China Is Moving Rapidly Up the Rare Earth Value Chain

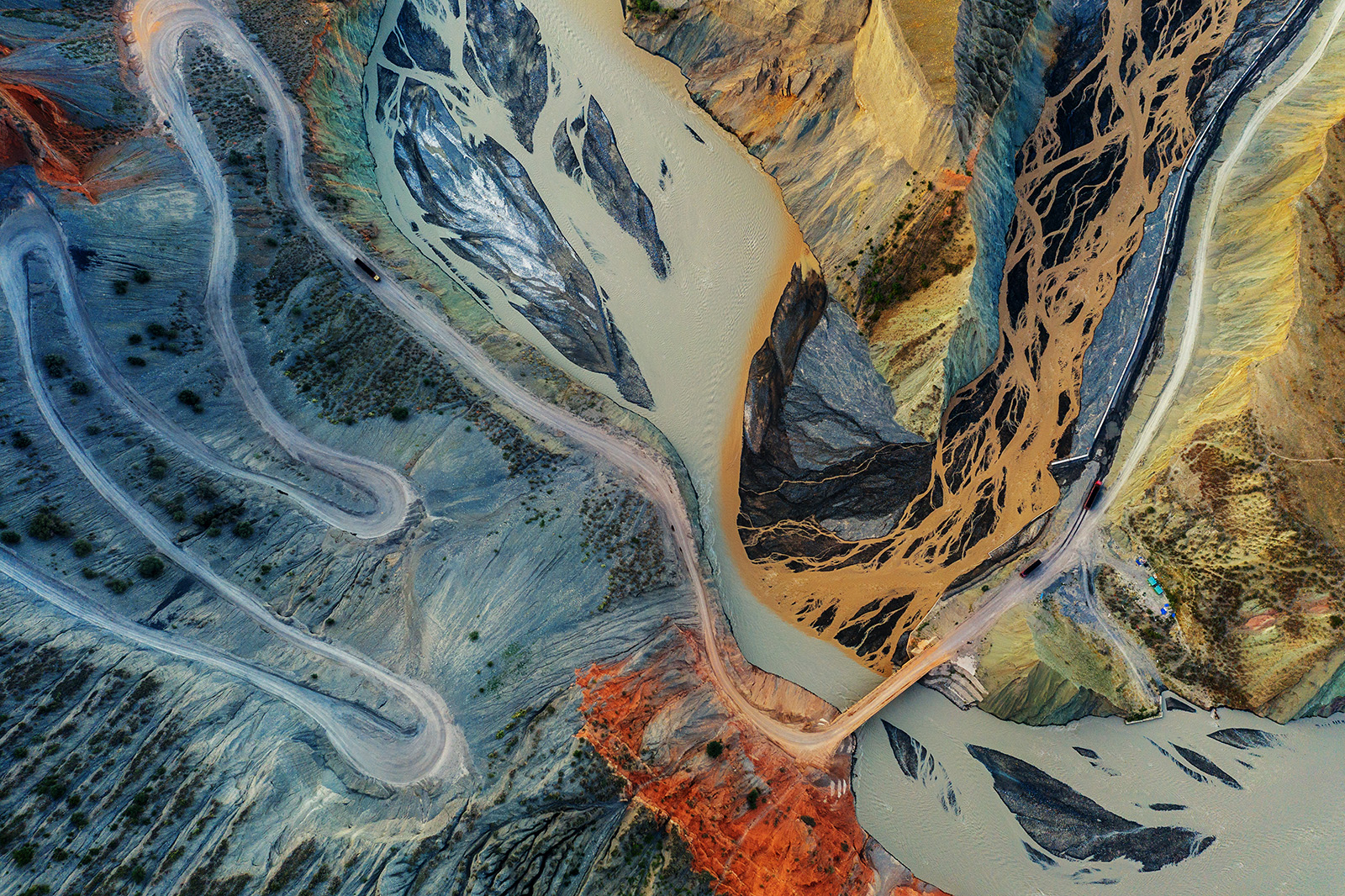

A mining truck drives down a winding canyon road in Xinjiang, China. As demand for rare earth elements increases rapidly, China aims to become the dominant producer and refiner of rare earth elements.

Photo: Getty Images

China is making an unrelenting effort to integrate and upgrade its rare earth supply chain of upstream mining, processing, manufacturing, and deeper applications. Although it has only about one-third of the world’s rare earth reserves, China now accounts for 60% of global rare earth mined production, 85% of rare earth processing capacity, and over 90% of high-strength rare earth permanent magnets manufactured.

