The Growing ‘Publicness’ of Private Equity

A Japan Post Co sign is seen outside a post office in downtown Tokyo. In 2018, Japan Post created a co-investment fund manager called Japan Post Investment Corporation, which is co-investing in buyout deals from its initial $1.1 billion fund.

Photo: Christopher Jue/Getty Images

Institutional investors in Asia are increasing their allocations to private equity. Asian investors are looking for risk appetite, as they have studied the successes of private-equity programs of U.S. pension funds over the years. Greenwich Associates’ research shows that 42 percent of Asian institutional investors expect allocations to private equity to “significantly increase” in the next three years.

There are a few clear reasons for this—and some implications for the private-equity industry as a result.

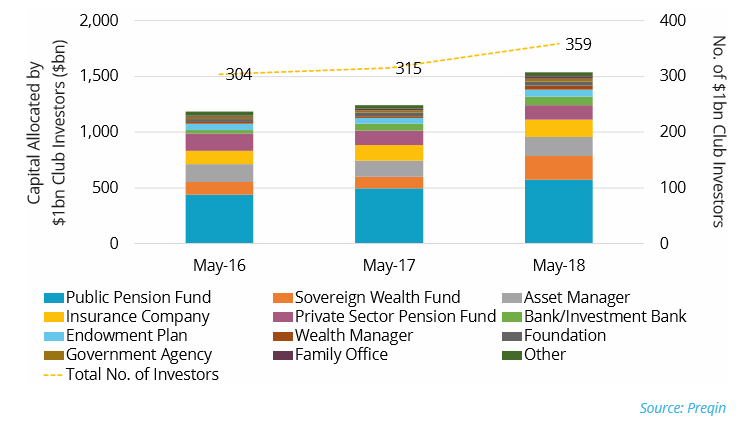

Among all private-equity investors, it is the mega-investors that are setting the trend for the asset class. This is most evident in Asia, which is home to no fewer than five of the 10 largest institutional investors in private equity globally: Kuwait Investment Authority, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, GIC, China Investment Corporation, and National Pension Service (South Korea).

Exhibit 1: Largest Institutional Investors by Current Allocation to Private Equity (as of May, 2018)

The latest such investors to join the fray are from Japan. The Japan Post Bank, one of the biggest banks in the world with $1.87 trillion in assets, plans to invest up to $78 billion in alternative investments in the next three years. Similarly, Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), the largest pool of retirement savings in the world, is also slowly but steadily entering the private-equity space.

Japan Post Bank and GPIF have historically been very passive investors, focusing on government bonds, and in that context, their recent decisions on private equity reflect a sea change in investment philosophy and an increasing appetite for private equity that is also being witnessed across the rest of Asia.

Increasing Appetite among Large Investors

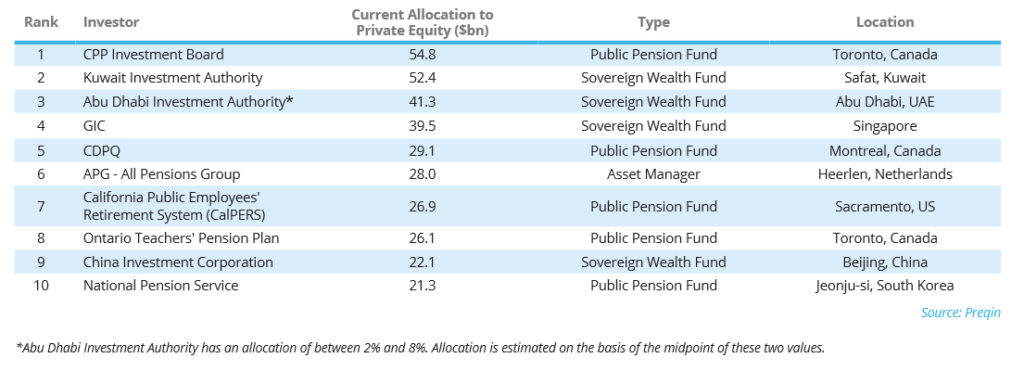

Asian investors are not alone in increasing exposure to private equity. Globally, large investors such as public pension funds and sovereign wealth funds are increasing allocations to private equity. According to Preqin, for example, the number of investors with more than a billion dollars of exposure to private equity is 359, up 14 percent from 315 in 2017. This “$1 billion club” consists of investors such as public pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, asset managers and insurance companies.

