One Belt, One Road: How Will Partners Profit?

Journalists take pictures outside the venue of a summit at the Belt and Road Forum on May 15, 2017 in Beijing, China. China’s trade, investment and construction activity in One Belt, One Road countries is on the rise. Its bilateral trade with 65 countries along the OBOR was $962 billion in 2016.

Photo: Thomas Peter – Pool/Getty Images

China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative has been the subject of awe and skepticism alike. There are those who believe it will support the long-term growth of partner economies through the development of infrastructure and better connectivity, while others have concerns.

The initiative can bring benefits if managed well, particularly in some of the least developed parts of the world; but at the same time, China needs to avoid its engagement with recipient countries becoming unbalanced. For example, it should avoid that its manufacturing exports crowd out domestic production and result in trade deficits that may lead to economic and/or political tensions in countries party to the initiative.

Large-Scale Impact

Since its launch four years ago, OBOR has gradually gained traction with new projects and financing coming on stream, such as the flagship 418-kilometer rail link with Laos and the $46 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. More than 100 countries and international organizations have joined the initiative, with nearly 50 having signed intergovernmental cooperation agreements with China on joint construction.

While there is no official data on the total number/value of OBOR projects, the China Development Bank said in 2015 that it had reserved $890 billion for over 900 projects (in transportation, energy, resources and other sectors) across 60 countries. Meanwhile, the Export-Import Bank of China said in early 2016 that it had started financing over 1,000 projects in 49 OBOR countries. Most of the existing projects are concentrated in South Asia, Southeast Asia and Central Asia, given their geographical proximity and close relationship with China, but there are investments in East Africa and Southeast Europe also.

While the impact of the plan is hard to quantify at this stage, China’s trade, investment and construction activity in OBOR countries is on the rise. Its bilateral trade with 65 countries along the OBOR was $962 billion in 2016, one quarter of the total. The share of exports going to the OBOR region has grown steadily to 28 percent in 2016, nearly 12 percentage points higher than the share of exports to the EU and 10 percentage points higher than that to the U.S.

The share of China’s imports coming from OBOR countries has fallen in recent years (measured in U.S. dollars). While this is in part because of the fall in commodity prices, it also points to possible problems with China’s economic engagement with the OBOR countries—that China’s manufacturing exports crowd out domestic production and result in trade deficits.

According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, nonfinancial outward direct investment to OBOR countries totaled $14.5 billion last year, slightly less than in 2015, when China’s overall overseas direct investment (ODI)—including nonfinancial ODI—to OBOR countries rose twice as fast as total ODI. Also, the value of new engineering contracts signed by Chinese companies in the OBOR region has increased steadily—it rose 36 percent year-on-year in 2016.

Moreover, China established 56 economic and trade cooperation zones in 20 countries along the route by end-2016, with investment exceeding $18 billion.

China Replacing Multilaterals?

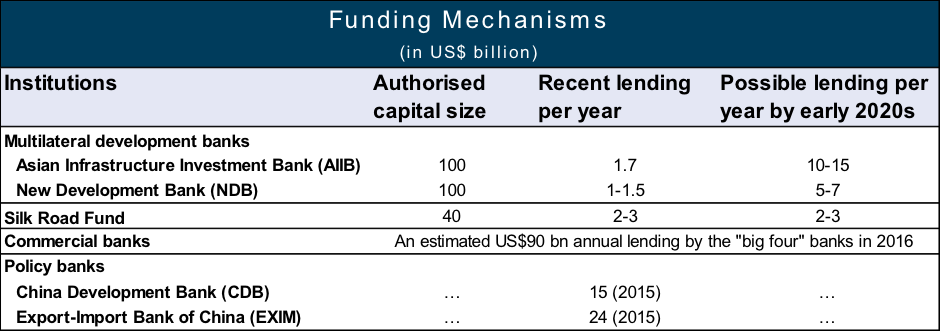

To provide development funding for the OBOR, China launched three new initiatives recently: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Silk Road Fund, with a total initial capital base of $240 billion.

While these new institutions have started to play an active role in project financing, most of the funding for OBOR projects actually comes from China’s policy banks and commercial banks. Based on the annual reports and public announcements by the “big-four” state-owned banks, we estimate that together they have extended $90 billion loans to the OBOR countries in 2016, while China’s policy banks are also major lenders.

Thus, bilateral financing from China’s commercial and policy banks dwarfs multilateral financing, and we expect that to remain the case in the future.

Nevertheless, even the combined annual financing flows likely to be generated by these and other international multilateral institutions (such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank) are modest when compared to infrastructure spending needs in the vast OBOR region—the ADB estimates the annual infrastructure investment needs at $1.7 trillion until 2030, for example.

Thus, the OBOR scheme is unlikely to “crowd out” other international development cooperation.

Likely Impact Outside China

Responding to criticism that OBOR seems a solo act by China, President Xi Jinping instead describes it as a “chorus.” This language is meant to alleviate concerns abroad that China will dominate the initiative and projects.

We expect OBOR to support long-term growth and development in the economies involved. If OBOR is managed well, better infrastructure should facilitate trade and investment, create new market demand and contribute to global development. OBOR-generated infrastructure may, in particular, benefit some poorer countries, including in Central and South Asia, which have especially large infrastructure gaps and often have difficulties financing new projects.

There is clearly much room for developing infrastructure in OBOR countries. The level and quality of logistics and infrastructure is generally low, compared to developed countries. Infrastructure deficiencies mean high transport costs, which hamper market access, cross-border trade and economic development.

If China’s own experience is any guide, better infrastructure and greater regional connectivity should improve access of OBOR countries to the global market, better leverage comparative advantages and underpin long-term development.

OBOR infrastructure could further boost growth in an already rapidly growing part of the world. GDP growth in OBOR countries averaged 4.2 percent in 2014-16, compared to the global average of 2.6 percent. We estimate that the region contributed 68 percent of global GDP growth in 2016, with Asia’s contribution (including China) well above 50 percent.

We estimate that by 2050 the OBOR region will contribute 80 percent of global GDP growth, with China’s share remaining broadly stable at around 40 percent and that of the rest of Asia doubling from the current 15 percent to over 30 percent.

This fairly constructive projection of the OBOR region is subject to downside risks, including global trade protectionism and, domestically, supply side constraints. OBOR infrastructure, as well as regional trade and investment collaboration, reduce those downside risks.

A previously published piece on BRINK Asia by Tianjie delved into the implications of the OBOR for China’s economy and global standing.