China Slump Could Cut Global Growth to Decade Low

A worker looks on as a cargo ship is loaded at a port in China. U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports have resulted in the largest trade war in economic history between the world's top two economies.

Photo: STR/AFP/Getty Images

The present Chinese slowdown could have serious negative consequences for world growth if it intensifies. According to Oxford Economics (OE) model simulations, global growth could slow to a decade low of 2.3 percent in 2019 if Chinese growth slows sharply, and it could even drop below 2 percent if there is a slowdown in the economies of both China and the U.S.

In the case of China, the biggest impact on the global economy is going to be through a decline in its imports.

Falling Chinese Imports

The global economic growth picture is starting to resemble that seen in 2015-16, when output growth slowed down significantly. A key factor contributing to that slowdown was an abrupt weakening in China. It is something that is happening at present, too, with Chinese imports declining at the fastest pace since 2015-16.

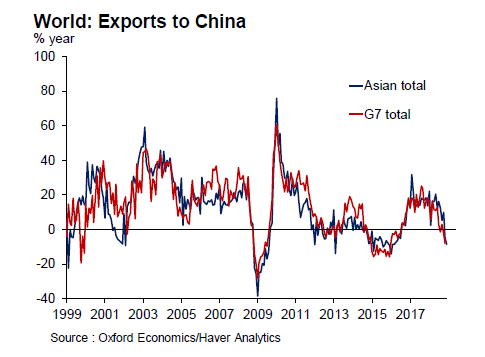

December trade data for China were much weaker than expected. In dollar terms, Chinese exports fell by 4 percent year-on-year and imports by 8 percent. Some 12 months ago, exports from both Asia and the G-7 to China were growing by nearly 20 percent year-on-year—now they are shrinking by 8 percent to 9 percent year-on-year.

While Chinese GDP growth is slowing broadly, as we expected, trade is slowing more abruptly, implying bigger negative international spillovers. With China accounting for about 10 percent of world trade—and almost 20 percent of world trade growth in the past decade—this import weakening is a significant threat to global growth.

Growing Evidence of Weaker Chinese Growth

Developments in China can slow global growth through several channels. First, weaker domestic demand growth in China reduces final goods import (consumer and investment goods) from the rest of the world. Second, weaker Chinese export growth reduces demand for imports of intermediates and raw materials from the rest of the world, a significant channel given the relatively high import content of Chinese exports.

Third, weaker Chinese demand pushes down prices of key global commodities like iron ore and copper, inflicting terms of trade losses on the exporters of these products (mostly emerging markets).

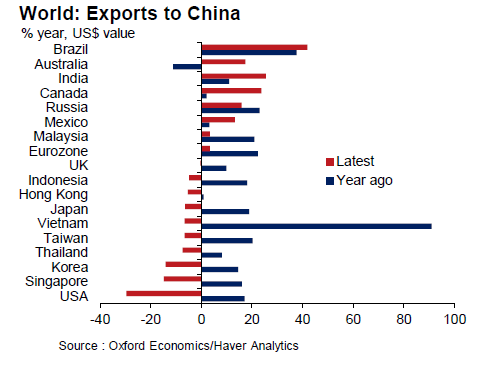

All these channels seem to be operating. As noted, import volumes fell sharply in late 2018, and some of the biggest falls were from China’s key Asian partners and component suppliers such as Singapore, Korea, Thailand and Taiwan. Some emerging markets, particularly major commodity producers, such as Russia and Saudi Arabia, will also be big losers.

China-sensitive commodity prices have also started to decline. Our index of these was down 11 percent year-on-year in January, while as recently as May 2018, it was up 16 percent year-on-year.

Separately, the impact of China’s tariff dispute with the U.S. is also becoming visible. China’s goods import from the U.S. was down 30 percent year-on-year in December. Chinese exports to the U.S., meanwhile, which were holding up earlier, have also started to slip. Survey evidence suggests this export slippage may become more pronounced in the months ahead. The Chinese export PMI, which leads actual exports by around six months, dropped in December to its lowest level since mid-2016.

There are, however, a few signs of trade diversion effects from tariffs. Notably, Brazil’s exports to China remain very strong, with Brazil stepping in to replace some U.S. agricultural exports to China.

But overall, the picture is starting to resemble that of 2015-16. A similar combination of weakening Chinese import demand and downward pressure on commodities was observed at that time as well. In that period, global trade growth ran at less than 2 percent year-on-year, non-oil commodity prices fell 20 percent and global growth dipped to a low of just 2.4 percent year-on-year.

Global Growth Could Slow to Decade Low

Our baseline forecast looks for Chinese growth to bottom out in the second quarter of 2019 but not rebound, contributing to global growth of 2.7 percent this year, down from 3 percent last year. However, there is a significant risk the outcome could be worse.

The dangers are especially acute for the industrial sector globally. Currently, world manufacturing PMI is at 51.5, consistent with world growth near OE’s 2.7 percent baseline forecast. But based on the trend in Chinese demand, this indicator could easily slip further to the 2016 low of 50.7, implying world growth of around 2.5 percent, or even to 48-49, implying declining global manufacturing output and consistent with world growth of just 1.9-2.1 percent.

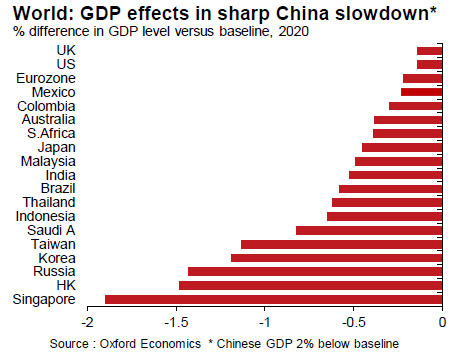

Simulations using the Oxford Global Economic Model confirm the downside risk to world growth. The model suggests that a 1 percentage point negative shock to Chinese GDP would cut global GDP by 0.2 percent in 2019-2020. A sharper fall of 2 percentage points in Chinese GDP relative to our baseline forecast would cut global GDP by around 0.5 percent by 2020.

In 2019, global growth will slip to 2.3 percent, the slowest pace since 2009. The global slowdown would be worse still in the event of a combined negative shock to Chinese and U.S. GDP. If both countries saw GDP fall by 2 percentage points relative to our baseline forecast, global GDP would be cut by 1.5 percent by 2020, with growth in 2019 at only 1.7 percent year-on-year. With the global population growing by around 1.1 percent per year, this is close to the IMF definition of a global recession.

Asian Trading Partners To Be Worst Affected

The big losers in the event of a sharp Chinese slowdown would be Asian trading partners with close industrial links to China and some emerging markets. Our modeling shows that the biggest GDP declines in the event of a 2 percentage point negative shock to Chinese GDP would be seen in Asian economies such as Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Korea. They would all register GDP levels of 1-2 percent below our baseline by 2020. Oil exporters would also lose out, as world oil prices would fall by 16 percent by 2020 in this scenario relative to our baseline.

In Asia, we see the economies of Vietnam and, to a lesser extent, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines being better-placed to benefit from trade diversion than South Korea, Japan, Singapore and Indonesia. In the short run, however, production capacity constraints will likely limit any of these benefits and will still be outweighed by the wider losses caused by the trade disruption.

The major advanced economies including the U.S. and Europe, on the other hand, would be more sheltered, with some positive offset from lower oil prices. This will likely support consumer incomes.