This Is Methane’s Moment: Battling Methane to Win the Climate War

A villager walks past a column of fire near Akaraolu, Nigeria — Nigerian gas flares release 35 million tons of carbon dioxide and 12 million tons of methane into the atmosphere each year. The IEA estimates that a 70% reduction in methane emissions from oil and gas systems is technically possible.

Photo: Chris Hondros/Getty Images

The International Energy Agency estimates that a 70% reduction in methane emissions from oil and gas systems is technically possible. Over the past 30 years, we have been fighting a war against greenhouse gases (GHG). And as climate change accelerates, casualties are mounting. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), an army of scientists agree that global warming is “widespread, rapid, and intensifying.” We are at “code red for humanity,” according to the United Nations.

For most of this war, the main enemy has been carbon dioxide, the principal GHG. But history has taught us that wars are won one battle at a time. Sometimes, a victory in a critical battle can build momentum that changes the entire trajectory of the war.

This is the case with methane.

Over the course of a single decade, leaks of this pollutant warm the planet 100 times more forcefully than carbon dioxide, and the IPPC references methane 682 times in its new report. This is methane’s moment, and battling this extremely potent climate pollutant now could make all the difference to abate the rapid warming that is flooding cities, igniting wildfires and baking global citizens.

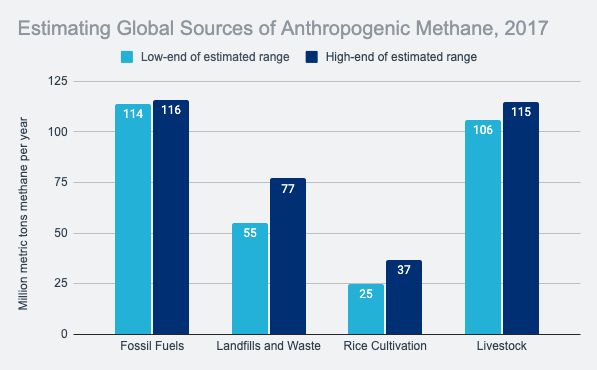

Methane’s sources are well known. Fossil fuels, mostly oil and gas systems and some coal beds (34%), livestock (33%), and landfills (22%) account for nearly all global methane emissions, which are estimated at 345 million metric tons per year. This estimate likely undercounts numerous sizable sources that are not reflected in current methane inventories.

Cost-Effective Methane Reduction

To fill the gaps, better attribution and accounting is emerging as new satellites, such as Carbon Mapper, are launched and integrated with other monitoring systems. Together, these instruments can be used to identify the three broad classes of methane emissions.

There are the massive but intermittent ultra-emitters, like oil and gas well blowouts that can pump well over 50 tons of methane per hour into the atmosphere. There are the large super-emitters, with emissions rates over 50 kilograms per hour, which leak from oil storage tanks, gas pipelines and compressor stations. And there are an array of smaller fugitive sources (less than 5 kilograms per hour) that are evident in commercial and residential equipment.

A 70% Reduction Is Possible

The International Energy Agency estimates that a 70% reduction in methane emissions from oil and gas systems is technically possible. And at least 10% of this reduction potential is cost-effective. In other words, companies and countries can profit from reducing one in every 10 tons of methane by selling rather than leaking gas.

Methane mitigation measures include: replacing existing devices such as pumps, seals, instrument air systems and motors; installing new control equipment, such as efficient flares and vapor recovery units; and conducting routine leak detection and repair operations.

It also matters where we mitigate leaks. Some countries are worse emissions offenders than others. Oil and gas producers in Russia and the United States are reported to have the highest methane emissions intensities, five times that of Saudi Arabia, Canada or Nigeria.

Taking Action

Voluntary action is in the works. For example, in North America, numerous companies are opting to self-certify their gas by grading assets based on their emissions intensity, best company practices, independent validation and real-time monitoring.

And in Western Europe, the world’s largest importer that buys 80% of its oil and gas from around the world, efforts are underway to adopt mandatory standards that reduce methane leakage. To help differentiate markets, investors are putting pressure on regulators to put rules in place to prevent excessive methane leakage.

Despite this, major investments in new gas infrastructure (including terminals that process and ship liquefied natural gas worldwide) are on the uptick. Current plans indicate that 3 quadrillion cubic feet of gas could be extracted through the remainder of this century. If 3% of this gas leaks, this would be the emissions equivalent of building 178 more coal-fired power plants worldwide — a disastrous move for our climate system.

Policymakers have at their disposal three main tools to arrest methane: information, regulations and pricing. Since we cannot manage what we do not know, the first step is greater emissions transparency and reporting. This involves routinely collecting open-source data and allocating public funds for monitoring systems that spot and freely report near-real-time emissions.

Given the limitations of voluntary corporate action, regulations can be adopted to standardize and enforce responsible operations as well as rapid leakage repair. And placing a price on methane can create valuable incentives that penalize bad industry actors and reward good ones.

Scientists have drawn clear battle lines. Methane simply cannot continue to leak into the atmosphere. Now, it is up to global policymakers to take up the charge and stop this dangerous super pollutant in its tracks. Our future depends on it.