What Are the Targets in the U.S.–China Trade War?

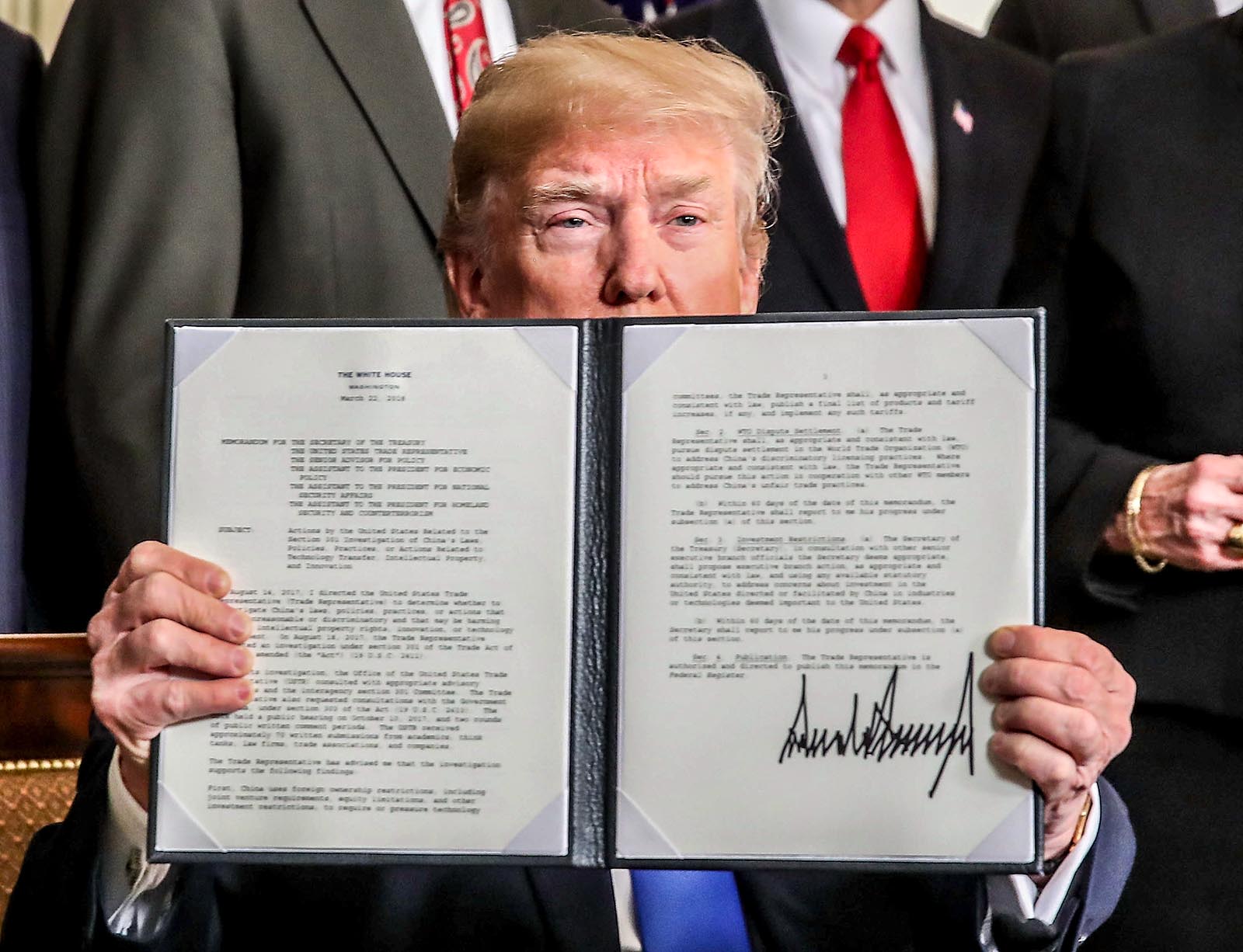

President Donald Trump holds up his signed memorandum on sanctions against China in the Roosevelt Room at the White House, March 22, 2018.

Photo: Mark Wilson/Getty Images

The U.S.–China trade war is escalating faster than expected, but the real question is: What are the ultimate targets for the two countries? To answer this question, we analyzed the 1,333 products covered by the U.S.’s latest action against China’s breach of intellectual property rights and classified them based on two criteria: the technological content and the weight in China’s total exports to the U.S. We then applied the same methodology to China’s second round of export tariffs announced this week and compared the two.

