Health Care Workers Are Moving to Gig Work in Record Numbers

Nearly one-fifth of hospitals in the U.S. have critical staffing shortages, as burned out health care workers leave medicine.

Photo: Unsplash

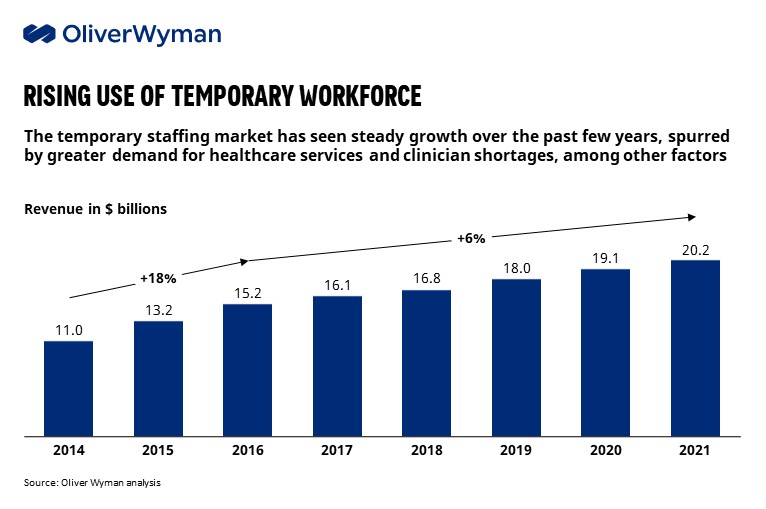

COVID-19 has battered the health care workforce. Historically known for their resilience, the pandemic has left doctors, nurses and other front-line workers not just exhausted, but bitter, traumatized and questioning their passion and commitment to a calling they once loved. In search of greater work-life balance and mental well-being, many are considering major changes to their work-life, from moving to gig work to leaving the profession altogether, quantified by the overall growth of ~6% per annum of the temporary staffing market.

This burnout has had a severe impact across the health care continuum. In January 2022, nearly one-fifth of hospitals in the U.S. claimed “critical” staffing shortages, while nearly 60% of nursing homes nationwide were forced to limit admissions in December 2021 due to a lack of staff. Health care executives, equally exhausted after spending over two years managing a mounting series of COVID driven crises, are aggressively trying to address workforce burnout with traditional monetary levers (e.g., pay raises and bonuses). These actions have had material downstream affects: a ~16% increase in labor operating expenses has contributed to a median operating margin ~10% lower than pre-pandemic norms, with over one-third of U.S. hospitals operating in the red by late 2021.

Staffing shortages have a significant impact on patient safety, too, including greater reliance on workarounds, which can lead to near misses. In fact, ECRI named staffing shortages as its top patient safety concern for 2022.

