What To Expect (and Not Expect) from India’s Elections

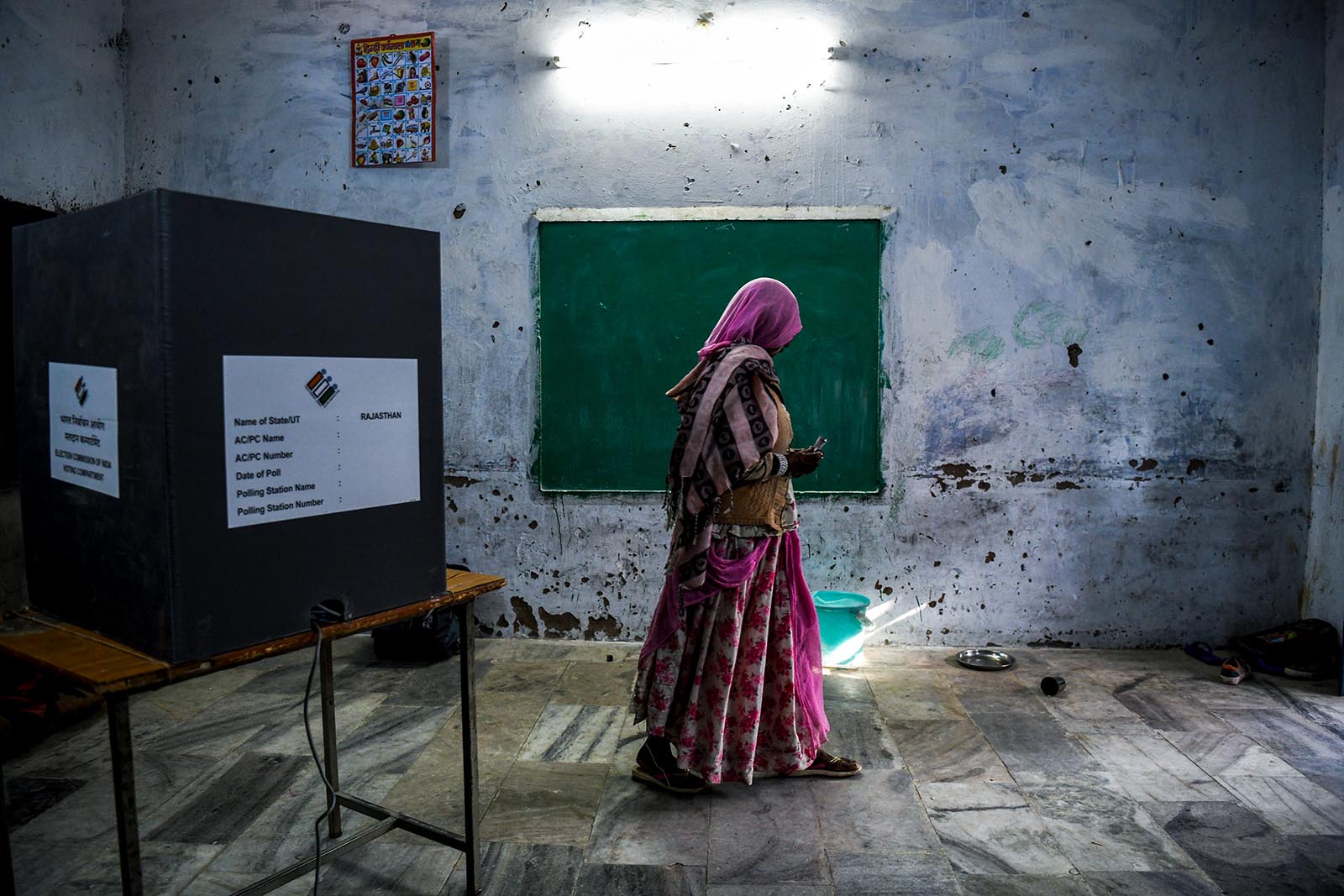

A woman leaves the poling booth after casting her vote at a local polling station in Jodhpur, India. The business community and investors are trying to understand and predict which party or coalition has the best chance to win and form the next government.

Photo: Chandan Khanna/AFP/Getty Images

This is the first of two pieces looking at the potential business impact of India’s upcoming elections. The second piece can be read here.

India, the world’s largest functional democracy, is in election mode. The country will have its general election between April 11 and May 19. Over 900 million voters are likely to use their voting rights to elect 543 members for the lower house of the Indian Parliament. Any political party or coalition of political parties that wins at least 272 seats will form the next government.

Along with the general election, India is also conducting state elections simultaneously in Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Orissa and Sikkim. These state elections are not getting much attention from the media or the business community, but they will have an impact on the composition of the upper house of the Indian Parliament.

