Will China See a ‘Lost Decade’?

A view of downtown Shanghai shows commercial and residential property. Similarities between Japan in 1991 and China today have raised concerns that the world’s second-largest economy may be entering a Japanese-style lost decade.

Photo: Peter Parks/AFP/Getty Images

This is the third story in a weeklong series on China.

Japan was among the world’s most dynamic economies before succumbing to one of the longest periods of stagflation. Economic growth was very robust during the late second half of the 20th century, enabling the country to overtake the U.S. in terms of gross national income by the late 1980s. The stock market climbed to record highs, housing prices soared and Japanese corporates went on a shopping spree, accumulating a wealth of assets overseas.

However, all of this came crumbling down when policymakers attempted to normalize interest rates as the yen appreciated steeply following Japan’s reluctant adoption of the Plaza Accord. The result was large asset bubble collapses in 1991 and 1992, ushering a prolonged period of stagnation and deflation known as the “lost decade.” The term originally referred to the years from 1991 to 2000, but the implications have had ramifications well beyond, haunting Japanese policymakers even today.

A Similar Story Playing Out?

Similarities between Japan in 1991 and China today have raised concerns that the world’s second-largest economy may be entering a Japanese-style lost decade. Like Japan, excess liquidity and low interest rates have bolstered equity valuations and housing prices in China. More worryingly, total debt amounts to approximately 260 percent of GDP, compared to 300 percent in Japan in 1991, led by a buildup in corporate debt (160 percent of GDP). The use of “window guidance” by the Bank of Japan played a major role in generating rapid growth and asset price inflation in the lead-in to 1991. This resembles the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC) oversight over M2 growth and interest-rate repression today. Moreover, China is facing similar headwinds on the external front; namely an increasingly antagonistic U.S. administration, preoccupied by the prospect of a hegemon in Asia-Pacific.

Despite these similarities, China in 2018 is not Japan in 1991. Chinese policymakers have a lot more say over economic levers, have internalized the lessons of Japan’s asset bubble collapse and, in many cases, consider the Plaza Accord to have been a humiliation for Japan. But notwithstanding these caveats, a series of factors are pointing toward China’s slide in the direction of a lost decade of its own.

A Slippery Slope

China is on a gradual deceleration path. This is not negative per se, as the economy is rebalancing away from its old investment-led model, toward a more sustainable paradigm centered on domestic consumption and high value-added output. The shift, however, will require growth to slow down in the short term. And yet, growth rebounded to 6.9 percent in 2017, up from 6.7 percent a year earlier. Logically, policymakers championed short-term growth over long-term reform ahead of China’s 19th National Congress in October 2017. The old drivers of growth—credit growth and fiscal stimulus—were called upon once again to achieve this goal.

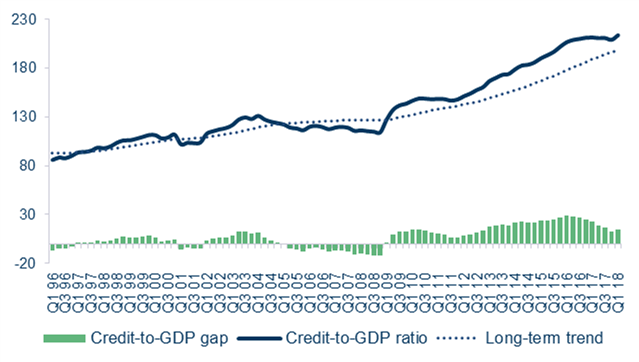

While this may have been a bonanza for the markets, the need to stimulate growth came at a cost. The set of expansionary policies put in place in 2017 spurred a widening of China’s already positive credit-to-GDP gap. A high positive gap means that the corporate sector borrows at levels that are not justified by the current output-producing abilities of the economy.

In other words, each marginal unit of additional credit generates a diminishing marginal increase in output. This is due to the fact that a lot of this capital has been allocated to less productive sectors of the economy. Most notably, lending has gone to heavy industries where zombie state-owned enterprises are rife. China’s debt is therefore leading to an accumulation of nonperforming assets and wastage. SOEs are able to use increasing levels of debt to roll over existing debt, strangling credit to productive sectors of the economy and lowering potential growth.

Exhibit: China’s Credit-to-GDP Ratio Remains above Its Long-Term Trend

The Worst Is Yet To Come

Policymakers are cognizant of the risks associated with high debt and capital misallocation. Starting in the first half of 2018, China attempted to tackle some of these imbalances by nudging the corporate sector to deleverage. They achieved this by reducing aggregate financing in the system. In tandem, regulators also urged banks to move the financial needs of the corporate sector onto their balance sheets for macroprudential reasons.

Moreover, local governments have intervened in their respective housing markets to curb speculation in real estate. The strategy worked: Leveraging of SOEs decreased while housing prices remained stable. However, the move also led to slower growth. Some observers have been quick to blame the decline in activity on the ongoing “trade war” between the U.S. and China. However, this may not be entirely accurate.

While the trade war may have had an impact through weakened investor sentiment, the impact via trade channels has yet to fully materialize. Exports expanded by 15 percent year over year in USD terms in October, reflecting front-loading ahead of the full implementation of trade tariffs in October. This is because contracts are sticky, and it may take several months before U.S. buyers are able to shift demand to a different supplier.

In addition, there may still be room for additional front-loading as the U.S. administration has threatened to impose 25 percent tariffs on all of China’s exports to the U.S. starting in January. That being said, front-loading is expected to phase out gradually over the coming months, adding to existing headwinds to growth. In fact, export momentum slowed to 0.5 percent on a three-month moving average (3 mma) sequential basis, consistent with softening global trade. Meanwhile, imports slowed even faster than exports on a sequential basis, declining by -0.6 percent month over month, 3 mma, consistent with deteriorating domestic activity.

Hard Choices

According to our calculations, trade tariffs could cost China up to 1 percent of its GDP in 2019. The impact is not negligible, especially given that the economic slowdown has not yet fully factored-in the impact of the ongoing trade war with the U.S. China has overarching growth targets, which will inevitably warrant a policy response in order to meet these goals. In fact, the PBOC has already lowered reserve requirement ratios by 250 basis points since the beginning of the year, injecting approximately $200 billion into the banking system.

Moreover, despite the bank maintaining that its policy stance is neutral, it has allowed interbank rates to fall to pre-2017 levels, facilitating credit expansion and backtracking on financial liberalization. External headwinds are inconvenient because they have caused policymakers to champion short-term growth over long-term reforms. China still has room to deploy the old growth levers. However, inefficiencies will become larger, resulting in much lower potential growth for future years to come.