Supporting International Employees Through an Emergency

Ukrainian refugees flee the Russian military by crossing the border into Poland. Companies need tailored support and risk mitigation measures to support their employees affected by the conflict in Ukraine.

The tragedy in Ukraine reminds us that managing an international workforce is a huge responsibility and a difficult task to manage. While managers and international HR teams do not face crises alone and are supported by other specialist teams, they are still dealing with dramatic events and their consequences for international employees.

Perhaps we have been using the concept of employee well-being or employee experience too lightly in the past. The pandemic has already prompted many companies to go beyond pure rhetoric and develop comprehensive programs to protect the physical, mental, social and financial well-being of their employees.

Tailored support and risk mitigation measures are unfortunately required again as companies are forced to act decisively to support their employees affected by the conflict in Ukraine. Companies are also reassessing their position in countries affected by sanctions, like Russia or Belarus, as well as monitoring the situation in neighboring countries impacted by the war.

Here are some important things to bear in mind when dealing with emergencies.

Providing Enough of the Right Kind of Support

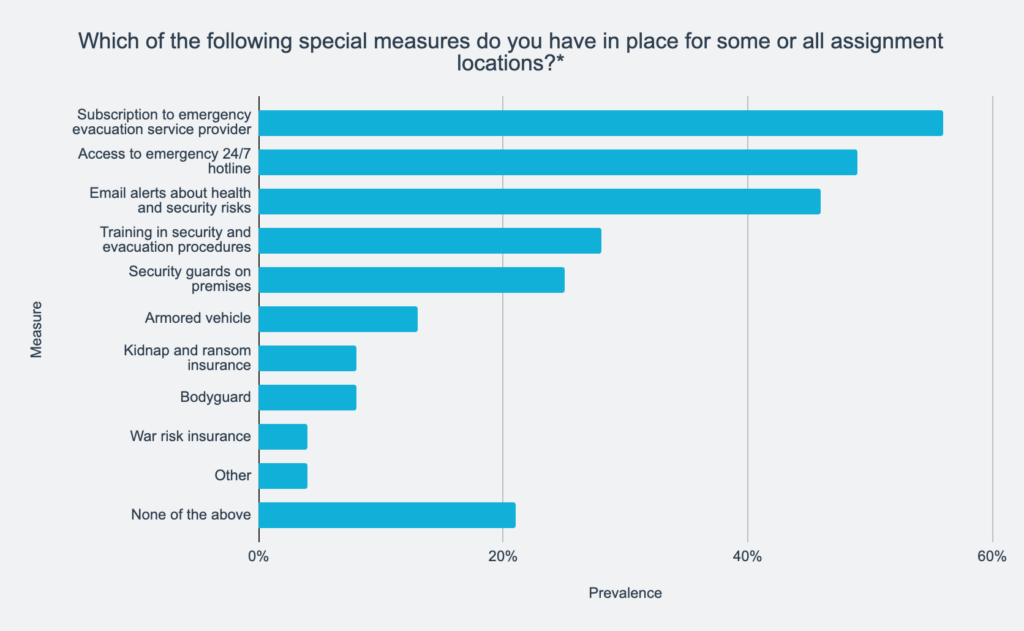

The first step is to make sure that the basics are in place and that the company can rely on a robust network of providers to deal with difficult and emergency situations.

Source: Mercer’s 2020 Worldwide International Assignment Policies and Practices Survey.

*More than one answer possible.

However, insurers and security providers cannot fully replace companies’ in-house teams and their knowledge about employees. Dealing with human implications and long-term consequences of emergencies remains the responsibility of HR teams.

Companies occasionally ask if they have to consider issues that are covered by insurance in hardship assessments. But insurance does not fully eliminate the hardship — in case of an emergency, expatriates still face risks until they are evacuated or can access treatment in a hospital meeting international standards. Insurance does not replace a good process managed by the company and does not exonerate companies from paying a hardship allowance. The same logic goes for security, housing, schooling and practical support.

Employees Have Varied Needs

In an emergency situation, the initial focus of a company’s response should be ensuring the safety of employees directly at risk. However, many other employees may be impacted, including, for example, colleagues with family members affected by the war. They may require different forms of assistance ranging from practical issues such as work flexibility to mental health and financial support. Other employees might feel anxiety, frustration and the need to do something meaningful — they expect some guidance and suggestions from their organizations.

