Regional Cooperation Key to Surviving the Next Asian Financial Crisis

This picture taken on February 3, 2015 shows a general view of the Tokyo Tower and the skyline of central Tokyo.

Photo: Yoshikazu Tsuno/AFP/Getty Images

When Asia was hit by its regional financial crisis 20 years ago, Asian policymakers were quick to call for regional solutions to what was perceived to be a common problem: Asian countries’ dependence on foreign finance. Prominent political figures and scholars argued for a greater regional focus of monetary and economic policies, suggesting the introduction of currency baskets modeled on trade patterns, financial structures, and even Asian currency units akin to the European Currency Unit, the euro’s predecessor.

Important progress was made in the years after the crisis to put regional financial systems on a more stable footing. Countries established the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization, a region-wide network of swap agreements, and the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office, a surveillance unit accompanying the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization. The Asian Bond Markets Initiative supported the development of local currency bond markets in an effort to prevent the renewed buildup of currency and maturity mismatches on regional balance sheets—two major factors behind the 1997 crisis. In recent years, however, Asian financial cooperation has received less attention. What explains this development?

Three Key Factors

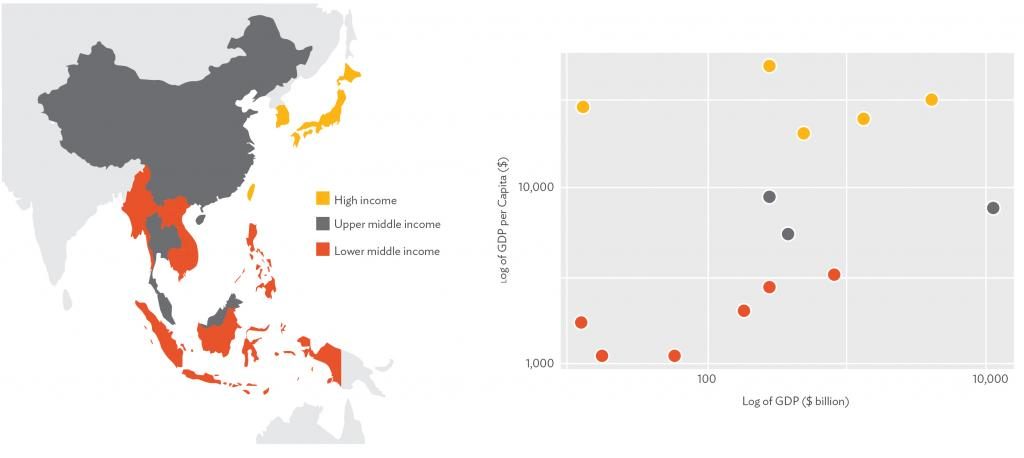

Part of it is economics. The world has changed since the days of the “East Asian miracle.” East Asian economies have matured and trade relations have evolved. Policymakers in the region now pay much greater attention to relying on domestic consumption to drive economic growth and to overcoming the middle-income trap. All the while, income levels in regional economies remain very different (Figure 1), which is a challenge for any type of economic policy coordination, not only monetary policy. The crisis of the European Economic and Monetary Union has further dampened expectations for any big leaps in regional financial cooperation, while the withdrawal of the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) has shaken up regional trade relations in unexpected ways.

Figure 1: East Asian Economies Remain Diverse

GDP = gross domestic product.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, income groups according to World Bank classification.

Efforts toward regional trade facilitation and monetary cooperation continue, however, as policymakers of several Asian economies have expressed interest in reviving the TPP without U.S. participation. China’s One Belt, One Road initiative has also received greater attention alongside the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a proposed free-trade agreement between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and its “plus six” members (Australia, the People’s Republic of China, India, Japan, the Republic of Korea, and New Zealand). At the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) recent 50th Annual Meeting in Yokohama, Japan, ASEAN+3 finance ministers and central bank governors further outlined the “Yokohama Vision,” which reaffirms their commitment to regional financial cooperation.

