Experts Are Worried about 2019. What Are the Top Issues on Their Radar?

A Chinese paramilitary police officer stands guard as a plane carrying the U.S. Secretary of State arrives at Beijing Capital International Airport in China. Experts are worried about increasing risk in geopolitical and economic areas.

Photo: Mark Schiefelbein/AFP/Getty Images

The international political and economic tensions that dominated 2018 show few signs of easing in 2019—and business and governmental leaders are increasingly worried about the risks and spillover effects these conflicts will bring.

Respondents to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Perception Survey (GRPS)—a sample composed of experts across business, academia, government, and a range of other organization types—had a pessimistic outlook for international relations and cooperation on the global stage in 2019. One part of the survey asked respondents to assess whether the risks associated with a set of issues would increase or decrease in 2019 compared to the previous year. The top three issues where most respondents believed risks would increase all pertained to geopolitical issues; the top ten was dominated by risks concerning geopolitical and economic conflicts as well. Further data and research from the Pew Research Center, the International Monetary Fund, the U.S. Department of Defense and a range of other sources validate these concerns.

These top geoeconomic and geopolitical concerns identified by the respondents can be roughly grouped into three categories:

- Friction between major powers and the erosion of international economic and security agreements

- Domestic political concerns, including polarization, nativism, and populism

- A lack of global coordination around climate change mitigation

Economic and Political Frictions Are a Top Concern

The top concern for respondents of the GRPS was “economic confrontations/frictions between major powers.” Ninety-one percent of them believed risk in that area was likely to increase in 2019, beating out the second-highest issue—the related issue of the erosion of multilateral trade agreements—by 3 points.

These respondents aren’t alone in thinking this. A new International Monetary Fund report revised estimates for global economic growth downward by 0.2 percentage points, identifying the trade negotiations around Brexit and the trade war between China and the U.S. as key factors in the revision. And the Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index reached record highs in December of 2018.

The political and economic risks identified as key problem areas by GRPS respondents are intertwined, and the erosion of multilateral agreements and norms in the world of trade are likely to have spillover effects beyond the immediate economic impacts: One recent paper found that the implementation of trade agreements increased synchronicity in voting in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Trade, the authors concluded after an analysis of trade agreements and UNGA votes, “can encourage future leaders to follow globally accepted norms and values … [and] has a positive effect on the political stability between the countries.”

This kind of increased synchronicity would be a welcome change of pace for respondents to the GRPS, 85 percent of whom ranked “political confrontations/frictions between major powers” as an area where risk was likely to increase in 2019. In fact, the Global Risks Report (GRR) notes that although conflict-related deaths have fallen dramatically since the highs of the mid-twentieth century, the number of global conflicts has increased in the past few years. “While not mass death conflicts, these are clearly a source of emotional and psychological distress for huge numbers of people in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia,” write the report’s authors.

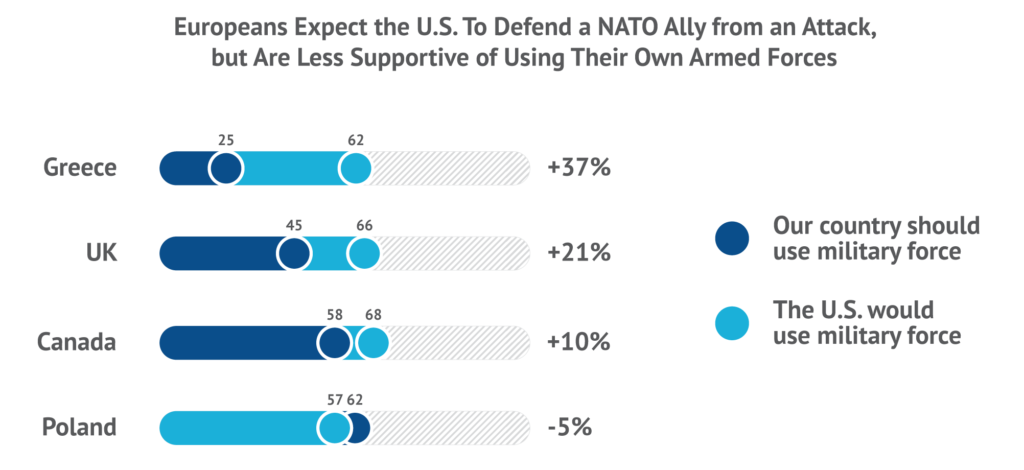

The past few years have shown changing sentiment toward international security arrangements by leaders of major powers—ranging from renewed interest in maintaining these arrangements to complete disregard of the rules and norms outlined therein. This was reflected in the GRPS: Respondents were not confident in the strength of collective security alliances in 2019, with 73 percent answering that risk around this issue would increase in 2019. Hard data may bear out this unease. A July 2018 survey by the Pew Research Center found that, although NATO was viewed favorably by citizens of NATO member states, in the case of conflict, most respondents supported U.S. military intervention in defense of an ally, but not the involvement of their own country in the conflict—defeating the point of a collective security agreement.

Populism, Nativism, and Polarization

The next category of concern for respondents of the GRPS concerned polarization and the rise of nativist and populist sentiment. Inequality and public anger against elites also registered as significant related concerns, with 63 and 59 percent of respondents, respectively, believing that risks related to these issues would increase in 2019. One of the fears outlined in the GRR was that this strand of domestic pressure, coupled with weak governance and increasing risks of global conflict, might lead to significant political instability and unpredictable knock-on effects.

One of the key statistics raised by the GRR is the increasing prevalence of anger. In Gallup’s 2018 Global Emotions Report, the polling service’s Negative Experience Index saw the continuation of a trend of increasing reported negative experience; the index of positive experiences, on the other hand, remained mostly stable, registering only a small dip.

