Resurgence of ‘Bubble’ Culture in Japan: Nostalgia, or Confidence?

Pedestrians walk past an electronics stock indicator showing share prices on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in Tokyo. Tokyo stocks plunged early on March 23, as U.S. President Donald Trump unveiled tariffs on Chinese imports.

Photo: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images

The incredible price hike in the stock market in the past five years is provoking an interesting mindset among Japanese business leaders. This may be based on confidence in the Japanese economy looking forward, or perhaps just nostalgia for the “bubble economy” years of the mid-to-late 1980s.

Either way, businesses should not get carried away with the apparent promise of change, because the renewed fondness for the boom time of the 1980s may not necessarily result in improved economic activity, particularly an increase in wages or a burst of domestic consumption.

The Post-Bubble High

The Nikkei average hit JPY24,124 in January. This is still well short of the historical high hit in late December of 1989, when the index peaked at nearly JPY39,000, but the highest since late 1991 nevertheless, when the market started accepting the end of the 1980s bubble economy and coming to terms with it.

The cautionary tone has been disappearing gradually since the onset of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s second term in December 2012. The Nikkei index was as low as JPY9,738 then, and grew by 2.5 times by January 2018. Analysts are predicting the index will hit JPY27,000, or even JPY29,000 during 2018; and we are frequently hearing that this surge will continue. Already there is a growing sense of optimism, and the equity market is being treated as a proxy for wider economic performance.This is starting to reflect in renewed confidence.

Abenomics (those policies advocated by Abe) is often credited for this historical hike. Indeed, the administration has encouraged higher target return-on-equity in listed companies and endorsed the Government Pension Investment Fund’s participation in the equity market. This may or may not have raised confidence among international investors. Even if we put all the policy initiatives aside, the quantitative easing has invited the yen depreciation, a positive for the export-led economy.

However, some analysts point out that the post-Abe stock hike is not unique to the Tokyo Stock Exchange, claiming it is merely moving in parallel with the U.S. and European markets.

Farewell To Negative Post-bubble Sentiments

What is psychologically important for Japanese investors is that things may finally be brightening up post-bubble.

For corporate Japan, the post-bubble era has symbolized a loss of confidence. As the Nikkei average dipped below JPY10,000 several times post-bubble, the JPY38,000 figure in 1990 has come to be legendary. The soaring economy of neighboring China, the collapse of the “full-time employment” system and bankruptcies of major conglomerates have all had compound effects resulting in negative sentiment.

As a result, it is fair to say the bubble economy in Japan leading up to early 1992 was not just an economic phenomenon. In fact, especially for people older than the middle-age group today, it marks a sense of nostalgia for the “good old days.”

Moreover, because of the new trend of future growth expectations, those with direct experience of having lived in the 1980s bubble economy have become somewhat forgotten or considered less important. They are often called the “bubble generation.”

Resurgence of “Bubble” Subculture

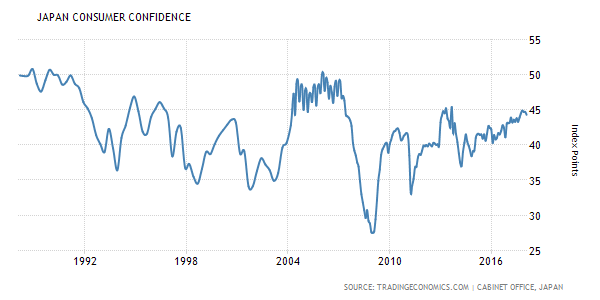

Consumer confidence in Japan hit a four-year high in November 2017 on the back of continuing economic expansion and low unemployment. At the same time, service sector business confidence also hit a 42-month high. These data clearly demonstrate that there is increasing optimism around the Japanese economy and business prospects going forward.

Exhibit: Consumer Confidence is Steadily Increasing

It isn’t only the official reading of the consumer confidence index that is looking promising. Anecdotally speaking, the signs of optimism can also be seen in popular media where odes to the bubble economy subculture are emerging in songs, movies and advertising.

“Dancing Hero,” a remake of an iconic 1985 disco hit, appeared on the Japanese pop charts in September. Though “Dancing Hero” is one of the signature songs that people associate with the bubble era, it’s been adopted by an entirely new generation.

This is but one example of a resurfacing of the bubble era mindset. Similar effects can be seen as other prominent cultural motifs, which can be viewed as symbolic of that era, back in vogue.

Can Consumption Catch Up with the Hype?

If this upbeat atmosphere can somehow result in greater consumption, it would be good news for the business sector and for the Abe administration. For now, however, this is not really happening.

While the Nikkei index has grown 2.5 times in the past five years under Abe’s leadership, consumer spending has only shown modest growth. In the fourth quarter of 2017, for instance, spending was JPY300 trillion, compared to JPY296 trillion five years ago.

Exhibit: Consumer Spending In Japan

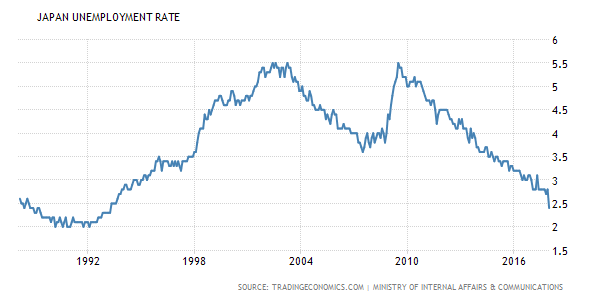

Underlying the weak spending is the modest rise in wages. Real wages fell 0.1 percent in September 2017 from a year before. This lags behind all other Asian nations, and this is despite an unemployment rate of under 3 percent, and the Nikkei index surge.

Exhibit: The Unemployment Rate Is Almost as Low as in The Bubble Era

The combination of strong stock prices, a low unemployment rate, weak wage growth and weak consumption paints a rather gloomy picture: The stocks may be performing at the expense of lower labor costs. It is no secret that, for decades, Japanese companies have been increasing the number of non-regular workers without reducing the workforce to save on insurance and benefit costs. Their share has reached record levels, and non-regular workers now make up more than a third of the nation’s employment.

Implications For Companies

Japanese companies have faced criticism domestically for hiring non-regular workers in large numbers, but the tightening labor market has started pressuring them to turn non-regular contract workers into permanent workers. It is still an open question whether the increase in the number of regular workers will lift up consumption, and, if so, when.

In what is a promising sign, Japanese businesses anticipate wage improvement in 2018. Given strong corporate performance and an improving economy in 2017, they can afford an increase in labor costs. Besides, there are also incentives in place for companies that increase pay. If wages do increase, this should create a virtuous circle in the economy, beginning with improved consumption. The onus, however, lies on businesses themselves.

For the government, on the other hand, weak consumption also works against the 2 percent annual inflation rate targeted by Abenomics. The government needs to see consumption pick up by 2019, as a consumption tax hike to 10 percent is planned for next year. After raising it from 5 percent to 8 percent in April 2014, the current administration has so far twice delayed this upcoming hike.

It remains to be seen whether the bubble momentum will finally translate into strong consumption throughout the next few months. With the Nikkei average plunging in January and February, the last thing the public, businesses and the government need is a burst like the one in the early 1990s. As of late March, the Nikkei average is reacting negatively to the Trump administration’s weak dollar policy and the plunging of the New York Stock Exchange due to fears of an impending trade war, showing its elasticity to the U.S. market.