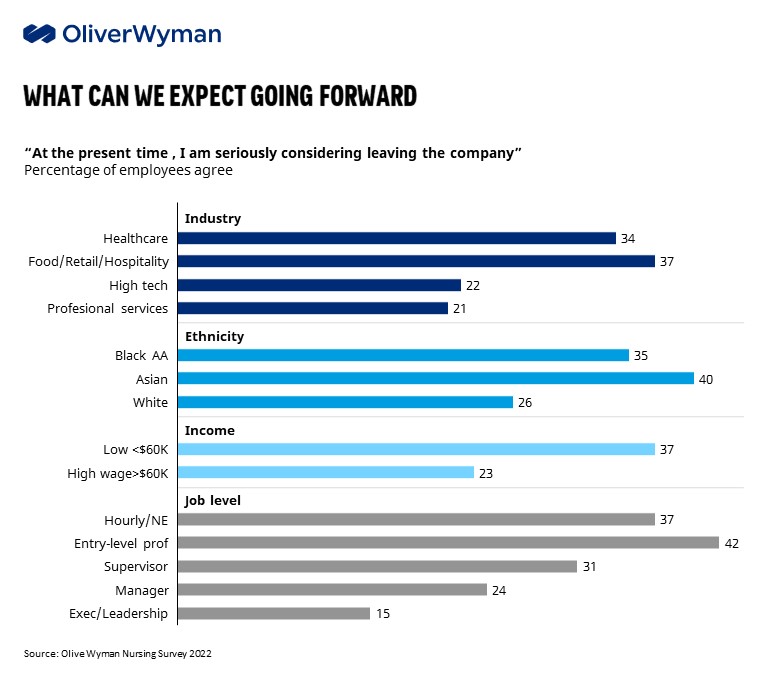

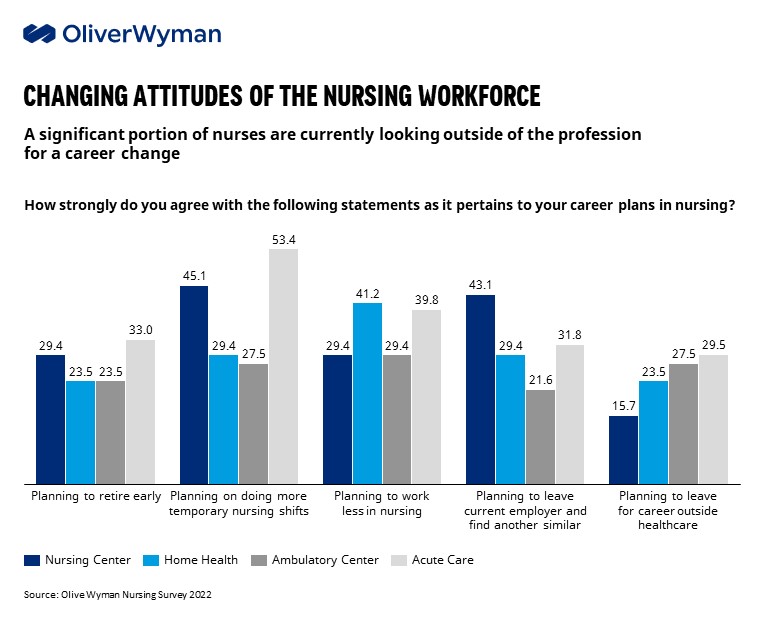

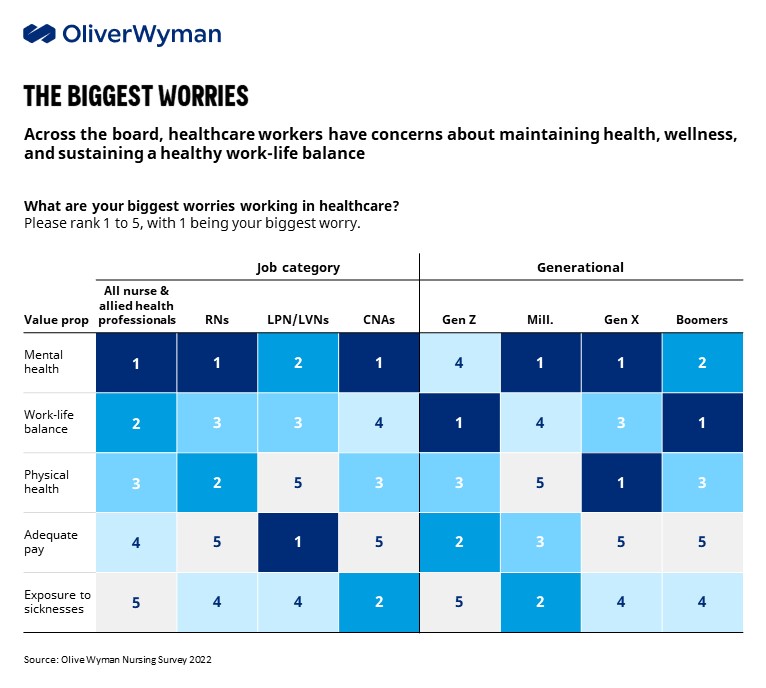

Oliver Wyman research suggests that traditional and more transactional levers (such as pay hikes) do not address the root cause of burnout and can be “too little, too late” for affected workers. Nursing staff responding to a recent Oliver Wyman survey ranked attention to their mental health and a focus on work-life balance as their top worries for working in health care rather than adequate pay or benefits. Despite the lucrative financial opportunities available to most health care workers in today’s market, our recent survey of nursing and allied health professionals suggested 20% to 30% have accelerated retirement plans, with 50% to 60% planning to change their career in some way, including a significant portion (15% to 30%) planning to pursue a career outside of health care all together.

Our survey illuminated an alternative path forward for smart and self-reflective leaders who are willing to address the core issues that matter most to this workforce. This requires abandoning the traditional HR-centric approach in favor of shifting an organization’s culture and strategy to reflect the new realities of today’s workforce. Organizations that transform care delivery, build flexibility into formerly rigid jobs, and demonstrate a clear investment into the emotional well-being of their employees will be the ones that successfully build back better. We have to understand what has driven the current staffing crisis, and what can be done to bring back workers who have left, as well as retaining those who have stayed.

Front-Line Workers Want More Control Over Their Own Career

A core component of this change (one that Oliver Wyman expects to persist) is the shift to gig labor, with our recent Nursing Survey revealing 1400% growth in the number of nurses moving to gig models — traveler, day-agency and other types of per diem — since the start of the pandemic. Nurses are seeking greater control over their schedules and the greater flexibility that comes with shifting to gig work — a model where nurses can control their work-life balance and prioritize the volume, duration, location, and timing of shifts they take. Beyond greater job flexibility and higher wages, nurses tend to perceive that they are better taken care of by staffing agencies that do not “push” them to work over time. “My employer didn’t have my back during the pandemic. At least my staffing company has my back and I have control over when I work,” one nurse told us.

