The Gender Gap in Retirement Savings in ASEAN

Women return from lunch break at Raffles Place in Singapore's financial district. The significant impact of the gender retirement savings gap is still underestimated.

Photo: Roslan Rahman/AFP/Getty Images

This is the final story in a weeklong series on ASEAN.

Rising life expectancy and declining birth rates are resulting in an aging population as well as a widening retirement savings adequacy gap in the ASEAN economies. With the low coverage of mandatory pension schemes and the weakening family-based support for retirement income, the region’s older people are facing serious challenges in maintaining a reasonable standard of living after retirement.

Given that women tend to have longer life expectancies and lower participation in the workforce than men in general, women’s financial well-being is at greater risk after retirement, particularly for those in low-income jobs.

While the issue of gender pay inequality is gradually being recognized by businesses and societies in general, the significant impact of the gender retirement savings gap, a long-term consequence of the pay difference as well as the unequal sharing of care responsibilities and paid work between couples, is still underestimated.

A recent report by Tsao Foundation’s International Longevity Centre Singapore and Mercer and Marsh McLennan Companies’ Asia Pacific Risk Center delves into this gap and explores potential solutions to enhance the financial security of women in four ASEAN economies—Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand—and in Hong Kong.

Key Findings

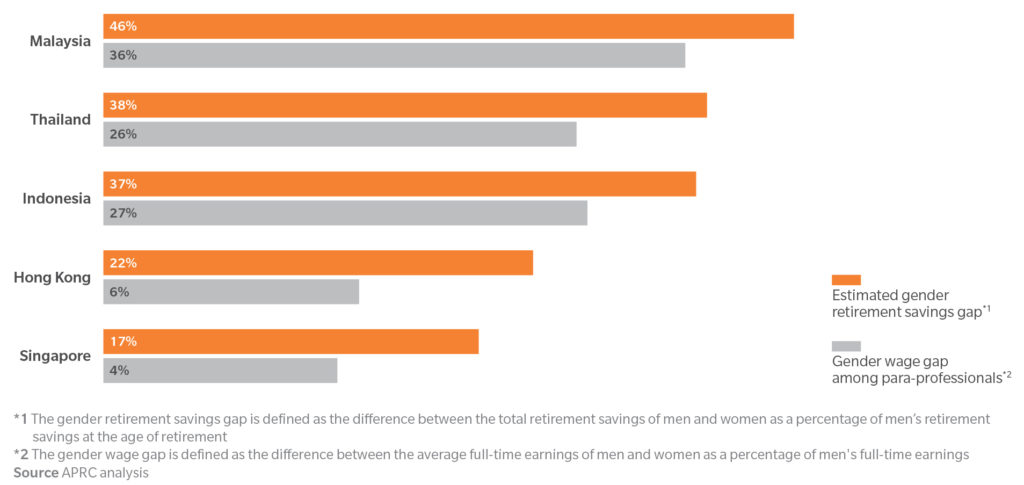

For people in low-income jobs, such as clerks and receptionists, in the markets studied, women on average have about 32 percent lower savings—both on the personal and mandatory national levels—than men at the age of retirement. The gap varies significantly among different markets, ranging from as high as 46 percent and 37 percent in Malaysia and Thailand, respectively, to 17 percent and 22 percent in Singapore and Hong Kong. Moreover, compared to the gender wage gap across the markets in our study, the gender retirement savings gap is significantly wider.

Exhibit 1: Gender Retirement Savings Gap by Country

Source: Marsh McLennan Asia Pacific Risk Center and Tsao Foundation, Gender Retirement Savings Gap for Low-Income Professionals

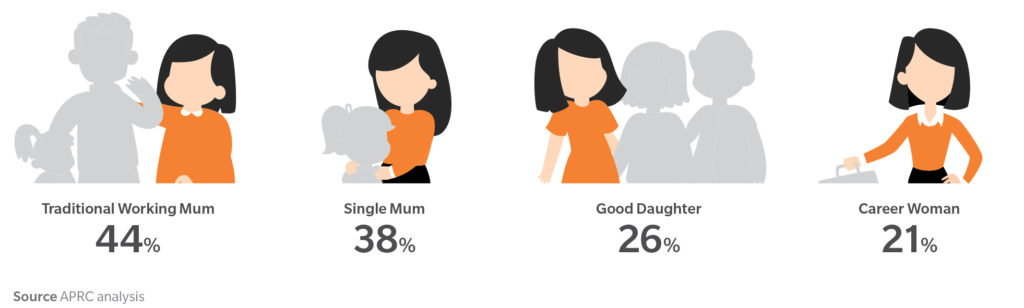

The study also compares the total retirement savings of different female archetypes with that of the male archetype—“The Family Man”—to evaluate the gender retirement savings gap among different profiles of women. The findings show that the “Traditional Working Mom”—who takes time off from her career to care for her children—has the lowest savings at retirement, about 44 percent less than the “The Family Man.” This is followed by the “Single Mom”—who works full time her entire life but bears the brunt of full family expenses—with a gender retirement savings gap of about 38 percent.

Exhibit 2: Gender Retirement Savings Gap by Archetype

Source: Marsh McLennan Asia Pacific Risk Center and Tsao Foundation, Gender Retirement Savings Gap for Low-Income Professionals

Without adequate retirement savings, one common challenge that all women archetypes face is the rising medical expenditures driven by medical inflation. The upward trend of health care costs has a large impact on the elderly, since people tend to have a higher rate of health care use as they age.

