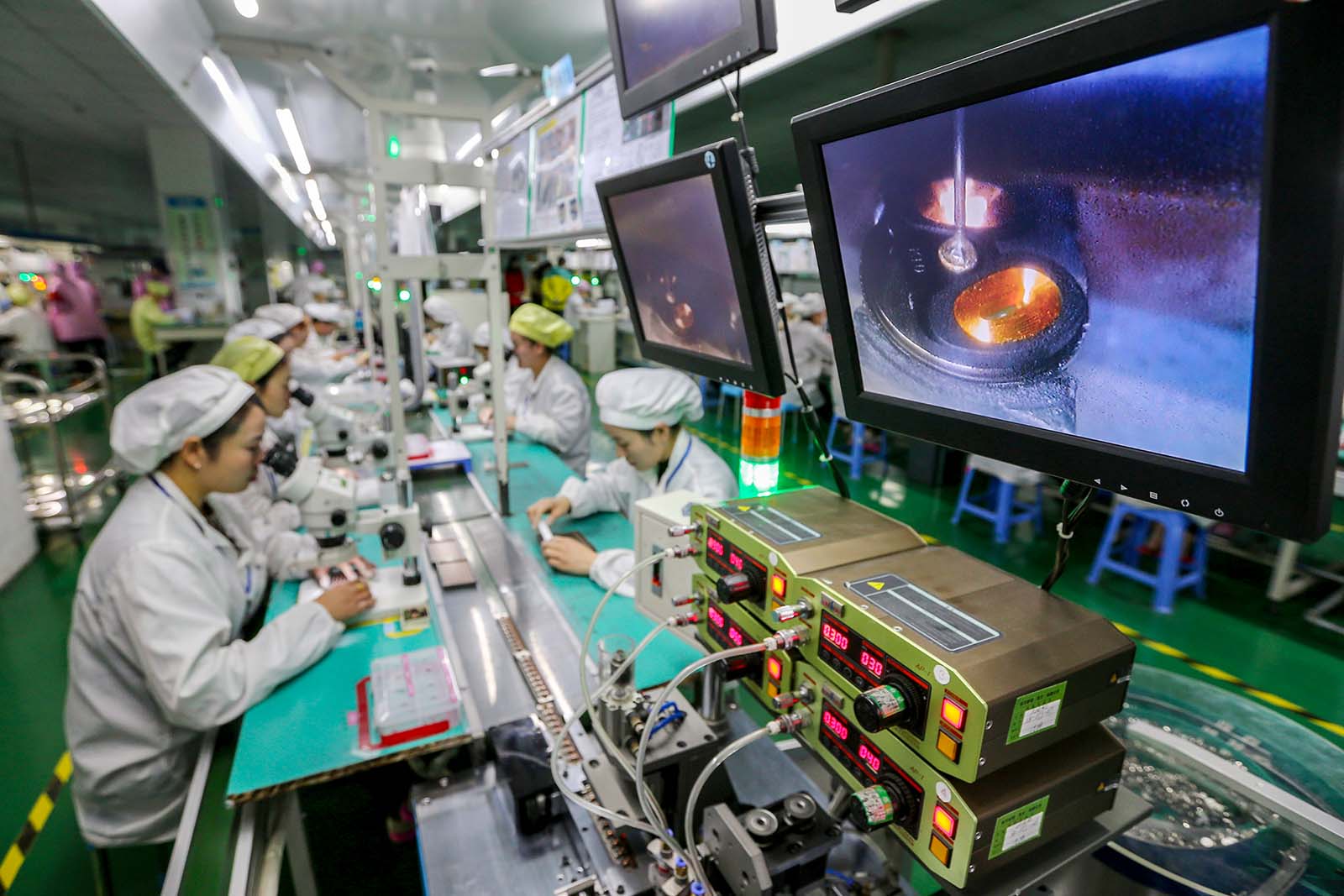

Employees work on micro and special motors for mobile phones at a factory in China's Anhui province. Among the regional emerging economies, China is a leader in terms of taking steps to get more value out of global value chains.

Photo: STR/AFP/Getty Images

In the face of increasing protectionism, it is imperative that economies start ascending global value chains (GVCs) to remain competitive. Structural reforms are key elements in the transition that less-developed countries need to make. In the midst of already existing challenges, there are pressures arising from the Fourth Industrial Revolution in the form of AI and automation. In light of such developments, Asian economies need to start adapting quicker—and several countries, including China, are already leading by example.

John West, the executive director of Asian Century Institute and author of the recent book Asian Century … on a Knife-Edge spoke to BRINK Asia about how countries in the region can climb GVCs and eventually become GVC leaders.

BRINK Asia: How can Asian businesses get more out of value chains considering that production chains are changing?

John West: At this stage, apart from leading Japanese and Korean companies like Toyota and Samsung, most Asian businesses are in a subordinate role in GVCs, which are led by businesses in advanced countries. This means they are largely undertaking low value-added functions like assembling electronics, sewing clothing, or providing low-cost sites for motor vehicle manufacture. The risk is that they can get stuck in such low value-added functions. This may already be happening in countries like Malaysia and Thailand, which seem to be caught in middle-income traps.

