The Terrorism Risk Insurance Act Expires Next Year. An Expert Explains Why Congress Must Renew It.

An interview with

An armed NYPD officer guards the New York Stock Exchange in New York City. Last week, the U.S. Congress held hearings on reauthorizing the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program.

Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Last week, the U.S. Congress held hearings on reauthorizing the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, which was established in 2002 via the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act, known as TRIA. TRIA was passed after 9/11, when private insurance companies and re-insurers started to show reluctance to provide coverage against acts of terrorism. The act guarantees that the U.S. government will cover a significant share of the loss in the event of a terrorist attack, over a certain dollar amount. The Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2015 extended the program through December 31, 2020.

BRINK News spoke with Howard Kunreuther, co-director of the Wharton Risk Center and Decision Processes Center, who testified before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs on June 18 in a hearing on the reauthorization of TRIA. We asked him about the value of TRIA and its successor bills and the responsibilities of both the public and private sectors in terrorism risk financing.

BRINK News: Would you say that the act has been a success?

Howard Kunreuther: Yes, I would say so. This program has led insurers to offer terrorism coverage to commercial firms. And according to a recent report by Marsh, about 60% of U.S. companies have bought insurance against terrorism that became available as a result of TRIA.

BRINK: What would that percentage have been without the act in place?

Mr. Kunreuther: Before 9/11, terrorism was covered in all commercial property insurance policies. Insurers did not explicitly name terrorism or rule it out as a covered event, because before 9/11 they considered the likelihood of a terrorist attack that would cause significant damage to be extremely low. Afterward, terrorism was offered by only a few insurers at extremely high prices, but most insurers did not want to offer coverage, and that’s the reason that TRIA got passed.

BRINK: And what kind of sectors of the economy or businesses have taken this up?

Mr. Kunreuther: According to Marsh, education companies purchased property terrorism insurance at a high rate (87%), followed by media (81%), financial institutions (79%), real estate (75%), hospitality and gaming (72%), and health care organizations (70%). The three industry sectors with the lowest take-up rates were manufacturing (49%), chemicals (46%), and energy and mining (22%). These differences seem to be partly due to some industries having exposure concentrations in central business districts and major metropolitan areas that are likely perceived as being at higher risk of a terrorist attack.

BRINK: Has TRIA ever been activated?

