What’s Behind the Gulf’s Trade Surge With Asia?

Abu Dhabi's crown prince, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang attend a bilateral meeting in Beijing, Monday, July 22, 2019. Much of the expected growth in GCC-Asia trade over the next decade will be powered by China.

Photo: Wong-Pool/Getty Images

The Persian Gulf has traded for centuries with Asia, but in the last decade, the volume of that trade has exploded. This is in contrast to trade slowing between the Gulf countries and the West. It’s projected that Asia will become the biggest trading partner for the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) by 2030, which could have a profound impact on world trade.

BRINK spoke to Freddie Neve, Middle East associate at Asia House and the author of a recent report, entitled The Middle East Pivot to Asia.

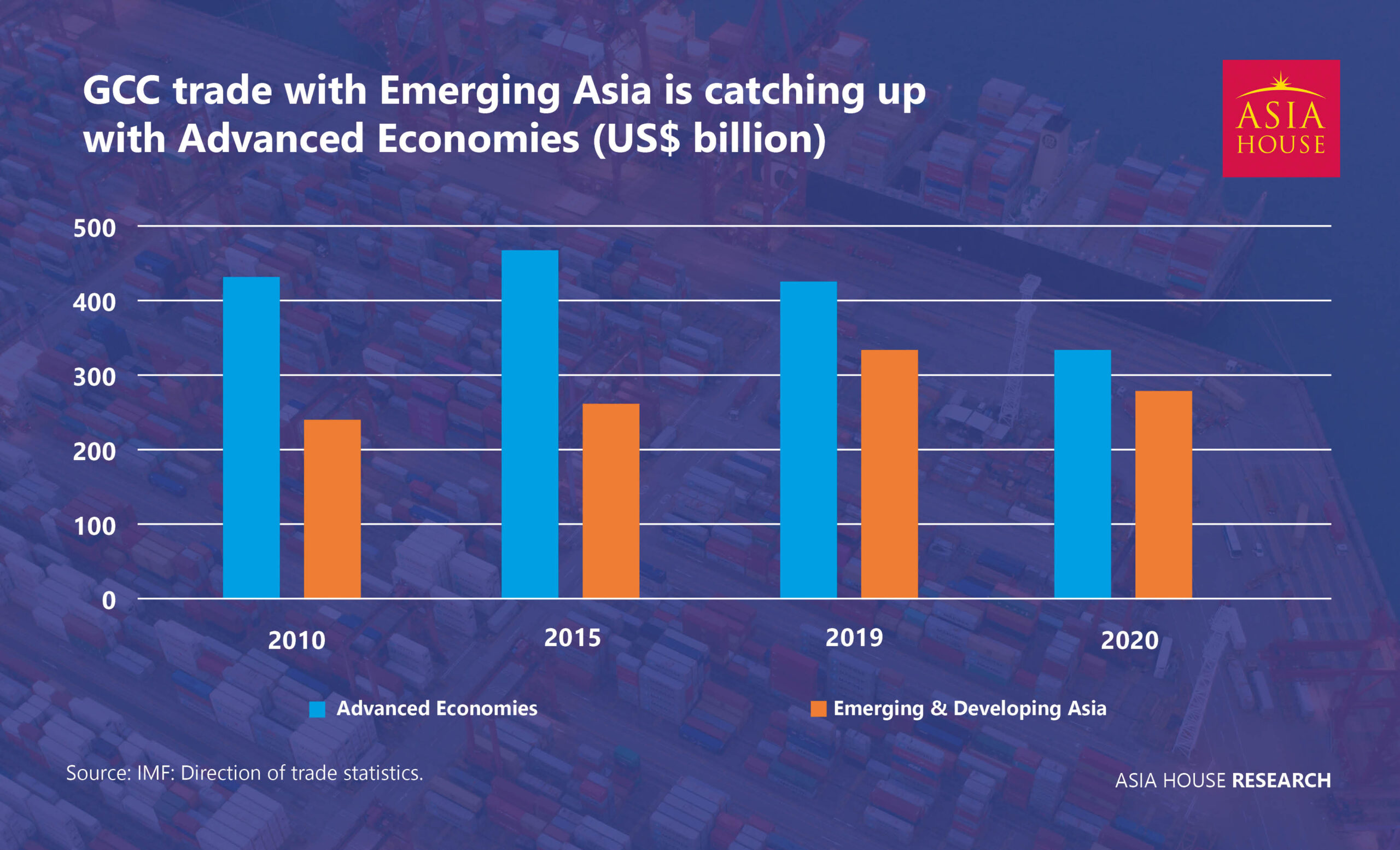

NEVE: GCC trade with emerging Asian economies, such as India and China, surged by 36% from $247 billion in 2010 to $336 billion in 2019. COVID-19 inevitably reduced trade volumes, but the outlook for further growth remains strong, and we expect GCC trade with emerging Asian economies to climb to approximately $480 billion by 2030.

There are several factors at play here. Oil has been central to GCC-Asian trade and will remain so over the next decade, with some forecasts, for example from the IEA, suggesting that Asian oil demand will not peak until 2026. Gulf economic diversification is also creating opportunities for Asian investment to flow into emerging sectors such as renewables, infrastructure and the digital economy.

There will be plenty of opportunities for businesses in both regions to capitalize, particularly as we’re also seeing increased interest from GCC sovereign wealth funds in Asian markets, with several establishing bases there.