HR teams might not be aware of these issues, so it is important to reach out to all employees, open the channels of communication, and find out what their specific needs are.

Who and When to Evacuate?

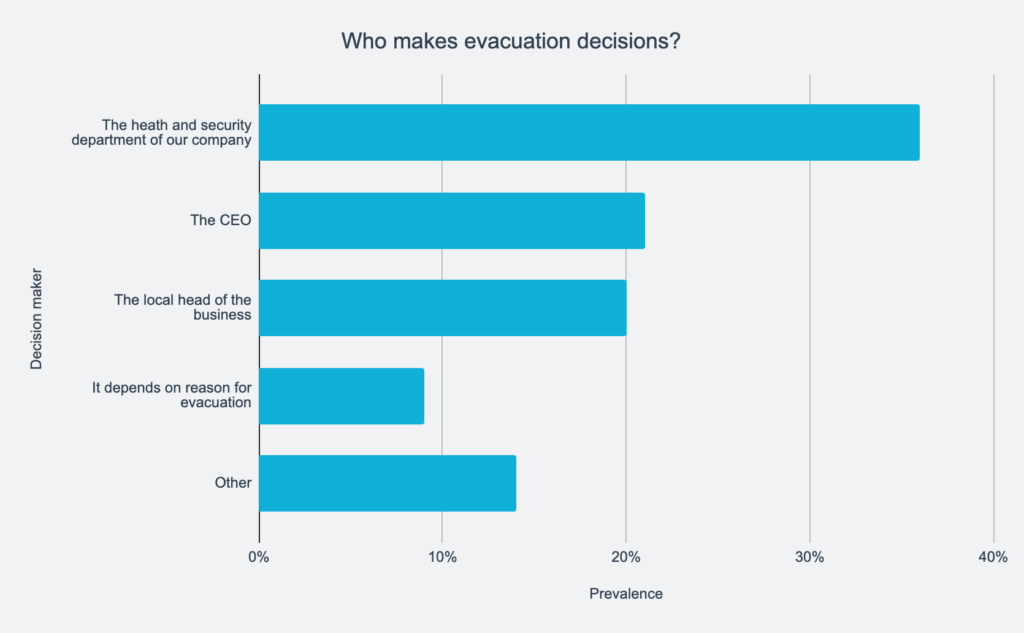

Government sites provide recommendations for evacuations, but their guidance is insufficient. Different countries may provide different recommendations for their citizens at different points in time. Companies with diverse expatriate workforces need a more structured approach and a clearer message. Whether to evacuate requires consideration regarding who should make the decision to evacuate, who should be evacuated and when — especially in situations like the conflict in Ukraine. But it is not necessarily safe to assume that the company will evacuate everybody in case of problems.

Source: Mercer’s 2020 Worldwide International Assignment Policies and Practices Survey

Should you only evacuate expatriates — or all employees? Is it morally acceptable to differentiate? What are the practical implications if everybody has to be evacuated?

Consider locally hired foreigners who do not benefit from a guarantee of repatriation and who were not relocated by the company in the first place. The company may find itself relocating employees to a third country that is not their home location or repatriating them to a home country that they left long ago and where they don’t have accommodation, a local support network or family left.

Companies have to determine if they are going to evacuate their employees, only the family of the employees or ask their employees to stay as the situation could be under control. The challenge is to understand the implications of these decisions and what message they send to both expatriates and local employees.

The situation in neighboring countries should also be monitored. The question of evacuation may also apply to countries beyond immediate conflict zones, for example, countries under sanctions like Russia and Belarus.

Giving the option to evacuate or not is leading to another issue — duty of care.

The Concept of Duty of Care

Should employees be allowed to decide whether or not they want to stay in an area where others are evacuating? The risk is that flexibility and freedom of choice could lead employees to put themselves in harm’s way or delay the decision to leave until it is too late.

The concept of duty of care is not limited to a legal obligation to protect employees — it extends into reputation and moral issues. In the strict sense, duty of care is about taking all possible steps to ensure the safety, health and well-being of employees. This is a legal requirement that companies cannot ignore. The scope of duty of care is wider than many think, and it applies to the family of an employee if the family is relocated to the host location with the employee and sometimes when the family does not live abroad and just visits for a short period of time.

