The Next California

Flames from the Thomas Fire burn towards agricultural greenhouses in Carpinteria, California, December 2017. The Golden State is expected to become hotter and drier over time.

ROBYN BECK/AFP/Getty Images)

As the climate changes, food production frontiers are shifting around the world. What is possible—and profitable—to grow in one place today may not be tomorrow.

Anecdotal evidence of this is popping up everywhere, but one place to watch in particular is California, which is pivotal in the U.S. food system. Until last winter, it was suffering from record-breaking drought, during which time farmers fallowed hundreds of thousands of productive acres across the Central Valley, shifted crops in others and implemented more efficient irrigation systems throughout. Though heavy snows broke the drought in 2017, the Golden State is expected to become hotter and drier over time.

This is bad news for farmers as well as America’s consumers and food companies, as California is the country’s leading food producer, accounting for a third of the vegetables and two-thirds of the fruits and nuts produced in the U.S.

Maintaining productivity in California’s unique economic and hydrologic environment is challenging enough, and climate change makes it all the more difficult. While America’s farmers are great adapters, this challenge requires the engagement of stakeholders across the food system, including producers, retailers, brands, food service providers, investors, lenders, and input suppliers. And the sooner we start, the less hurried we will have to be to uncover and address issues.

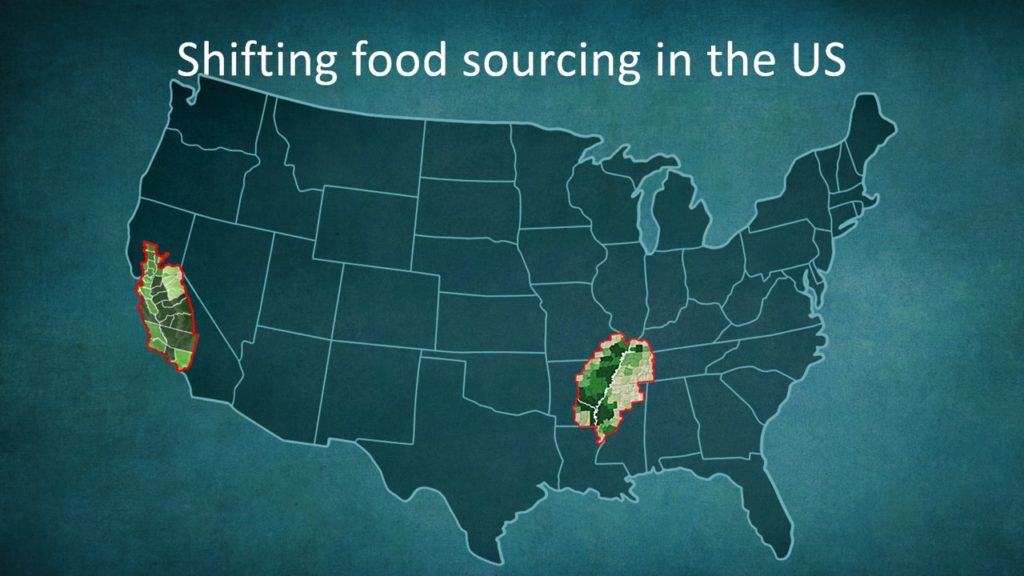

Where crops are produced in the U.S. is already shifting. As temperatures increase, Iowa—currently the country’s leading corn producer—is expected to replace the South as the center of cotton production (along with Minnesota).

As California becomes hotter and drier, over the next 10 to 20 years its specialty crops, too, will be produced somewhere else. It’s difficult to predict where, however. In the short term, California crop production may shift into northern Mexico as well as Oregon and Washington. But these locations are not ideal. So, where is the next California in the U.S. food system?

Eastward Bound

It’s important to ask these questions today, even if we don’t yet have all the answers, so that we can begin to understand the key factors that should be considered and make more informed, more timely decisions.

So, what are the conditions we should look for in new regions for specialty crop production? To start, there needs to be a similar amount of land and high-quality soil. Ideally, it’s already been cleared, so no habitat conversion would be required. The land should be no more expensive, and ideally cheaper, than comparable land in California. It’s important that the growing season is at least nine months and potentially longer with the installation of protective structures. Water must be plentiful, as well as labor and infrastructure for transportation and processing. Ideally, production would be closer to markets and would reduce food waste and overall greenhouse gas emissions along the value chain to and including the consumer.

Everyone interested in the food system of tomorrow should begin to think about how the system can respond best to the impacts of climate change.

One region that ticks these boxes is centered in eastern Arkansas and includes southern Missouri, western Tennessee, and northwest Mississippi. The Mississippi and Arkansas rivers meet in the region, providing ample water year-round. The existing agricultural area is similar in size to that of California. It has good soils, but the cost of land is only 20 percent of that of California. It has existing infrastructure—Memphis has the 10th largest installed food processing capacity of any city in the U.S.—and there is room for expansion. Walmart, headquartered in Bentonville, Arkansas, is the most significant food retailer in the U.S. The region’s central location on major waterways can significantly reduce input costs and food distribution costs and distances. Growing crops closer to the end consumers would reduce food waste—a head of lettuce that spends less time on a truck lasts longer on the shelf and in the home.

But, this exercise is not about actually picking the next California. It is about how to think about the issue. More research is needed. And, it might be better to grow specialty crops in a number of regions that are well-suited around the country rather than in a single location. Diversifying where we produce food and choosing each of the areas based on the same logic could spread the risks of production shortfalls from drought, floods, and other adverse events while reducing greenhouse gas emissions and food waste.

Preparing the Food System

Everyone interested in the food system of tomorrow should begin to think about how the system can respond best to the impacts of climate change. This is a pre-competitive issue—everyone needs to make sure that we ask and answer this question using the best thinking available. The food industry can support research and engagement that brings together academics, farmers, policymakers, business leaders, and other stakeholders to begin answering basic questions about shifting food production frontiers. Technical assistance and training programs can help farmers grow new crops, buy equipment and set up new production systems (e.g., new infrastructure, cold storage, laser-leveling), to ensure the land is engineered for optimal efficiency and productivity. Investments may be difficult to generate, but food companies can use long-term contracts to provide farmers with a tangible asset that can be used to borrow the money required for the transition. And, while there is a clean slate, it is possible to consider new business models such as producer equity schemes, joint ventures, and employee stock option plans so that producers and workers have access to the value that is added to their production and labor, respectively. This would align incentives and provide benefits to the local communities.

If we can create awareness and build consensus about the issue, we can reduce the time required to make change happen on the ground. We can also reduce the cost and make fewer false starts. Whereas waiting will produce a suboptimal outcome that will take longer to correct—if it can even be corrected. The sooner we can identify the next viable locations to produce specialty crops in the U.S., the sooner and more efficiently we can begin to anticipate the shift and ease the transition costs.