As Northern Regions Warm, Will Asian Grasslands Heat Up?

Russian farmers bring in the harvest with their combine harvesters on a wheat field. We are already seeing trade agreements and investments throughout central Asia to give China access to other, new food-producing areas. So, when the thaw comes and the Russian Far East beckons Chinese farmers, what will Russian leaders do?

Photo: Daniel Semyonov/AFP/Getty Images

No one knows what the impacts of climate change will be on the global food system. The problem isn’t for lack of models and projections, or anecdotal evidence and speculation. But, simply put, we do not know how, when, or precisely where climate change will affect the global food system. For some regions, that doesn’t just mean climatic uncertainty, but also social, political, and economic uncertainty, potentially on a scale we’ve never seen.

Scientists have shown how changing weather patterns will make some areas better or worse for agriculture and how suitability will shift over time. In general, most research predicts that climate change will hamper overall productivity in the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere, while temperate and boreal regions will become better suited for agriculture.

The countries in the Northern Hemisphere projected to benefit most from climate change are north of today’s leading production areas. In North America, for example, the corn belt is projected to become the cotton belt and the new corn belt will shift toward the U.S. and Canadian border. According to the former governor of South Dakota, the growing season is 15 days longer than it was 15 years ago. In 2000, farmers in the central Canadian plains could produce four crops, whereas today they can produce 22. Increased productivity helps Canada export more than four million metric tons of surpluses to India alone. The same northward movement of production appears to be happening in Europe.

If climate change affects Asia as it appears to be affecting the West, then we could expect agricultural production to move northward as well. Indeed, we may already be seeing these impacts: In the past decade, soy production in the Russian Far East has reportedly tripled, though total production is still small.

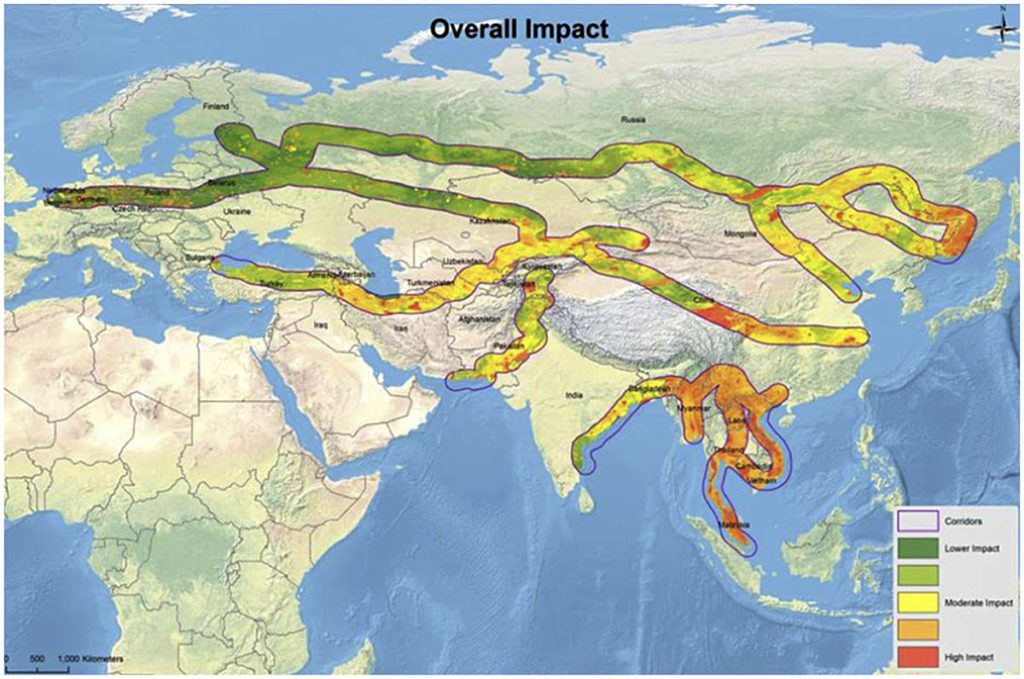

Enter China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). On the face of it, BRI (see map) is intended to strengthen infrastructure and trade in most of the Eastern Hemisphere, linking China directly to the rest of Asia and connecting to countries even farther into the Middle East, Europe and coastal Africa.

One of the key areas targeted by the northern route of the BRI is the Russian Far East, including the steppes and the boreal forests. The issue in Russia isn’t just whether the land will be increasingly suitable to produce food, but also who will be producing it and under what conditions. The Russian Far East is sparsely populated. And, since the dissolution of the USSR, populations have shifted away from rural areas and into cities.

This is where the BRI becomes even more interesting. Not only is China moving to better integrate with the rest of Asia and gain access to much needed natural resources, it is simultaneously moving 250 million people off of farms as a way to increase the scale and efficiency of production domestically. Only a third of those displaced will be integrated back as labor on these larger, more commercial farms. This means that many people with basic agricultural skills would be available to farm elsewhere. Could they move into Russia? Certainly. Would they? That’s much harder to answer. What we are beginning to see is that the movement of people is not always “official.”

Geopolitical Scramble for Agriculture

There is an old saying: When China buys rice, the world trembles. China and India will both need more food as their populations and per capita incomes increase. With climate change, it is a certainty that they will not always be able to produce all the food they need domestically. In fact, they do not do so today. But with climate change, in bad years they probably won’t be able to produce many of the basic staples year in and year out. It is then that they will depend on trade for basic food stuffs—what China now calls national security crops.

But as we have seen in Syria and parts of the Middle East and Africa, free trade doesn’t always mean that food will be available or that political systems will be stable. What we are seeing now, with only a relatively small number of people directly affected by food shortages and political conflict, is a period with record global levels of displaced people and refugees. People don’t wait for invitations to migrate.

If a similar migration begins in China or Asia more generally, even on a small scale, it could have huge impacts. What will borders mean? Especially ones that are relatively recent in the historical scheme of things. For example, the Russian Far East, even under the czars, was relatively indefensible, but at that point there weren’t many interested in the barren region. But, times and temperatures are changing, and natural resources—fertile, productive land, in particular—are becoming scarcer. Imagine what will happen if the Russian Far East becomes one of the most productive regions on the planet due to climate change.

Many view China as one of the few countries that uses science and data to plan and anticipate change. It uses its political system and five-year planning process to develop and implement its strategies. If I were a betting man, I wouldn’t bet against China being ahead of the curve once again. We are already seeing trade agreements and investments throughout central Asia to give China access to other, new food-producing areas. So, when the thaw comes and the Russian Far East beckons Chinese farmers, what will Russian leaders do?