Experienced expatriates might be tempted to decide for themselves. But too much flexibility is a risk that cannot be mitigated by putting disclaimers in employees’ contracts. Duty of care is a matter of trust and credibility for the company, and it could affect recruiting and retention. If a problem arises, the impact to the company’s reputation could be significant.

Getting Out of the Country Is Only the First Step

The evacuation will trigger a host of consequences that companies and HR will have to deal with, such as:

- How to deal with temporary accommodation in the home country or in a third country

- Managing employees’ physical and mental well-being after a traumatic experience

- Providing schooling for the expatriate children

- Ensuring continuity of work for relocated employee (remote working or re-assignment to new tasks)

- Revising pay and benefits arrangements

Repatriating a couple of employees is not a problem, but when dealing with a large number of employees, these tasks take a completely different dimension and test the resources of HR teams.

Additional Burden Upon Repatriation: Compliance, Tax, and Immigration

HR might also have to deal with new compliance issues.

There are implications of unexpected repatriation or relocation in terms of tax, immigration and compliance — starting with basic ones, like securing visas and registering employees relocated at short notice.

Some of these considerations might seem mundane compared to the risks that employees have been facing, but as time goes on, HR teams and employees will be swamped with paperwork, costing companies and employees time and money.

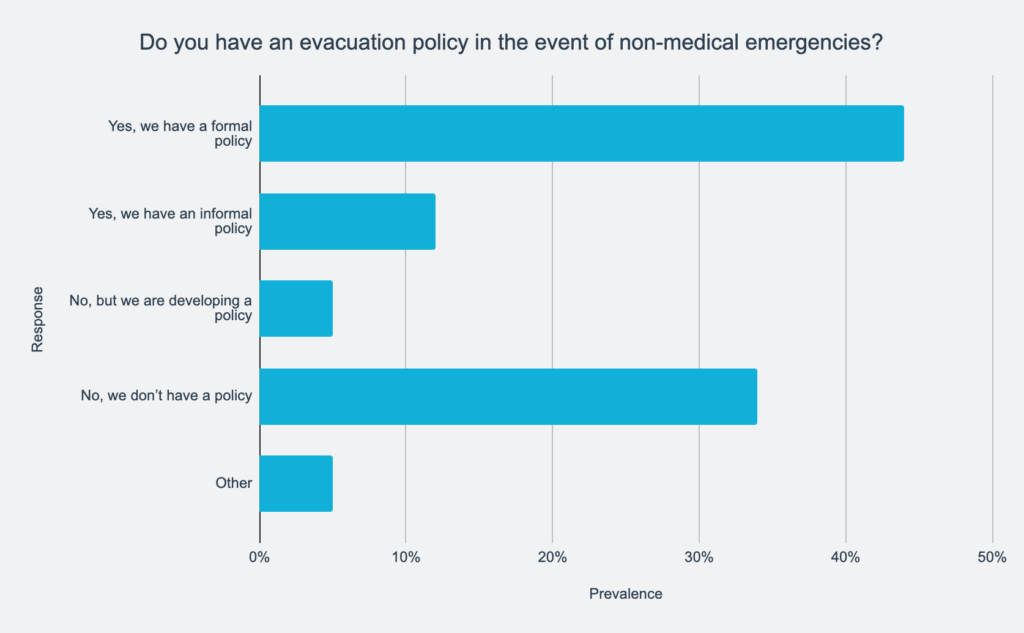

Not All Companies Are Equal When Dealing With Emergencies

Large multinationals operating routinely in hardship locations have robust support networks and processes to deal with emergencies. But this may not be the case for other companies with fewer resources, smaller operations on the ground or more limited experience in hardship destinations. In fact, almost 39% of organizations report that they do not have an evacuation policy in place or are still trying to develop one.

Source: Mercer’s 2020 Worldwide International Assignment Policies and Practices Survey

HR teams can reach out to companies operating in the same area to cultivate mutually beneficial support systems. This could involve pooling resources and developing a network to provide a detailed evacuation strategy and ongoing support for assignees and their families.

Making a Meaningful Contribution

The image of companies and its “employer brand” are tested in times of crisis. Employees will remember what was done and if their employer was true to its values and promises.

In several years, HR professionals might not remember what policy details or benefit issues they had been discussing in quieter times. But they will remember vividly what they did to help assignees escape from a dangerous situation and what support they extended to local colleagues and their families. Managers and international HR professionals who have dealt with emergencies have found it stressful but also view it as one of the most rewarding tasks of their career.