Possible Outcomes

Along with politicians and political analysts, the business community and investors are trying to understand and predict which party or coalition has the best chance to win and form the next government. Business interests prefer the political stability and regulatory certainties that come with stable governments, so they are worried that on May 23, when the results of the parliamentary election come out, that no party will have an overall majority in parliament leading to an unstable government.

Most opinion polls seem to suggest that the Bharatiya Janata Party-led (BJP) National Democratic Alliance (NDA), led by current Prime Minister Narendra Modi, may lose over 100 seats from its tally in 2014, but will remain the top scorer and most likely form the next government, with a little help from regional parties. The Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA), fronted by Rahul Gandhi, will certainly improve its tally from last time, yet it is likely to fall short of a decent number to have any chance at government formation, despite the hype.

The problem is that opinion polls or exit polls for that matter have a mixed record in predicting outcomes of Indian elections correctly. Because of this, investors will be nervously waiting for the actual election results.

Populism’s Threat to the Economy

With competitive populism aggressively being pursued by both the mainstream parties—BJP and Congress—the question to ask is: Will India be able to meet its fiscal targets, keep inflation low and ensure macroeconomic stability?

And how will India be able to afford a new income support program for poor farmers? The opposition Congress Party wants to extend income support to all poor households (approximately 50 million households) to be paid 6,000 rupees a month ($87). That is likely to cost 3.6 trillion rupees a year ($52 billion) if they are voted to power.

Meeting Fiscal Targets?

At the close of fiscal year 2018-19, direct tax collection was 11.5 trillion rupees ($166 billion) —500 billion rupees short of the 12 trillion rupee goal, despite all kinds of maneuvers such as cajoling Public Sector Undertaking companies to pay extra taxes that could be adjusted or refunded the next fiscal year. On the other hand, because of a whopping 16 percent year on year increase in March, the overall Goods and Services Tax collection in FY 2018-19 surpassed the revised target: 11.77 trillion rupees ($170 billion) against 11.47 trillion rupees ($166 billion).

These events suggest that the federal government would be able to meet the fiscal deficit target of 3.4 percent of GDP in FY 2018-19.

Whoever comes to power after May 23 will be forced to undertake some tough measures, starting with much needed market reforms.

However, things may be difficult next year when a new government, led by either the National Democratic Alliance or the United Progressive Alliance, implements its pet populist schemes – such as income support – unless they decide to end some of them.

On the positive side, growth slowdown, especially in China and the EU, should keep crude oil prices in check. Along with that, a broader supply glut in the farm produce market should keep food inflation low. With the U.S. Fed deciding to keep interest rates unchanged, the Reserve Bank of India is likely to be accommodative. Lower interest rates, in turn, would be investment-positive.

Ever-Expanding Regulations

India’s biggest worry is an ever-expanding list of sectoral regulations, be it the fixation of floor prices (agriculture), inverted duties (textiles and electronics) or cross-subsidization (power) that will continue to frustrate businesses.

Whichever party or alliance comes into power, one can expect an extension of price control (or relatively less market distorting trade margin caps) to more sectors, not only in health care, but also for agrochemicals and seeds, for instance.

Under pressure to do something, a new government may further increase protection to industries such as steel and aluminum to aid Make-in-India and boost local jobs. That, however, doesn’t mean such policies will work. Instead, it will dampen the prospects of downstream industries, such as automobile, real estate, heavy machinery and equipment.

Unrest among Farmers

It will be interesting to see how the next government will deal with the widespread discontent among rural voters suffering from sharp correction in farm produce and cattle prices, and interstate barriers to trade in agricultural commodities leading to low price realization.

Agriculture, accounting for over half of the country’s workforce, remains the most unreformed sector, with low productivity and excessive dependence on the government. Unshackling agriculture, therefore, remains the key to improving the condition of rural India.

Much-Needed Reforms

Despite promising to double farmers’ income, the Modi government has so far avoided crucial reforms. Whoever comes to power after May 23 will be forced to undertake some tough measures, starting with much needed marketing reforms to fixing input subsidies. A likely loss in a WTO dispute over the country’s cane price support program may induce the next government to finally start agrarian reforms in the sugar sector.

Yet another expectation is reform of labor regulations. Despite creating hype, the Modi government has not done much about this in its current term either. Rationalization of labor regulations and flexibility on hiring and firing can be expected from the next government, and that’s good news.

Jobless growth and rising youth unemployment remain one of the top policy challenges for the country. Businesses must be encouraged to hire more, without being too worried about their inability to retrench excess workers.