Europe’s Surpluses Are Funding the US Economy

An aerial view of new buses lined up for export at a port in Lianyungang, east China's Jiangsu province. China’s foreign exchange reserves have diminished from $3,800 billion dollars in 2013 to $3,000 billion dollars today.

Photo: STR/AFP/Getty Images

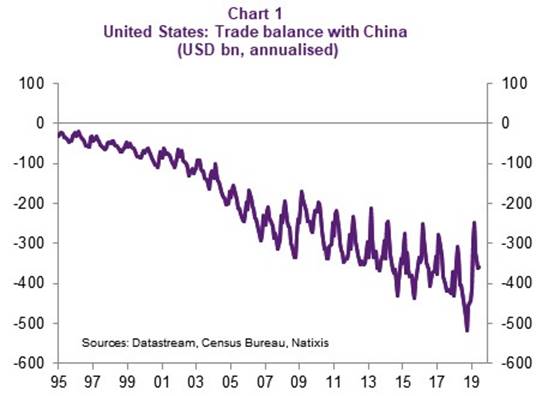

From 1990 to 2013, there was an implicit pact between the United States and China: The United States bought large quantities of cheap Chinese products, which boosted its consumption and living standards and generated a growing trade deficit with China (Chart 1).

In return, China partly financed the United States federal budget by accumulating foreign exchange reserves in dollars, particularly in the form of U.S. Treasuries (China’s holdings of U.S. Treasuries reached $1300 billion in 2012). This pact was good for both countries: The United States could consume more; China could produce more.

Europe Has Replaced China in Financing the United States

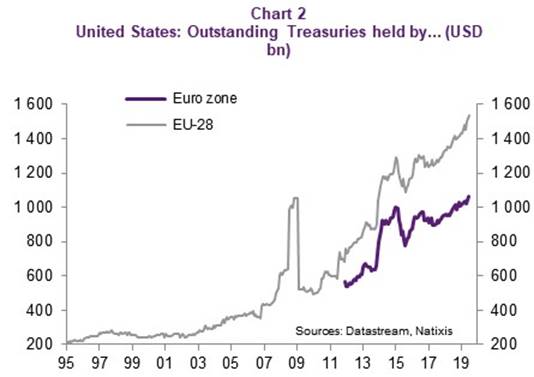

From 2013, China, faced with capital outflows, stopped accumulating foreign exchange reserves, including the United States. China’s foreign exchange reserves have since diminished from $3,800 billion dollars in 2013 to $3,000 billion dollars today.

Herein lies part of the origin of the trade tensions between the United States and China: The U.S. trade deficit with China has continued to grow, but China no longer finances the United States.

Instead, Europe — the eurozone in particular — has replaced China in financing the United States (Chart 2). But instead of being the fruit of a pact between the United States and the eurozone, this is a result of the eurozone’s dysfunction.

The Eurozone’s Dysfunction

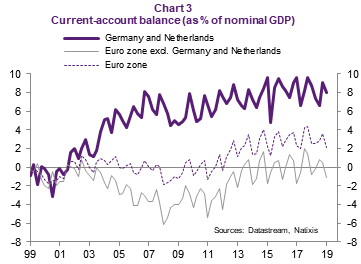

From 2012, in the aftermath of the eurozone crisis (2010-2013), eurozone countries with savings surpluses (namely Germany, the Netherlands) lost confidence in the solvency of the other countries — both their governments and banks — and stopped lending to them. Instead, they lent to the rest of the world outside the eurozone.

Since 2012, Germany and the Netherlands’ external surpluses have no longer been the counterpart of external deficits in other eurozone countries, but rather the counterpart of an external surplus for the eurozone (between 3% and 4% of GDP). This demonstrates that Germany and the Netherlands’ savings surpluses are no longer invested inside the eurozone (Chart 3).

The fact that the eurozone has financed the United States since 2013 results from the eurozone’s dysfunction and the ending of capital mobility between those countries with a savings surplus and those with a savings shortfall.

A Return to Normality Would Be a Shock for the US

If the eurozone’s functionality were to return to normal, the United States would be in great difficulty, because Germany and the Netherlands’ savings surpluses would, once again, be lent to other eurozone countries. In these other EU countries, there would be an increase in investment, where it has fallen significantly, which would absorb Germany and the Netherlands’ excess savings. As a result, these savings would no longer be available to finance the U.S. external deficit.

With neither China nor the eurozone financing it, the United States could then be forced to reduce its external deficit by saving more and investing less, potentially leading to a recession in the United States. In short, it is because of the eurozone’s dysfunction that the United States is currently able to run twin deficits (fiscal and external) without difficulty.