Not All Oil Is Equal. As Economies Recover, Which Oils Should Stay in the Ground?

Even after the worst of the global pandemic is over, business-as-usual will not resume overnight. And if a second wave of coronavirus strikes, global oil volumes could ebb even further.

Photo: Pexels

In May 2020, global greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations reached an all-time high. Even the worldwide pandemic that has depressed demand for gasoline, diesel and jet fuel cannot stop the Earth from dangerously warming.

One-off events like COVID-19 only temporarily reduce annual emissions. But atmospheric levels of climate-warming gases are cumulative; they will not decrease until more emissions are removed than go into the air year after year. Over the long-term, this will require the oil industry to undergo a wholesale clean energy transition, one that achieves large-scale change in capital allocation to carbon-free systems. But, in the short-term, each oil company needs to reduce the climate footprint of its own operations.

It could take as long as a decade for the economy to fully recover from the pandemic. Oil markets will remain in flux while global producers and refiners rebalance supply with demand. New oil market choices will need to be squared with climate risks. During this “great reset” companies must ask themselves: Which operations should we turn back on first? Which assets should remain off? And how do we convert our Paris pledges into durable climate actions?

Know Your Oil

Investors can pick and choose among different oil majors or independent producers and refiners — or the dedicated funds that track them. But they need detailed emissions data on current assets and future capital investments to measure a company’s real climate progress.

This knowledge exists. A new open-source tool called the Oil Climate Index (OCI) disaggregates the various lifecycle GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector in a fully transparent manner. For the industry’s part, producing, transporting and refining a barrel of crude oil (Scope 1 and 2 GHGs) vary widely, and account for up to 40% of total lifecycle emissions (including Scope 3 GHGs), depending on the oil selected and the production and refining processes used.

Given the massive volumes of oil and gas that circulate daily through the economy, the industry’s own GHG footprints are large enough to matter when calculating climate risks.

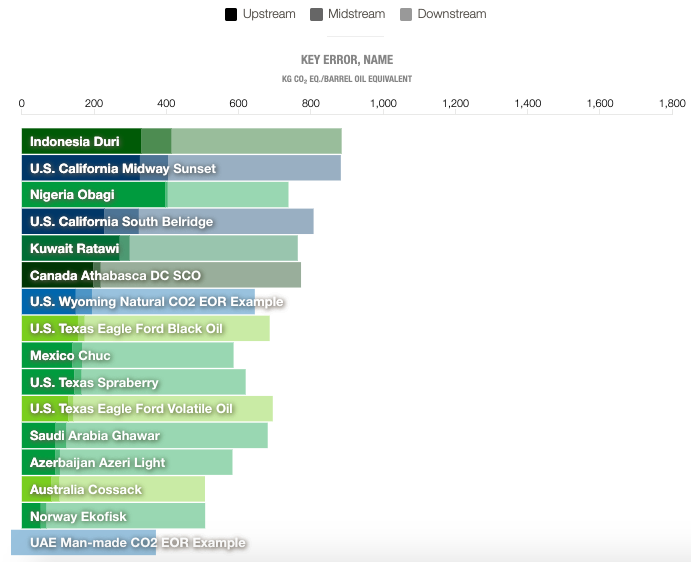

Estimated GHG Emissions for Select Global Oils (Ranked by Scope 1 and 2 Industry Emissions)

Source: Deborah Gordon, Adam Brandt, Joule Bergerson, and Jonathan Koomey, Oil Climate Index + Gas Preview. Upstream=production; Midstream=refining; Downstream=end uses

Assessments of upstream GHGs from nearly 9,000 oil fields in 90 countries and downstream emissions in nearly 400 refineries from 83 countries have been conducted using the OCI’s underlying models. Together, these studies find that the estimated carbon intensities of producing and refining a barrel of crude vary markedly, even when averaged by country.

Moreover, significant emission reduction potential exists, both upstream and downstream in the oil industry. Companies will need to employ these mitigation strategies to reduce GHGs in line with international climate targets.

Operating After Coronavirus

Even after the worst of the global pandemic is over, business-as-usual will not resume overnight. By year’s end, global oil and gas upstream spending is expected to shrink by $100 billion from 2019 levels, due to the 15 to 30 million barrels per day of petroleum demand cut out of the economy from March through June. If a second wave of coronavirus strikes, global oil volumes could ebb further. Global oil refineries could lose yet another 10 to 15 percent of their throughput, as they did in Q2 2020.

Refineries with the highest emissions should be the last to reopen. Other operators worldwide with higher-than-average refining GHGs — such as those in India, China, Venezuela, Iraq, the United States, and Brazil — need to demonstrably reduce their climate footprints in order to regain their social license to operate.

This also applies to oil producers: Those operators with higher-than-average production GHGs — such as in Algeria, Venezuela, Canada, Iran, Indonesia, Iraq, Nigeria, and the United States — must employ GHG mitigation measures before they turn up the volume.

Absent this information, markets will incorrectly assume that all oil production and refining pose the same climate risks. And, as soon as demand picks up, the globe will continue to warm where it left off pre-pandemic, elevating further spread of infectious diseases. This is a dangerous feedback loop that we do not want to set off.

Rebooting the Industry

Renewables certainly matter in combating climate change, but not everything can be electrified.

Much of what we currently consume — like medicines, paint, cosmetics and fertilizer — is petroleum-based and cannot be readily made from renewable energy sources. Until low-carbon substitutes are available for a majority of petroleum fuels and byproducts, oil companies are on the hook to shrink their production climate footprints and remake refining.

In recent months, numerous European oil majors have tightened their commitments to zero-GHG emissions. Eni is creating a new internal division, a Transition Company, to attract a different set of investors. Over the past decade, transition energy ventures have had higher and less volatile shareholder returns than oil companies. Equinor is planning to convert natural gas to hydrogen with carbon capture. BP plans to erase over 400 million metric ton of GHGs annually by investing in renewables and reducing methane emitted from its equipment. Shell is banking on a new power business and natural sinks like reforestation and carbon capture. Repsol plans to integrate renewables into its refining operations through the production of green hydrogen and the use of zero-carbon electricity.

Less progress has been posted by U.S. and most national oil companies whose clean energy transition plans lag behind European oil majors.

The oil and gas industry must dramatically reduce their climate impacts to align themselves with a 1.5 degrees Celsius climate target. This will require individual firms to transparently rank their resources and make operating and investment decisions based on open-source lifecycle GHG modeling. As long as oil and gas continue to flow, it will be incumbent on companies to rise to this challenge.