We found that the U.S. tariff package appears to be much smaller than the estimate produced by the U.S. administration of $60 billion, based on our bottom-up estimation of the export value of the 1,333 products (Chart 1). However, 84 percent of the total value of the products are high-end exports, while the low-end ones only constitute 3 percent of total value (see Chart 2).

As for China’s list of targeted imports from the U.S. (106 in total), our estimated value is almost the same as the one announced by the Chinese government ($50 billion). However, 50 percent of the products on China’s list are at the lower end of the value chain.

Automotive Industry the Most Affected

Our estimation of value of imported products covered by the tariffs of $29 billion is equivalent to 25 percent of U.S. imports from China.

Among all products, there are three key targets. Automobile is the most affected sector, and equal to 7.7 percent of U.S. exports into China. Advance instruments (optical, measuring and medical instruments) and nuclear reactors, machinery and mechanical appliances constitute 6.4 percent and 6.0 percent, respectively.

High-tech categories tend to have a higher proportion of products subjected to import tariffs, varying from 44 percent to as high as 90 percent. For the most extreme case, 90 percent of optical, measuring and medical instruments will be affected. Eighty-one percent of vehicles and 70 percent railways exports will also be subjected to additional tariffs, which are the sectors that China is trying to grow both in global market share and technological advancement.

The list also includes sectors in which China is still struggling on the technological ladder, in particular arms and aircrafts. We have discussed in our previous report that China’s “Manufacturing 2025” program is a key focus. The goal is not trade balance but technological advancement.

For China, It Is About Scale

China’s retaliation so far appears to be aimed at hurting U.S. exports in terms of scale, and this includes large items such as soybeans, aircraft and vehicles that amount to 29 percent of U.S. exports into China. The main targeted agricultural products (including soybeans and cereals) account for 11.6 percent of China’s imports from the U.S., followed by 9.4 percent in aircrafts and 8.9 percent in vehicles.

More than 50 percent of mineral fuels and plastics articles, which are also of some importance in imports, are also subjected to tariffs. Semiconductors, the fourth largest item in China’s imports from the U.S., have been exempted probably due to the irreplaceable nature and the urgent need of such technologies. In contrast to the U.S., China’s list covers more primary products than high-tech products, and therefore the impact will be more direct but short-lived.

Chinese Tariffs Will Impact China Too

The fact that China has high reliance on the above products also means tariffs could hurt Chinese producers and consumers. Beyond semiconductors, automobile makers, which export about 30 percent of their products into China, will be subjected to another 25 percent tariff on top of the existing 25 percent. However, at the same time, 28 percent of China’s imported vehicles originate in the U.S. Interestingly, Premier Li Keqiang promised to cut the tariff on automobiles during the People’s Congress, suggesting that a tariff on vehicles is clearly not desirable for China.

The same can be said for soybeans and aircrafts, as China buys 41 percent of imported soybeans and 63 percent of imported aircraft from the U.S. The recent fall in pork prices could offer room for China to retaliate through soybeans, a key source of piglet feed, and China could also switch to non-U.S. companies to meet the demand in aircraft, but whether this is sustainable is another question.

Due to the large scale of purchases by China, it may not be that easy to substitute with new sources based on constraints in infrastructure and productivity in the short run. Higher inflation and the lack of competition on mechanizing could also mean higher costs for China.

Stopping China from Gaining a Technology Advantage

Our interpretation of these findings is that the U.S. is not really targeting the bilateral trade deficit with China, but trying to constrain China from climbing higher up the technological ladder.

The U.S. is hitting China where it hurts the most, especially as technological modernization is officially enshrined in China’s Manufacturing 2025 plan, hence the strong retaliation by China. However, it seems clear that China is trying to minimize the self-inflicted cost of retaliation by focusing, to the extent possible, on lower-end products.

In other words, both the U.S. and China are targeting each other’s weakest points—the U.S. is targeting China’s future technological capacity, and China is responding by targeting U.S. exporters’ present revenues. The instantaneous impact on U.S. exporters could well explain President Donald Trump’s immediate response with an even larger package of import tariffs. In such circumstances, it is hard to think of a way to negotiate.