This trend has resulted in a complex feedback loop, where nurses who have stayed in traditional staff roles can feel frustration and resentment that what they perceive as loyalty to their institutions is rewarded with nothing but lower wages, worse shift schedules, and generally poorer work-lives than their colleagues who have shifted to gig-work. “Every week I would look over at the nurse next to me, making three times as much while doing the exact same job,” said an ICU nurse who made the shift to travel contracts during the pandemic. “Now I can take a month off in between contracts, control where I live and work, and get paid more for the privilege.”

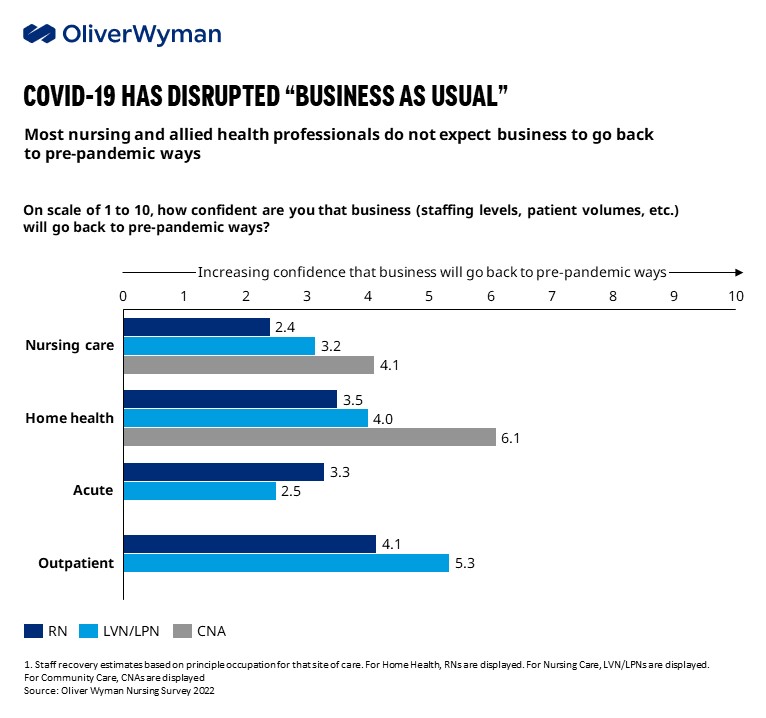

There’s every indication that these trendlines will continue. Few respondents to Oliver Wyman’s nursing study expect their work life, including staffing levels, to stabilize anytime soon. In fact, demand for health care workers rose +105%, +164%, and +60% across nursing care, community care, and home health respectively compared to pre-pandemic levels, with elevated demand projected to persist through at least 2024.

Supervisors and Leaders Need to ‘Have the Back’ of Their Workforce

As mentioned above, mental health, physical health and work-life balance ranked higher than pay when nursing respondents were asked about their greatest concerns about working in health care. They cited work-life balance, emotional demands and flexible scheduling as key drivers in why they would consider leaving their organization.

During interviews with more than 100 nursing professionals, the overwhelming majority noted that their employers have historically shown little regard for these factors. “I left my full-time role because the responsibilities kept piling up and I just wasn’t getting support from the hospital,” said one critical care nurse. The nursing workforce unsurprisingly desires connection and a supervisor who “has their back” and will advocate for them, but the culture of many health care organizations has failed them.

This concern is persistent across generations, with both Baby Boomers and Gen Z ranking work-life balance as their top concern working in health care. While the Millennials and Gen X were more concerned with mental health, these are simply two sides of the same coin: Addressing both requires viewing health care workers as whole people, not just cogs in an uncaring machine of a hospital.

Money Is a Driver, but Workers Need Connection

While pay showed up as a key criteria when considering potential employers across all segments in our survey, it is important to understand that compensation alone is not enough. Health care professionals want “fair compensation.” Unpacking this language, we learned that this means the ability to cover everyday needs, ensure their family is cared for and adequately plan for the next five years. Nursing professionals want to feel that their employers care and are interested in helping them achieve their goals. It’s not just about getting paid at a high rate, but also about being supported — e.g., an employer helping to pay bills or student loans, support continuing education, plan for retirement, and other services that aren’t necessarily conveyed through a number on a paystub.

The health care workforce is in crisis, and with it the health care system overall. Health care executives need to take truly transformative steps to save it. They can continually ask their workforces what matters to them and take action on what employees say is consequential. They can upend traditional approaches to recruitment, use apps to facilitate more flexible scheduling options, invest in more remote work options and strategically use gig workers. Health care organizations can change their cultures at a foundational level and change the relationships they have with their nurses, doctors, and other front-line workers who sacrificed so much throughout this pandemic. What’s at stake is the very health of our communities.

John Rizzo, Engagement Manager, HLS Private Capital Oliver Wyman; Kevin Wistehuff, Engagement Manager, HLS Private Capital, Oliver Wyman; and Noah Piwonka, Associate, HLS Private Capital, Oliver Wyman contributed to this article.