Moreover, as shown in the 2017 Mercer Medical Benefit Effectiveness Survey Singapore report, women constitute 74 percent of medical claimants of neoplasm—the disease that has the highest average cost per hospitalization—indicating that women in particular need to be better prepared for medical inflation. In addition, with longer life expectancies than their husbands, women are also more likely to live alone and hence incur higher long-term care costs. This is worsened for women who don’t have others to care for them in old age.

Why Do Women Have Less Savings?

Gender wage gap. The retirement savings gap is partly driven by the wage inequality between men and women. According to the Mercer Total Remuneration Survey, men’s base salary in paraprofessional roles is about 25 percent higher than women’s in Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia and about 5 percent higher in Singapore and Hong Kong.

Short working lives. A shorter working period for women also contributes to the gender retirement savings gap. Compared to men, women are more likely to take career breaks or engage in part-time employment to fulfill domestic responsibilities. In addition, women also tend to leave the workforce earlier to care for family members. With fewer years of full-time employment, women’s workplace savings are significantly lower.

Financial literacy gender gap. The lack of adequate financial literacy is increasingly contributing to a lower wealth level of low-income women near retirement. Even in a more advanced country like Singapore, only slightly more than half (52 percent) of women are considered financially literate, about 15 percent lower than their male counterparts. In addition, women are more risk-averse when it comes to investment; women are 62 percent more likely than men to invest in a defensive fund with a lower expected level of growth. As a result, women are not only growing their savings at a slower rate, but some may not even have the mindset of building up their retirement savings when they are young.

Risk of automation. Technological advances, such as automation, are creating new jobs while leading to traditional job losses. And roles that do not require a high level of skill sets face a disproportionately greater threat of displacement from automation. Given the higher level of female participation in this field in Asia, automation is posing an increasing risk for women with lower skills.

Enhancing Women’s Financial Security: A Multistakeholder Undertaking

Failure to address the gender retirement savings gap could cause long-term costs for businesses and society. Therefore, closing the gender retirement savings gap needs to be a multistakeholder undertaking.

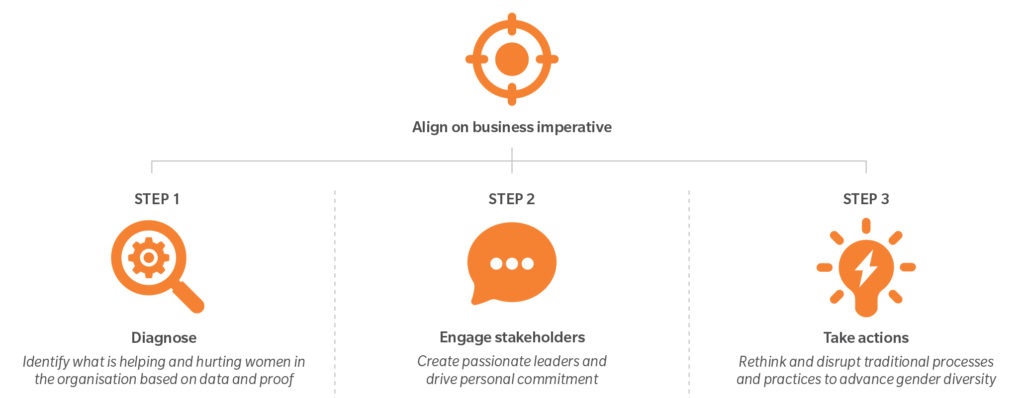

Employers. Employers should play an active role in ensuring female employees’ financial security. It is not only key to improve a company’s talent attraction and retention, but also crucial in protecting a company’s productivity, especially with an increasingly aging and shrinking workforce. To achieve this goal, a robust diversity and inclusion strategy needs to be created.

Exhibit 3: Framework for Advancing Women in the Organization

Source: Marsh McLennan Asia Pacific Risk Center and Tsao Foundation, Gender Retirement Savings Gap for Low-Income Professionals

Government. The gender retirement savings gap is a long-term consequence of unequal sharing of care responsibilities and paid work among couples. Therefore, governments may consider initiating policies wherein pension systems recognize the time spent in socially relevant activities and encourage more equal sharing of caregiving work among couples. Additionally, another critical role that government could play is enhancing support for informal caregivers. For example, to encourage caregivers to continue their careers, affordable child care services, as well as elderly care services, need to be further developed, because the high costs of child care or elderly care usually pose a barrier to women’s employment.

Individuals and society. Reducing the retirement savings gap is also the responsibility of women themselves. With longer life expectancies and growing health care costs, women need to put aside considerably more in savings than men to ensure a financially secured retirement. To achieve this goal, women should first change the mindset of solely relying on their partners for financial security. Rather, it’s important for women to understand how to manage their finances independently through attending financial literacy courses or through consulting financial professionals and to take active steps to save and invest in their incomes no matter how much they earn.

Closing the Gap

There are stark imbalances between women’s need to save and ability to do so, as well as a significant gap in the level of financial security experienced by women compared to men.

Closing the gap is a shared responsibility of employers, government and individuals and should be a priority in light of the aging population, medical inflation and the displacement of jobs due to automation.

Employers can play a key role by implementing pay equity processes as well as conducting diagnostics to gain a better understanding of the savings and investment behaviors of men and women and the factors that influence those patterns.

Governments, for their part, can work toward offering a conducive environment for creating fair workplace policies and retirement plans that cater to women’s health and financial circumstances.

And finally, individuals should take action to educate themselves on the policies and programs available that best fit their personal situation.