are not by car.

With the 2010 walkable Kyoto declaration, the city aimed to stop being a car-dominated society. Kyoto has an ambitious list of 94 projects promoting walkability.

The results so far are impressive, according to municipal government data. Use of public transport has increased significantly. Car traffic entering the city is declining year-on-year, as is use of car parking. Only 9.3 percent of tourist movements in the city were by car compared to 21 percent in 2011.

As a result of this, emissions from transportation in 2015 were 20 percent lower than 1990 levels.

Exhibit: Survey by Kyoto Municipal Government of 1,000 Citizens on Their Mode of Transport for Personal Trips

A City Made for Cycling

Kyoto is determined to improve on this. The next target is to enhance opportunities for cycling.

Cycling is the best way to see the city. Whether you are a resident or a tourist, cycling is the secret to unlocking Kyoto’s beauty and experiencing its heritage sites. An increasing number of the 50 million tourists a year are choosing to rent a bike.

Kyoto has been described as one of the ten best cities to explore by bike—it is a compact, flat city with a grid structure, making it easy to cycle and navigate.

Navigating the city by bicycle is both convenient and efficient. Bicycles provide mobility that’s accessible for a wide range of demographics, from school kids to parents with their toddlers on board to over-65s taking a short trip to the local shops.

In June 2018, one of Japan’s first shared cycle schemes, PiPPA, popped up in Kyoto with 100 bikes in 22 locations. There are plans to increase to 500 bikes in 50 locations by the end of the year. Proposals for shared electric bicycles would broaden the variety of users able to navigate the city by bike.

Mobility Policy Innovation

The mobility experience for people living in Kyoto is fascinating. That is one reason we are impressed by the March 2015 New Kyoto City Bicycle Plan, which replaced a 2010 plan.

This newer plan identifies the promotion of cycling as healthy across various realms—for the society, economy and sustainability of the city overall.

Cycling trends in Kyoto provide cause for optimism. It now has close to 45 kilometers of official cycleways. While not as big as European cycling cities like Copenhagen—which boasts 416 kilometers of cycleways—Kyoto’s network is relatively large for an Asian city.

On-street discarding of bicycles has declined twenty-sevenfold since 2001, and bicycle parking space has increased by 65 percent in the same period.

Car ownership in Kyoto is dropping year-by-year. Two in every three Kyoto residents own a bicycle, compared to one in every three owning a car.

More kids cycle to school in Kyoto than almost any other city in Japan—only Osaka is higher. Cycling is on the increase for people between the ages of 20 and 34, as well as those between 65 and 69.

Need To Educate Cyclists and Drivers

A few obstacles still stand in the way of Kyoto achieving its sustainable mobility goals.

First of all, only 33 percent of cyclists cycle on the road. Everyone else uses the pavement, meaning neither pedestrians nor cyclists feel safe.

Second, cyclists across Japan are notorious for not following rules. For example, they ignore signals, ride the opposite direction to traffic, listen to music or use their phone while cycling, cycle with a passenger on the back, cycle with an umbrella in the rain, don’t wear helmets and rarely cycle with lights at night.

In other words, Japanese cyclists are perceived to be, at times, reckless. This explains why a third of Kyoto’s cycling policies focus on improving cyclists’ manners. It also explains why the municipality introduced a mandatory bicycle insurance scheme in April 2018, which other cities may also want to do.

The Kyoto bicycle plan focuses on measures to enhance the visibility of cyclists with road markings as well as extensive educational programs for car drivers and cyclists on road etiquette.

The good news is that the number of accidents involving cyclists in the city has declined by 40 percent since 2004 and represents 20 percent of all accidents. This is close to what we find in Copenhagen.

What Else Can Kyoto Do?

A continued focus on social design and innovation is the answer to Kyoto’s mobility challenges. The city’s population is projected to shrink by 13 percent between 2010 and 2040 (reaching around 1.28 million). At the same time, the proportion of over-65s will increase significantly.

This suggests private car ownership will continue to decline by an estimated 6-10 percent per year. The bicycle ownership rate is likely to increase by 7 percent or more each year.

In this context, the focus on public transport, cycling and walking makes a great deal of sense.

But Kyoto could still do a lot more to reduce car traffic, especially in the city center. Manchester in the UK provides a useful example. It recently announced plans to invest 1.5 billion pounds ($1.9 billion) in a 1,600-kilometer cycle network.

Another model for Kyoto to follow is that of the world’s most bicycle-friendly city—Copenhagen.

Today many cities across the world are seeking to “Copenhagenize.” In the future, we want them to be able to follow Kyoto as a model of best practice for Asian city sustainability.

This piece first appeared on The Conversation.