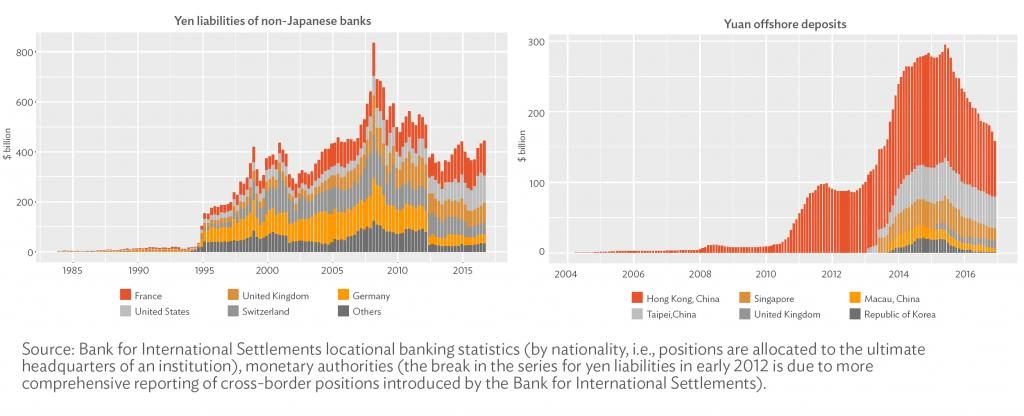

Another factor is currency. Regional financial cooperation requires strong regional currencies and capital markets, and developing these takes time. While capital accounts have been largely liberalized and local currency bond markets have grown, East Asian currencies still mostly circulate within the boundaries of their respective economies (Figure 2). Even the internationalization of the yuan has slowed in recent months, although there remains potential for the Chinese currency to play a more important international role following its inclusion in the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights.

In this area, too, policymakers have not stood still. Regional central banks, such as the People’s Bank of China and the Bank of Japan, have expanded bilateral swap networks and other initiatives within and beyond the region. An important example includes the Bank of Japan’s cross-border collateral arrangements, which allow financial institutions in partner economies to obtain local currency funds by pledging Japanese government securities held in Japan. Policymakers also continue to attach great importance to expanding local currency bond markets and regulatory strengthening. The ADB-supported ASEAN+3 Credit Guarantee and Investment Facility, which provides guarantees on local currency-denominated bonds issued by companies in Asia, plays a central role here. The renewed momentum for regional cooperation built in Yokohama might also provide new impetus for further developing regional credit rating systems, a long-standing priority of the Asian Bond Markets Initiative and a key ingredient for deepening markets for local-currency-denominated assets.

Figure 2: Offshore Markets for Japanese Yen and Chinese Yuan

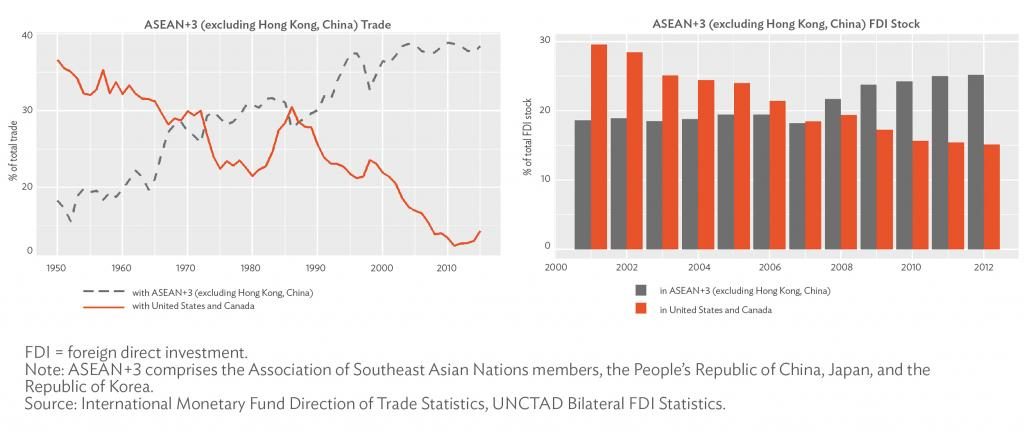

Finally, East Asian cooperation, financial or otherwise, has often been driven by real economic developments. Monetary and financial policies have typically followed the needs of trade and supply chain integration, while long-term infrastructure projects have often been tied to local currency bonds, which in turn contributed to market deepening in these currencies. As regional trade and investment flows continue to expand (Figure 3), so will the opportunities for financial cooperation.

Figure 3: Trade and Foreign Direct Investment Continue to Shift toward East Asia

As Asia’s infrastructure needs remain significant, real economic developments will continue to shape policies in the region. In particular, the recent establishment of the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) is likely to expand the availability of regional finance for infrastructure. The memorandum of understanding signed by ADB President Takehiko Nakao and AIIB President Liqun Jin in early 2016 will open up new avenues for intraregional cooperation and shared learning. Cooperation between ADB and the AIIB, and growing local-currency bond markets, will take Asia one step closer to closing its funding gap for infrastructure investment.

The growth of intraregional linkages within East Asia has been an organic process, and regional policy has been most successful when it has focused on and supported bottom-up initiatives. Past cooperation in East Asia addressed areas where interests among countries clearly overlapped and where there was potential for win-win outcomes. Building on this practical approach is key to successful financial cooperation in East Asia.

This piece first appeared on the Development Asia website, an initiative of Asian Development Bank.