Latin America’s Social Unrest Complicates Foreign Investment

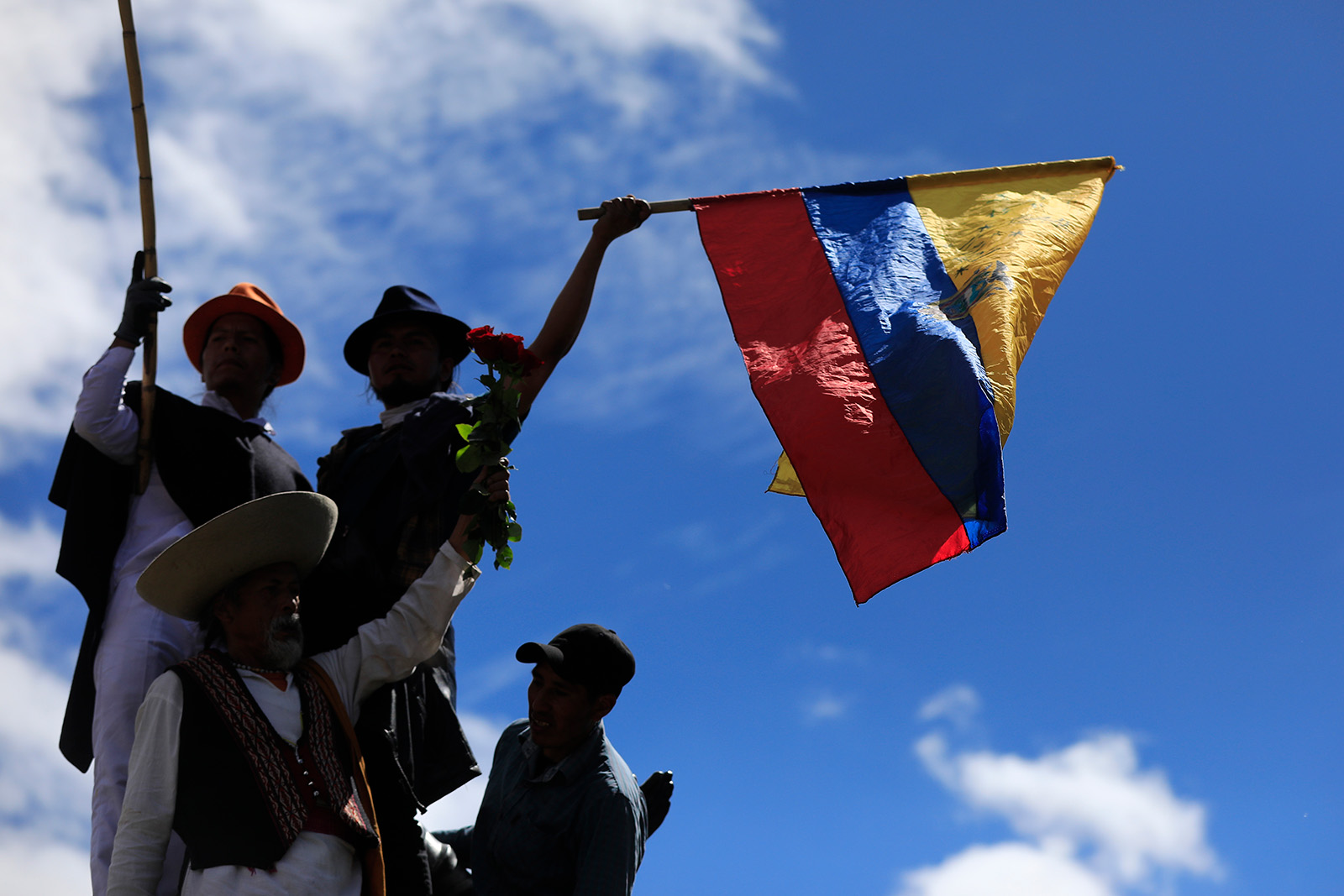

Indigenous demonstrators stand in the Ecuadorian Episcopal Conference during protests against right-wing president Guillermo Lasso on June 30, 2022, in Quito, Ecuador. The Ecuadorean indigenous community has been leading protests over the country against the high cost of living since June 13.

Photo: Franklin Jacome/Agencia Press South/Getty Images

Social unrest is increasing the world over, but Latin Americans are taking to the street faster and more violently than most other countries in the world. Recent unrest in Ecuador and Panama are just two examples of widespread street protests venting fury at their governments due to each country’s political and economic difficulties.