In short, China aims to transform itself from the largest producer and refiner of rare earth elements to being the world’s major high value-add manufacturer of the clean energy products dependent on rare earth metals and other critical minerals.

The Key Ingredient of the New Economy

Rare earth elements form an integral part of the modern global economy. Rare earth elements play a critical role in developing new industries such as wind power generation, fuel cells, hydrogen storage and rechargeable batteries, as well as the permanent magnets used in electric and hybrid-electric vehicles.

They are also used as phosphors in many consumer displays and lighting systems and are vital for many defense technologies, including precision-guided munitions, targeting lasers, communications systems, airframes and aerospace engines, radar systems, optical equipment, sonar, and electronic counter measures.

Of the 17 rare earth elements, neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium are especially in demand, given their use in permanent magnets for electric vehicles and wind turbines.

Demand for rare earth elements has been increasing rapidly in recent years. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the global output of rare earth elements in 2021 was about 280,000 metric tons, more than doubling the global output five years ago in 2016, and was five times the amount produced thirty years ago. From 1994 to 2008, China’s share of the global output rose from 47% to 97%.

Though available abundantly, rare earth elements often are not found in high concentration. And they are usually found mixed together with one another or with radioactive elements such as uranium and thorium. The chemical properties of rare earth elements are such that it can be difficult to separate them from surrounding materials, and from one another, and also difficult to purify.

The process of mining, separating and purifying rare earth elements is not only highly labor intensive but can also, if not managed well, have adverse health effects and cause lasting degradations to the natural environment. Current production methods require a lot of ore and generate a great deal of harmful waste to extract just small amounts of rare earth metals. Waste from the processing methods include radioactive water, toxic fluorine, and acids.

Disorderly Development

Behind the headline of China becoming the dominant player in the global rare earth market was that the domestic industry was plagued with disorderly development and poor management. Persistent issues of smuggling and illegal mining activities, environmental damage due to poor mining practice, and the growing challenge of ensuring its own domestic needs of rare earth run against the central government’s policy perspective that “rare earths are strategic non-renewable resources.”

With the latest consolidation, the entire rare earth industry in China is now under two mega-conglomerates, one in the north and the other in the south.

The government introduced a series of measures to overcome these problems. Unfortunately some of the measures (e.g., export taxes and export quotas) that the Chinese government chose to deal with the domestic problems may have been too blunt, and China was challenged as violating its WTO protocols.

With the booming industry and the associated issues of low prices, illegal producers, market disorder and environmental pollution, the central government began to realize the importance of rare earth minerals, their corresponding strategic value, and the urgency of addressing these issues. In the early 1990s, China started to restrict foreign investment, especially in the upstream sector.

However, the problem of illegal mining and smuggling has persisted for many years into the second decade of the 21st century. The natural resource–rich areas generally are less developed economically compared to the east-coast provinces. Economic growth is still the first priority of local governments, even when the policymakers in Beijing considered policy transformation. In 2012, the city of Ganzhou in Jiangxi province needed $5.8 billion solely for land reclamation, not to mention health costs and other environmental pollution.

Industrial Consolidation

Late last year, three of the previous six companies were merged to form the China Rare Earth Group Co., an industrial conglomerate that holds almost 70% of China’s annual heavy rare earth production quota. With the latest consolidation, the entire rare earth industry in China (especially upstream and midstream) is now under two mega-conglomerates, one in the north and the other in the south.

Industrial consolidation serves multiple objectives. First, this is part of China’s efforts to boost cost competitiveness, increase production efficiency, and strengthen its grip over pricing. Second, it is seen as a way to curtail illegal rare earths exports and an opportunity to implement and enforce better environmental standards for the industry.

Third, with consolidation, China is also empowering these large conglomerates to go global. The latter is important as China faces the increasing need to import rare earths products for feeding mid- and down-stream sectors.

As a further measure, the central government has arranged to include two R&D companies in the new consolidated group to strengthen the power of domestic innovation in the rare earth industry. Innovation and technological advancements will define the future product and process innovations of China’s rare earth industry.

As of now, China is able to produce only about half of the high-performance magnets that go into EVs and wind turbines. Japan and Germany account for the remaining high-performance magnets, with Japan’s Hitachi Metals owning most of the patents for advanced sintered NdFeB magnets. But these figures are likely to change.