Exhibit 2: Capital Allocation of $1 Billion Club Investors by Investor Type, 2016 – 2018 (as of May, 2018)

There are multiple reasons for this phenomenon. One part of the story is about investors themselves. In developed economies, pension funds are growing in size as their populations are aging. The payment pressure is increasing as collections are growing difficult, as in the case of the GPIF. Meanwhile, in successful developing economies, there is simply more capital to invest. In both cases, institutional investors are faced with a strong need for higher returns.

The other part of the story is about happenings in the private-equity asset class. First, the sheer size of private-equity funds is providing abundant capacity for mega-investors. Private-equity funds raised a record $453 billion in 2017, making $1 trillion of capital available for managers to invest in the year. Second, returns from private-equity investing have outstripped returns from other asset classes. According to an analysis of 163 U.S. public pensions, the median annualized return for the past 10 years from private equity was 8.6 percent a year, outperforming public equity (6.1 percent per year), fixed income (5.3 percent per year) and real estate (4.7 percent per year).

The strong appetite for private equity among institutional investors has, in some cases, evolved into investing directly into companies by co-investing with private-equity managers they are invested with. For example, in the first quarter of 2018, Singapore-based sovereign wealth fund GIC invested in a greater number of deals in Asia than any other investors in private equity. The incentives to co-invest range from increasing exposure to attractive investment opportunities, to squeezing fees paid to private-equity funds.

A similar trend is playing out elsewhere. In Japan, for example, in 2018, Japan Post created a co-investment fund manager called Japan Post Investment Corporation, which is co-investing in buyout deals from its initial $1.1 billion fund.

The ‘Publicness’ of Investors and Implications

These leading private-equity investors are all huge, but seen from a different perspective, they are all invested in by the public. Public pension funds manage public pensioners’ money; sovereign funds manage treasury funds and taxpayers’ money; asset managers manage miscellaneous investors’ capital; and insurance companies invest from people’s investment into all kinds of insurance products that are tied to our everyday lives.

In other words, the ultimate end-investors of these mega-investors are regular individuals. This overwhelming “publicness” of investors is having consequences on the private-equity industry.

First, private equity in general is increasingly under greater scrutiny by the public, including through media and social media platforms. The public’s interest isn’t only in the performance, but also on the fees paid to managers and the investment behavior of funds. The days of private-equity investment being a covert closed-door operation are coming to an end.

For a long time now, CalPERS has posted fund-by-fund performance figures for its investment online, and many pension funds now do the same. Similarly, pressure on fees paid to private-equity managers is already increasing. While management fees have always been an issue, it has been so only in the investor community. The publicness of the asset class is now taking the concern to a new level.

Separately, the investment behaviors of private-equity managers are being increasingly monitored. More public investors need to make sure that their underlying private-equity managers are meeting environmental, social and governance objectives. While there may still be investment funds around the world that invest in controversial companies or industries; private equity has been forced to grow into a more civil and legitimate asset class, with investors seeking more responsibility from their fund managers.

This behavioral issue cuts both ways, as the publicness of the industry raises the bar for investors as well. Any wrongdoing on the part of the investor can also result in penalties under the public spotlight, because public money is at stake. This was evident in the highly publicized bribery case in CalPERS, where the ex-CEO ended up pleading guilty to fraud and bribery charges in 2014.

The Next Stage

Going forward, as large institutional investors become more prominent players in the private-equity landscape, we can expect to see a continuation of these trends. And in more ways than one, Asian investors could be the ones driving the change.

The implications of these trends on the private-equity industry will play out over time. But one thing is certain—private equity will need to engage with the publicness of the large institutional investors.