Which Way Is Inflation Heading?

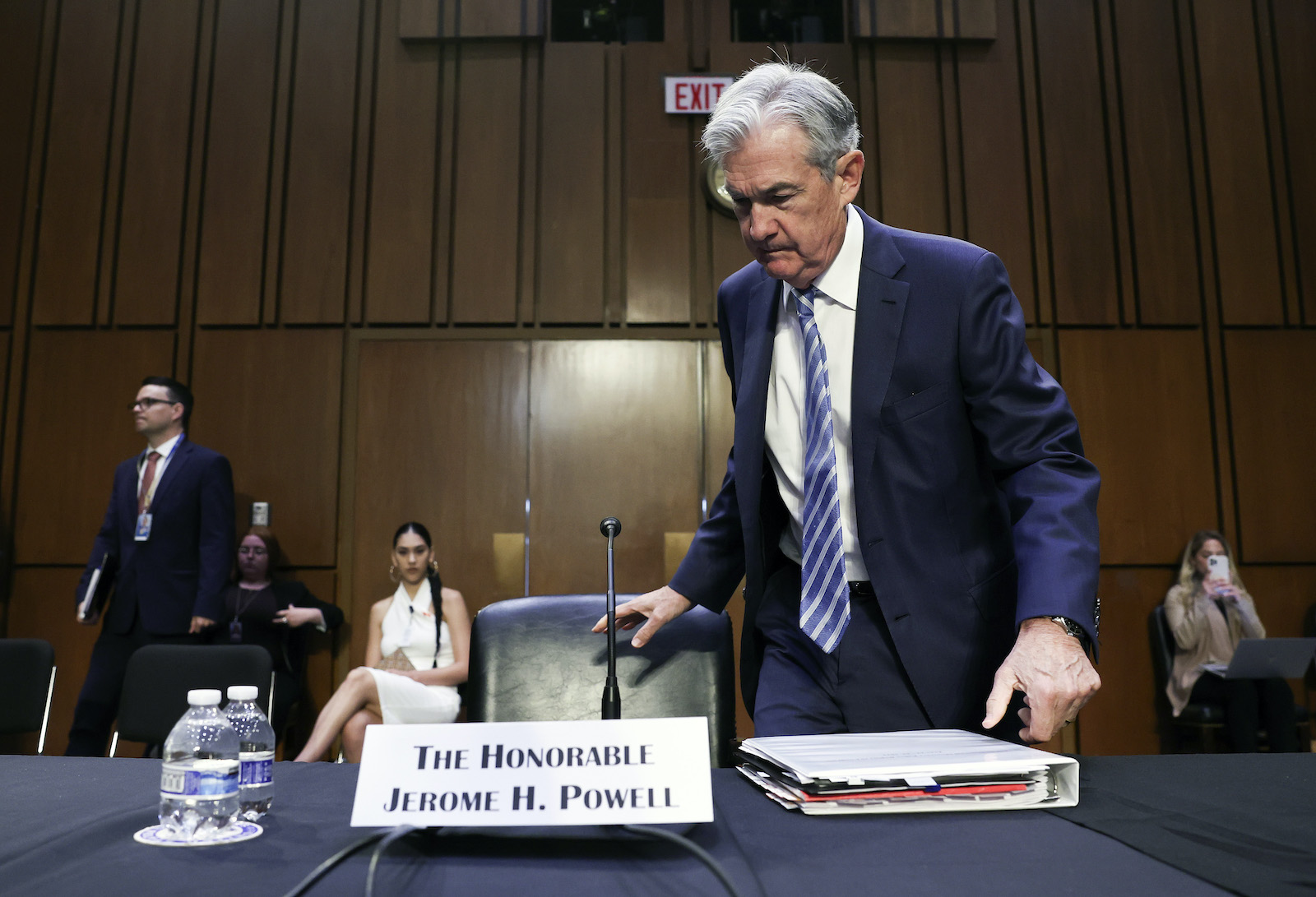

Jerome Powell, Chairman, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, arrives to testify before the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee on June 22, 2022 in Washington, DC. Powell testified on the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to Congress during the hearing.

Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images

The latest economic data shows inflation in the U.S. running at 8.5% in July. This is a drop from 9.1% in June. July’s retail sales figures were flat, which some analysts interpreted as a hopeful sign. After stripping out food and fuel costs, prices climbed by 5.9% through July, matching the previous reading, according to The New York times.

Another sign that inflation may be decelerating in the U.S.: Gas prices have fallen by $1 a gallon, back to the same levels as March, after peaking in June.

However, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has signaled a willingness to inflict “some pain” on households and businesses in order to maintain the pressure on inflation. His speech led to the Dow dropping by 1,000 points, and market analysts believe that the Fed could raise interest rates by as much as 0.75% when it next meets later this month.

In the U.K., inflation hit 10.1% in July, and the Bank of England is predicting that it could reach in excess of 13% in the final three months of this year and remain “very elevated” for much of 2023. Goldman Sachs says it could rise as high as 20% in the winter if energy prices continue to climb. However, the Bank of England expects inflation “to slow down next year and be close to 2% in around two years.”

The Primary Drivers of Inflation

According to the Bank of England, there are three primary reasons for inflation in the U.K. The biggest is higher energy prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has led to a doubling of the price of natural gas since May.

A second reason is COVID, which is still causing disruptions in the supply chain and an increase in demand for consumer goods at the same time, causing prices to rise. The third is that, in the U.K., there are more job vacancies than there are people to fill them, as fewer people are seeking work following the pandemic. “That means that employers are having to offer higher wages to attract job applicants. And prices for many services have gone up.”

Higher wages in the U.K. also appear to be creating an inflationary spiral, with a shortage of workers causing a rise of wages, which is driving up prices, which in turn fuels more wage rise demands. In the rest of Europe, there has been more wage restraint so far with most sectors in Germany, for example, agreeing to limit wage increases to a range between 3 and 4.5%.

China Is Cutting Its Interest Rates

In most parts of the world, inflation appears to still be climbing. In the eurozone, inflation hit a new high in August at 9.1%. Germany’s central bank chief is predicting prices could hit 10% by the end of the year, primarily because of the cutoff in Russian gas. Prices in Australia rose by 6.1% last month, in South Africa by 7%, 14% in Russia, and in Brazil by 10%, although this is the lowest it’s been since December.

Turkey’s inflation rate is one of the highest, at around 80%. Even so, the Turkish president is calling for a cut in interest rates, claiming that it is interest rate hikes that cause inflation, the opposite of conventional economic thinking.

In China, the Central Bank has been cutting its interest rates, suggesting that it is more concerned about slowing economic growth than inflation. The Chinese economy is being hit by extended COVID lockdowns and significant problems in the country’s real estate market. Some analysts are even predicting an annual growth rate of less than 3% in the country, which would be the lowest level in two decades.

Risk of Stagflation

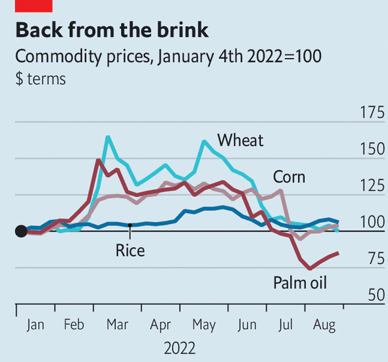

One hopeful piece in the puzzle has been a recent drop in food prices. Wheat, corn and palm oil are all back to their price levels of six months ago, before the Ukraine conflict. The main driver of this, ironically, appears to be a bumper wheat crop in Russia which has increased the amount of Russian grain exports. However, many developing countries will still suffer high food prices because of the decline of their currencies against the strong dollar.

There is concern that the global economy could become stuck in a stagflationary loop of long-term elevated inflation and low economic growth.

The IMF has lowered its economic growth predictions in the U.S. to 2.3% this year and 1% next year. In China, the IMF estimate is down to 3.3% this year — the slowest in more than four decades, excluding the pandemic — and in the euro area, the growth rate is revised down to 2.6% this year and 1.2% in 2023, reflecting spillovers from the war in Ukraine and tighter monetary policy. The European Central Bank is due to announce its next rate rise this week.