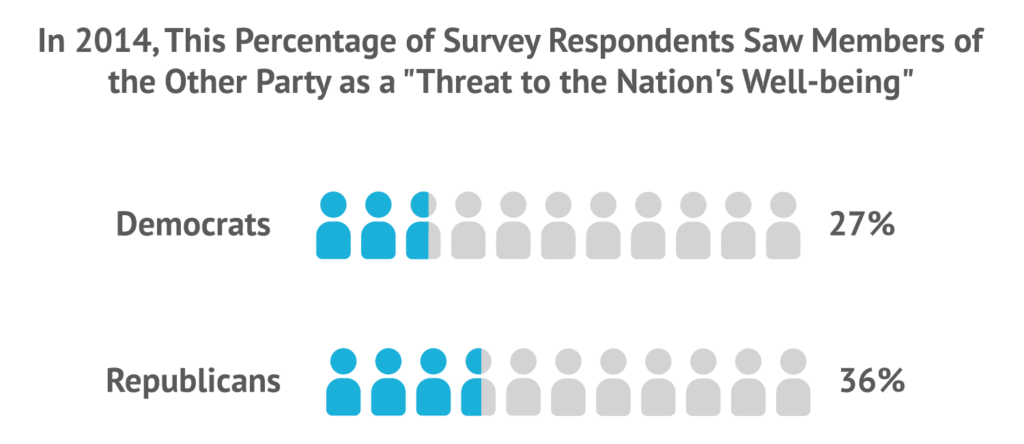

This trend can be observed through the lens of politics in the U.S. “In the United States, public opinion researchers note that where opposing political groups previously expressed frustration with each other, they now express fear and anger,” write the authors of the GRR. “In one survey, almost a third of respondents reported having stopped talking to a family member or friend over the 2016 election.” In fact, in 2014, a Pew Research Center survey found that 27 percent of Democrats saw the Republican Party as “a threat to the well-being of the country”; 36 percent of Republicans thought the same of the Democratic Party. Another recent survey found that 44 percent of respondents expected relations between the two parties to get worse in the coming year.

Climate Disruption Is an Increasingly Visible Source of Risk

Late last year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that the international community had 12 years to stall the rise of atmospheric temperature or else face irreversible negative changes. This warning did not go unnoticed: 64 percent of GRPS respondents viewed “the erosion of global policy coordination on climate change” as an area where risk would increase in 2019.

The risks are wide-reaching. Physical infrastructure, ranging from roads to ports, and digital infrastructure, including the Internet, could be impacted by rising sea levels. Other forms of climate change-related natural disasters could lead to population displacement: This kind of population movement, write the authors of the GRR, “could result in heightened strain on food and water supplies and in increased societal, economic and even security pressures.”

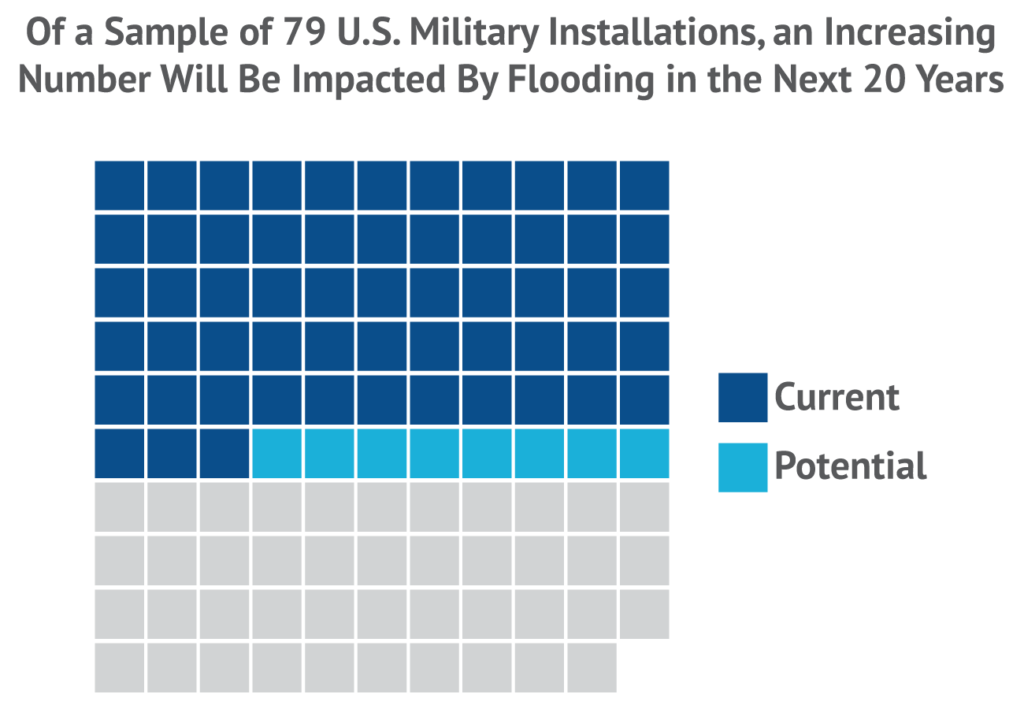

A recent report by the U.S. Department of Defense made clear the impact of climate change on its military installations—which, in turn, could have spillover effects on the capabilities and responsiveness of the U.S. military. According to the report, roughly two-thirds of the installations named in the report are vulnerable to flooding in the next 20 years; more than one-half is vulnerable to droughts; approximately one-half is vulnerable to wildfires.

The impacts of these vulnerabilities and climate change more broadly range from increasing costs of repair and maintenance to increased expenditures related to humanitarian assistance administered by the military.