Rising Hydrocarbon Demand

BRINK: If it is primarily Asia’s thirst for hydrocarbons, what does that tell us about Asia’s commitment to a low-carbon economy?

NEVE: 2021 has seen governments in both Asia and the GCC make new carbon emission reduction targets or enhance existing goals. There is a genuine desire from both regions to become more environmentally sustainable, but ultimately, reconfiguring economies toward a low-carbon future will take time. It depends on the speed of technological advances in renewables and alternative fuels such as hydrogen, as well as access to green finance.

For at least the next several years, we will see rising Asian demand for hydrocarbons and their associated products to satisfy their growing economies and populations. The Gulf states are diversifying their economies but remain dependent on fossil fuel exports to generate their revenue.

One very interesting trend we are seeing is increased cooperation between Asia and the GCC in green investment. The GCC is investing in renewables and developing carbon capture use and storage technologies and alternative low-carbon fuels such as “blue ammonia.” We have also seen Asian finance and expertise involved in developing some of these projects.

Building on the Belt and Road

BRINK: Are there geopolitical reasons behind this, or is it purely economic?

NEVE: I believe economic interest is the main factor, but there are some geopolitical considerations at play. For Asia, closer ties to the Gulf helps enhance its energy security. Certain Asian investments in the Gulf energy sector are particularly geostrategic, with businesses investing in ports and oil storage facilities that are not vulnerable to the closure of strategic maritime chokepoints, such as the Strait of Hormuz.

For the GCC, interest in Asia is primarily economic. Asia is their main export market and an important source of capital and expertise to deliver their economic diversification strategies, but some decision-makers will see closer ties as a way of hedging between East and West, diversifying their international partnerships, and making them more resilient.

BRINK: Does the Belt and Road Initiative play a big part in this?

NEVE: There has been significant BRI investment in the Gulf, and President Xi Jinping has previously called the Gulf states “natural partners” in delivering the BRI.

China is a major investor in the Gulf, with investment into the region rising from around $6 billion in 2011 to a pre-pandemic peak of around $15 billion in 2018. These investments have largely focused on improving infrastructure and ports in the Gulf, in turn promoting greater regional integration, economic diversification and growth. China has been involved in several key gulf projects such as Etihad Rail, Oman’s Duqm Port and Jeddah Islamic Port.

Of course, some BRI projects have encountered delays or been abandoned entirely. While the Gulf states are happy to be involved in the BRI, any instances of stalled or failed projects may reduce the Gulf’s enthusiasm.

Implications for US-China Relationship

BRINK: What are the implications for the U.S.-China relationship?

NEVE: Much of the expected growth in GCC-Asia trade over the next decade will be powered by China, increasing Beijing’s relative importance as an economic partner to the Gulf.

We have also seen increased political cooperation between the Gulf states and China over the last few years, and inevitably, as China’s economic importance to the Gulf increases, so too will its political importance.

The West remains an important security and economic partner to the Gulf, and there will be great reluctance in GCC capitals to undermine this, but we have seen instances where the U.S. has tried to press the Gulf to curtail their economic ties with China in sensitive areas such as 5G technology.

So, were U.S.-China tensions to rise further, I could envision more pressure being applied on the Gulf to reduce political cooperation and economic cooperation with China, particularly in sensitive sectors such as the digital economy, nuclear power and defense.

This is why the Middle East pivot to Asia is a key geopolitical trend to watch over the next decade.

BRINK: How is this likely to impact the EU?

NEVE: GCC trade with the euro area has grown in absolute terms over the last decade, but has declined in relative importance. But like the U.S., the Gulf will still consider the EU and U.K. to be important partners.

There is a soft power element to this as well. London, Paris and other EU capitals are big holiday destinations for Gulf citizens and considered safe destinations for money to be tied up in banks, investments or property. I believe this will remain the case for some time and is one advantage Western capitals have over those in Asia.

Trade Discrimination

BRINK: Are GCC countries likely to preference Asian companies over U.S./EU ones?

NEVE: I don’t think there will be a deliberate strategy to do so. The Gulf states are keen to diversify their economies, and a fundamental aspect of this is attracting more foreign investment and foreign businesses onto their shores.

While we have occasionally seen Gulf states erect market and trade barriers for political means, such as during the 2017-2021 dispute between Saudi Arabia, the UAE and others with Qatar, deliberate discrimination between large markets like Asia and the West would be very counterproductive. Unless there is an unexpected rupture between the Gulf and the West, I don’t foresee it happening.

So, for the most part, any inclination toward Asian firms over U.S./EU firms will be dictated by market forces. As we see more Asian companies establish themselves in the GCC over the next decade, inevitably there will be greater competition between them and Western firms for state contracts.

BRINK: GCC countries are experiencing big demographic changes — how will this trend impact these changes?

These trends will only mean good things for the GCC’s trade with Asia. The projected populations of the GCC’s biggest economies, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are expected to swell by approximately a third between 2016 and 2030, according to research by the International Labour Organization.

This should increase demand for Asian goods and have a positive impact on economic growth in the GCC, which in turn will present opportunities for Asian businesses.

Meanwhile, the GCC’s investment in the non-oil economy, such as the digital economy, infrastructure, entertainment, renewables, mega-projects and so on, is creating new opportunities for Asian firms to offer their expertise and services.