To get more value out of GVCs—and ultimately become GVC leaders, not followers—Asian businesses need to strengthen their business and technological sophistication and innovation capacities, as well as their human capital. Countries in the region need to build greater trust with GVC leaders—Western multinational companies—who are in constant fear of intellectual property theft. Progress in these areas would enable Asian countries to undertake higher value-added activities and ultimately become GVC leaders.

BRINK Asia: In terms of structural reforms or initiatives, what can countries in the region learn from China?

Mr. West: Among the regional emerging economies, China has done the most in terms of taking steps to get more value out of GVCs.

For example, China has been ramping up its spending on R&D dramatically, with R&D’s contribution averaging 20 percent of annual growth between 2003 and 2013. China now also accounts for about 20 percent of global spending on R&D, not too far behind the 27 percent of U.S. This means that China is unquestionably on the road to becoming a science and technology powerhouse.

China has also become a major outward investor, with flows averaging $120 billion a year over the past few years. This investment is now increasingly targeting Western companies with technology, know-how and brands to enable it to climb further up the GVC.

BRINK Asia: But many advanced countries have raised concerns over the degree of openness in the Chinese market. Are they valid?

Mr. West: Yes, China has many restrictions on market access, such as for its semiconductor market, for which it has great ambitions. The “Made in China 2025” initiative is targeting 40 percent self-sufficiency in semiconductors by 2020, for example, rising to 70 percent by 2025. This would reduce Chinese imports of U.S. semiconductors by half in 10 years and ultimately eliminate them entirely within 20 years. Not surprisingly, this initiative has provoked the ire of the current U.S. administration and is a major target of the U.S.’s proposed protectionist measures.

Technology will have major impacts on Asia’s GVCs and provide governments with a chance to implement major policy change.

All things considered, China’s efforts to get better value out of Asia’s GVCs are very impressive and will no doubt help it climb further up the GVC. But the real lesson from the world’s innovation leaders like Switzerland, Sweden, the UK and the U.S. is that other ingredients are also necessary. Open economies are necessary to boost competition as well as cooperation between different companies and countries.

BRINK Asia: Speaking about structural reforms, how big a challenge is the increasing prevalence of new technological trends such as AI and automation for Asia, and how can the region cope?

Mr. West: Technology will have major impacts on the region’s GVCs and provide governments with an opportunity to implement major policy changes as it sweeps through our economies, societies and politics. The digital economy has the potential to improve productivity, lower production costs, and raise demand. But as more repetitive and routine tasks are replaced by machines, automation and robots, what is necessary is for governments to invest more seriously in education, skills and training, and lifelong learning, both to optimize the benefits of digitization and to enable displaced workers to find new employment.

More fundamentally, for those economies that have based their attractiveness on the availability of low-cost labor, digitization may pose a strategic threat. As digital technologies and the Fourth Industrial Revolution reduce costs in advanced economies and further reduce the role of labor in manufacturing, there is less incentive to offshore production to low-wage economies. The contraction of GVCs in this manner can become a major challenge for Asian countries.

Indeed, there has been mounting evidence that in recent years GVCs have been contracting with more multinational enterprises “onshoring” production. Looking ahead, Asia’s emerging economies must aim to base their development on smart labor and advanced technology rather than just cheap labor.

BRINK Asia: How much of a challenge is stunted social development for Asian businesses?

Mr. West: Rising income inequality results in higher poverty and a smaller middle class. This means that local markets—and therefore business opportunities—are weaker, because citizens have less spending power. Inequality can lower future investments in education and health, thereby compromising future economic prospects.

Asia’s development is also stunted because, although places like Singapore, Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have some of the world’s best education systems, others like India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand have poor education systems. According to the OECD, for example, many students in Thailand aren’t acquiring basic skills required for their success, and more than half of Indonesian fifteen-year-olds do not master basic skills in reading and mathematics. Similarly, according to the Asian Development Bank, Indian children had the lowest number of schooling years out of 12 leading countries from developing Asia.

These countries are on the wrong side of the education divide and have a great deal of work to do before human capital can drive innovation and creativity, and to adapt to the challenges of digitization, which again links back to the changing nature of work, given the technological advances that are being made.

Another divide which is stunting Asia’s social development is the digital divide. One picture of Asia is that of tech-savvy young populations who are developing and moving faster than the rest of the world, especially in Japan and Korea. However, the overall reality is that more than half of Asia’s four billion citizens still do not use the Internet. While 47 percent of the population in China is not online, about 70 percent of India’s population does not use the Internet. It’s a similar situation across other populous Asian economies such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar and others.

Needless to say, the costs of this digital divide are enormous, not just for the individuals who are not connected to the Internet, but for businesses that are looking for customers and competent employees. And these costs will only increase as digitization sweeps through our economies and societies, leaving too many people behind.