Is China Pivoting Toward the Middle East?

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) invites Saudi Arabia's King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (L) to view an honor guard during a welcoming ceremony inside the Great Hall of the People on March 16, 2017 in Beijing, China.

Photo: Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

At this year’s World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared his intention to host the second Belt and Road Summit for international cooperation, to which most countries from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have been invited.

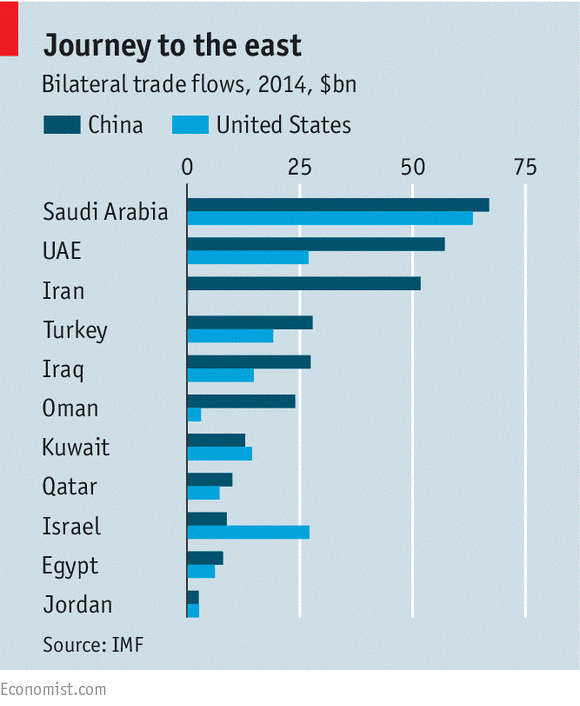

This follows China’s first Arab Policy Paper, outlining the government’s vision for an enhanced relationship with the countries of the Middle East. The document indubitably reflects the Middle East’s soaring importance in Beijing’s eyes and could very well be a harbinger of its future plans. Indeed, in the decade to 2014, trade flows between the two sides have surged by 600 percent.

But does this development indicate a Chinese pivot to the region? And what are the key issues around the intensifying relationship between China and the countries of the MENA region throughout the past decade?

Need for Oil

In 2015, China overtook the U.S. as the world’s top importer of crude oil. Of the 6.2 million barrels per day (bpd) that China currently imports, more than half are extracted in the MENA region. This has turned China into the top destination for several countries’ exports, including both Saudi Arabia and Iran. Underpinned by solid growth, and as a mounting number of its citizens acquire automobiles, its thirst for crude oil is not likely to be quenched anytime soon. In fact, the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects its imports from the MENA region to double by 2035. The region is believed to sit on half of the world’s proven petroleum reserves. As a consequence, China’s interest in its stability is only likely to grow.

One Belt, One Road

Unveiled by President Xi in October 2013, the “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) initiative will direct considerable Chinese financial resources toward infrastructure projects across 60 countries. In particular, the economic belt component would aim to integrate countries that lie along the original “Silk Road,” running through Central Asia, the Middle East, and all the way to Europe.

Through OBOR, China is striving to achieve three objectives. On one hand, it hopes to stimulate the economies of trading partners to prop up demand for its exports. By establishing a land route for its wares, it would also seek to rebalance its economy from the port cities on its east coast toward its more deprived western and southern provinces. At the same time, such a trade route would reduce its dependency on the Strait of Malacca for its international trade, through which flows an estimated 80 percent of its oil imports. China would thus be at the mercy of a maritime blockade, should tensions escalate over the South China Sea, for instance, grinding its economy to a halt. At the heart of three continents, the MENA region would therefore constitute an indispensable element of that strategy.

For this purpose, China has endowed the New Silk Road Fund (NSRF) with $40 billion, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) with $100 billion, with a mandate to invest in partner countries’ infrastructure projects. AIIB’s board includes—among other countries—the region’s two rival heavyweights, Iran and Saudi Arabia. In 2016, the AIIB provided $1.7 billion in loans, including $300 million of financing to expand Oman’s Duqm Port and to lay the groundwork for the country’s first railway system. Given the relatively long return horizon for Chinese investors, their experience in investing in areas with high political risk, and MENA’s immense need for long-term investment in infrastructure, this first loan could be the forerunner of many more to come.

Chinese Expertise at Work

As oil prices are expected to remain subdued, MENA countries will be compelled to wean their populations off the costly subsidies bestowed upon them in the past. In particular, energy and fuel subsidies will not only affect the state of their public finances as their revenues from energy proceeds dwindle, but are also regressive in nature, which means they benefit the well-off more than they do the poor. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that energy subsidies were worth 22 percent of regional public revenue and 8.6 percent of regional GDP in 2011.

To manage this transition, governments will need to adopt more efficient systems for energy generation and distribution. China has become the world’s largest producer of solar electricity generation equipment. Given its geographic position, the MENA states would be particularly well-suited to benefit from Chinese technology and know-how in the field. With the leaps that technology has made in recent years, and the significant decrease in its cost, it will possibly become competitive even in the absence of subsidies in sunny regions like MENA.

Additionally, being one of a handful of countries that have not grown weary of nuclear power plants in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan, China is on track to triple its nuclear generation capacity by 2020. With interest rising from MENA countries, in particular in the Persian Gulf, a mutually beneficial partnership could very well emerge in this domain as well. Having recently abandoned 103 coal power plants, China’s leadership is increasingly focused on ameliorating its environmental conditions by becoming a world leader in renewable energy.

Likewise, according to the World Bank’s Global Financial Inclusion Database, MENA has the highest regional percentage of a population that is without access to financial services, with more than 85 million unbanked adults. At the forefront of financial technology (fintech), with trailblazing services offered by the likes of Alipay, Baidu, and WeChat, Chinese expertise has the potential to become a gamechanger in helping the region’s poor bypass conventional banking altogether.

A Deepening Relationship

Having complementary interests in the fields of energy, renewables, infrastructure, trade, and possibly technology, the cooperation between China and the MENA countries is only likely to deepen in the years to come. Still, with yet more room to grow, this burgeoning relationship has the potential to play a decisive role in their quest for economic transformation and diversification. Chinese participation in the World Economic Forum on the Middle East and North Africa on May 19-21 in Jordan—as well as MENA countries’ participation in the upcoming Annual Meeting of the New Champions in Dalian in June—will be watched closely for any telling signs of increased mutual engagement between the two sides.

This piece first appeared on the World Economic Forum Agenda blog.