Small communities across Latin America are increasingly rising up against large commercial investment projects that are perceived to be damaging to the environment or infringing on territorial rights of minority and indigenous groups. So what are national governments doing to protect investors and keep businesses open? Not much, it turns out.

Driven by Local Issues

Two recently elected presidents — Gabriel Boric in Chile and Gustavo Petro in Colombia — were even the architects of street protests before launching their campaigns.

Much of the unrest is about local issues. As the economic environment worsens due to higher fuel and food prices, governments are doing little to step in to mediate the rising conflicts, even though such passiveness may well impact economic activity.

Environmental, cultural and indigenous impacts carry greater weight with public opinion today than before, making the protests more politically sensitive for governments to tackle.

The mining industry is heavily affected by this trend. While the number of conflicts is not fully clear, the Latin American Observatory of Mining Conflicts has registered 284 conflicts across the region, impacting countries from Mexico to Peru, and they appear to be on the rise. The case of the Las Bambas mine in Peru is the most salient example of both the rising conflicts and government’s lack of desire to address them. National governments across the region, many elected on progressive environmental and indigenous platforms, are reluctant to take on the socially active electorate that catapulted them to power.

Mining Is Being Targeted

At the Las Bambas copper mine, one of the most important in the world, its Chinese owners had to halt operations as the road leading to it was blocked for 400 days by nearby indigenous communities. Three thousand workers were laid off, at a time of huge economic difficulty in the country.

Peru’s new government of Pedro Castillo was slow to act, leading the National Society of Mining, Oil and Energy to call the government reaction “erratic and biased,” confirming that “Las Bambas is being blackmailed by leaders who demand advantageous contracts.” Today the conflict endures with efforts for dialogue continuing. Chinese companies have also faced resistance in Ecuador.

But mining is not alone. In Colombia, incursions into private lands by indigenous activists have been ongoing for a few years. But the situation may be on the verge of growing with President Petro’s election, given his campaign promises to tackle land rights in Colombia. Just recently, sugar industry workers in the Valle del Cauca area near Cali complained of increasing land incursions into their fields by masked individuals causing damage to operations. In a tweet, President Petro did not condemn the land incursions and instead called for dialogue to lower tensions, but it reflects another flashpoint impacting private business.

In Chile, the largest indigenous minority, the Mapuche, have taken to occasional open insurrection in the south of the country. The country’s main north–south highway, for example, has been subject to indiscriminate attacks on cars and trucks driving along the road. On May 17, amid greater aggressiveness on the part of both the Mapuches and their adversaries, the government of center-left President Gabriel Boric announced a state of emergency in the region, despite having denounced such measures when they were used by rightist predecessor Sebastián Piñera.

The Desire to Squeeze Foreign Investors

What is driving the increasing social unrest targeting private business is more than the current global economic challenges. A powerful new cocktail of issues is accelerating a desire to squeeze companies — particularly foreign investors — that are supposedly reaping windfall profits from Latin American investments.

Environmental, cultural and indigenous impacts carry greater weight with public opinion today than before, making the protests more politically sensitive for governments to tackle.

Moreover, the expanding cadre of left-of-center governments in the region, such as President Gabriel Boric in Chile, President Pedro Castillo in Peru, and President Gustavo Petro in Colombia, have made environmental policy a big part of their political speech. Both Presidents Boric and Petro have committed to supporting the Escazú Agreement, which seeks to expand the “rights of access to environmental information, public participation in the environmental decision-making process and access to justice in environmental matters.” So far, 13 countries in the region have enacted the agreement.

Governments Are Staying on Sidelines

Government inaction in the face of these conflicts raises the political risk for foreign investors, especially in key strategic sectors such as mining that are driving many Latin American economies. A recent IMF study found that “On average, major [social] unrest events are followed by a 1 percentage point reduction in GDP six quarters after the event. Unrest motivated by socioeconomic factors is associated with sharper GDP contractions than unrest associated with political motives.”

Extractive industries — mining, oil and gas, forestry — are long-accustomed to working in inhospitable environments. But something new is happening in Latin America. Rather than defending investors who — for better or worse — account for important tranches of the national GDP and employment, national governments are opting to remain aloof to social unrest, which is closing plants and firing workers.

Latin America’s new leftist leaders are reluctant to be seen as working against the environmental and indigenous groups that helped them attain power. It’s no wonder that foreign investors are looking with caution at the region.