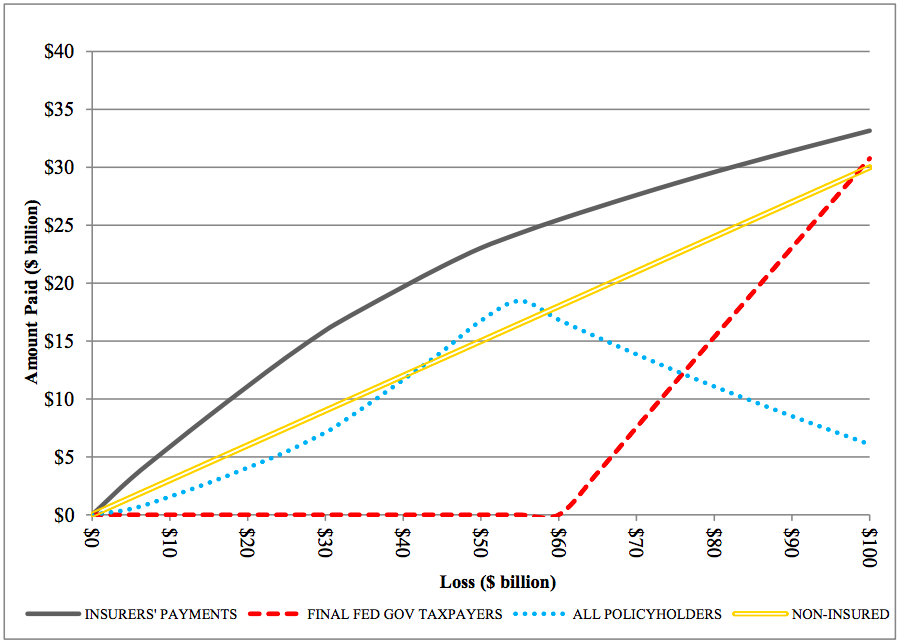

Mr. Kunreuther: No, because we have not had a major terrorist attack since 9/11. The act has a complicated formula; we have done studies at the Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center that indicate that until the losses exceed $60 billion, private insurers will cover them all. The federal government will be a backstop if the losses exceed $60 billion and will then recoup their payments to the insurers.

In my testimony to Congress, I’ve showed a graph indicating this.

Figure 1: Analysis of Possible Amount Paid by Stakeholders for Different Loss Amounts from Terrorist Attacks in New York City under the 2015 TRIA Legislation

BRINK: The act is designed to cover damage to property and infrastructure and loss of life. What happens in the event of, say, a cyberattack?

Mr. Kunreuther: Cyber is a tricky issue, and there are some questions with respect to what would happen if a terrorist attack was perpetrated as a cyberattack.

Some firms have provided special coverage against cyber losses from a terrorist attack, but it is difficult to price the risk given the uncertainties around the likelihood of such an attack and its consequences. For this reason, in my testimony, I propose that in analyzing the renewal of TRIA, Congress should consider having the federal government cover cyber losses from a terrorist attack and then recoup their claims payments from the private insurers.

BRINK: The act is coming up for renewal. What are your recommendations as to how it could be improved?

Mr. Kunreuther: During my testimony before Congress, I emphasized the need for a public-private partnership that recognizes the cognitive biases that characterize our intuitive decision-making with respect to low-probability events. I focused on five of these decision biases, which underpin why people and firms under-prepare for disasters. The biases and possible solutions to overcome them are detailed in the book that I wrote with Robert Meyer, my co-director of the Wharton Risk Center: The Ostrich Paradox: Why We Underprepare for Disasters.

It is very hard to change these biases, so we propose accepting them and then developing strategies for dealing with them that improve individual and organizational decision-making. To some extent, they play a role with respect to what will happen in the future with respect to reducing future losses from terrorism.

BRINK: Could you give us an example?

Mr. Kunreuther: I’ll give you an example of one of the most common and critical biases, which affects all of us: myopia. It causes us to focus on very short-term planning horizons when determining whether to invest in measures that could reduce future damage from terrorist attacks. As a result, we often don’t appreciate protective investments.

Investing in protective mechanisms often requires high upfront costs. If you only consider the potential benefits from these measures for the next several years, then you may not want to adopt the measure because the investment doesn’t pay off during this short interval. If one had estimated the potential benefits over a five or 10 year period, it is likely that the decision-maker would find many of these measures to be financially attractive.

I propose that TRIA include government-provided economic incentives for property owners to invest in mitigation measures that could reduce terrorism losses and that they or financial institutions offer long-term loans to spread the cost of risk-reduction measures for reducing these terrorism-related losses. Insurers that offer terrorism coverage can then reduce their premiums because the claims would be lower. This creates a win-win situation for all stakeholders: Firms would find that the cost of the loan (if the measure is cost effective) is less than the insurance premium reduction. Insurers will have lower claim payments, and the general taxpayer will be responsible for fewer damage payments.

BRINK: What about mitigation measures?

Mr. Kunreuther: I also pointed out in my testimony that the United Kingdom, where Pool Re is their terrorism insurance organization, is spending a good deal of time on trying to encourage firms to adopt mitigation measures by working closely with the UK government. The United States might want to consider looking at what the UK is doing in that regard.

Today, mitigation is not a part of TRIA, and my feeling is that it should be. We need more research and studies in the U.S. as to what measures are likely to be cost-effective in reducing the likelihood of future terrorist attacks and the resulting damage.